Seaside resorts in decline

In the 1920s, a new type of tourist emerged in Brittany. They were less well-off, but also more sports-oriented and curious about the area. Many writers and painters would holiday there with their families, taking advantage of the cheap hotel prices and a landscape that was still largely untouched. The price of land and houses meant that a large number of those who wished to return often to the area could afford to buy a second home there.

Dinard, which had always reigned supreme as the number-one seaside resort, suffered a setback when its mainly British clientele were forced to return home thanks to UK regulations which limited trade and spending abroad. Several large building projects were hit hard, and only the most prudent and modest investors were rewarded, for example in Concarneau, Tréboul and Paramé.

After the Great War, La Baule Baule remained an exemplary model, since the developers’ projects were consistent with and backed up by solid financial support.

The failure of the Sables-d’Or-les-Pins resort established by Roland Brouard (1887-1934) in Pléhérel (known today as Fréhel) was the most significant. Hundreds of immigrant workers were hired between 1922 and 1924 to level the land, complete the first stage of construction, and create five and a half miles of road within the 90 hectares of woods and sand dunes. The project’s developers wanted a piece of the growing automobile industry. They had the unwavering support of La Bretagne touristique magazine. From 1927, the resort had its own casino and a large restaurant, sixty villas of varying styles, and more than 1,000 rooms available to holidaymakers. But the Wall Street Crash of October 25th 1929 stopped Roland Brouard’s dreams in their tracks, as well as those of his friends, who didn’t have enough capital to see out the crisis. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 1950s that the resort made a comeback thanks to the positive economic turn, although during the winter it still resembled a windswept ghost town.

The beginnings of mainstream tourism

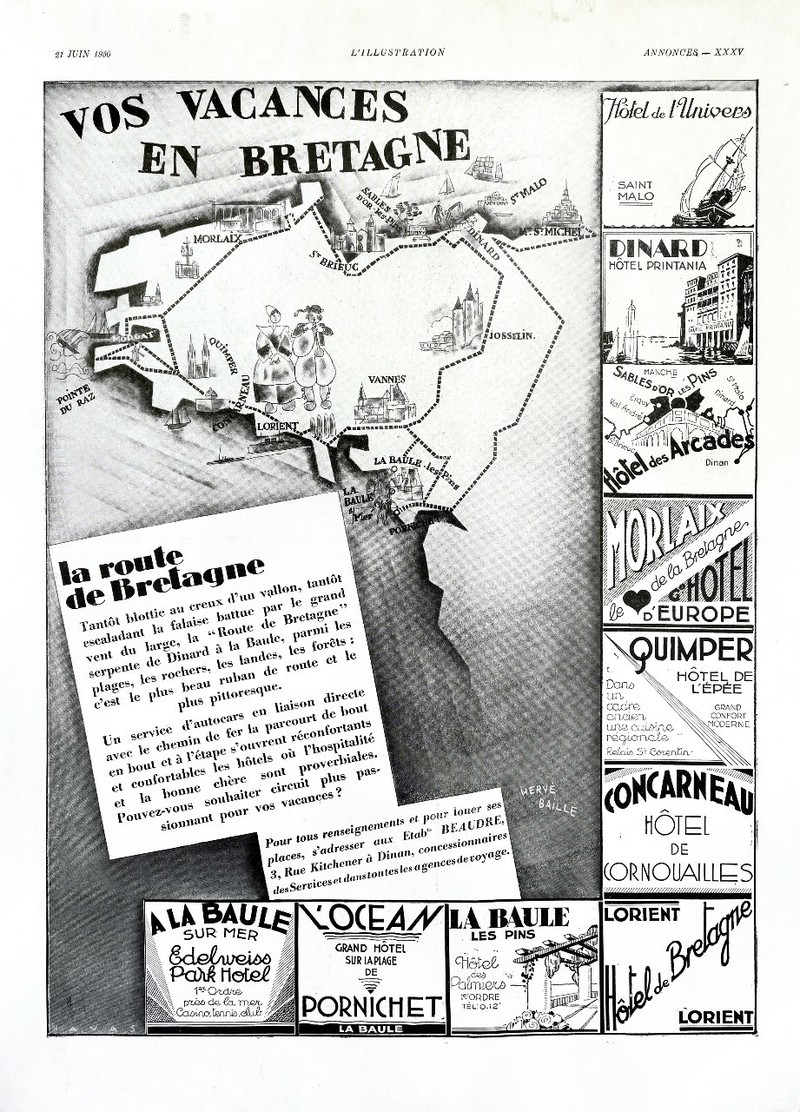

From 1853 onwards, civil servants were granted 15 days a year paid leave. Certain professions also managed to gain paid holidays as the years went by, and what was known in France as the ‘semaine anglaise’ (a five-day work week) resulted in important progress being made at the start of the 20th century. But it was in 1936 when all employees were granted paid holidays that things really changed.

Summer '36: home-made holidays

These new regulations were in fact put in place too late, and employees were not in the habit of spending their leisure time travelling long distances, discovering new places or renting holiday homes. Those who did travel tended to visit family members who had enough space to accommodate them. Of the 600,000 reduced-price tickets bought that summer, many of them were used for such family visits. It’s important to remember that at the time, half the population were farmers and the only holidays they knew were those taken by other people. In fact, “there is no Breton word for ‘holiday’, except for a term used specifically for school holidays”, wrote PJ Hélias.

There were therefore no great crowds rushing to the beaches. If it seemed that way, it was simply because there wasn’t enough accommodation available for the small numbers that did go, rather than because of any genuinely massive influx. These people were a new kind of clientele who lived in nearby towns and cities and who could therefore sporadically take advantage of the good weather to visit the coast, resulting in the ‘congestion’ described in an article in the magazine Bretagne, written by the Deputy Mayor of Pouldreuzic, Albert Le Bail. “This year, paid leave has literally taken over the area. Every available room in the town has been requisitioned by desperate hoteliers, who have had to refuse between twenty and thirty guests per day. Nearby, the up-until-now anonymous little port village of Lesconil has had to provide accommodation for more than 1500 bathers, a number easily exceeding that of its usual population. The visitors slept in cellars, attics and dormitories.”

The glorious 1950s

Once the war was over, dreams of holidays became a reality for many Bretons, even if they were only long enough for a family trip to the nearest beach on a Sunday.

Holidays took on a feeling of freedom. People parked their cars right on the beach, camped almost anywhere, either on deserted municipal land, or in fields generously lent by the many and welcoming farmers living in the area. Family guest houses were a very reasonably-priced alternative and, for those who found it hard to say goodbye, with a small inheritance it was still possible to buy a parcel of land or a ‘doer-upper’ without falling into financial ruin. Gradually, cabins and caravans were set up long-term and it was fairly easy to establish a friendly relationship with locals. One could almost believe that slowly but surely the ‘Trente Glorieuses’ (post-war period between 1945 and 1975) had established the utopia devised two centuries earlier: Brittany was becoming a welcoming and pleasurable holiday destination for all.

The long school holidays played a huge role in the way people chose to spread out their paid leave. Not only did they mean teachers swelled the ranks of tourists over that period, but they also encouraged mothers who did not work to take long trips to the coast, since between 1912 and 1983 the summer holidays lasted a glorious 10 weeks!

The end of an era

Looking at the changing perspectives of the last two centuries, it's clear to see that the population's attitude towards the seaside has changed enormously. In France, as well as other countries, people gradually rid themselves of the paraphernalia of rolling booths, therapeutic rehabilitation and bathing gowns, not to mention their fear of water. A 'health visit' to the marine baths became a holiday, with everything that entailed in terms of breaking away the usual rituals of everyday life, instead inventing new ones. New traditions were born, combining Brittany, the original paradise, with a host of innovative activities (sailing, camping, postcard-writing…).

Brittany’s holiday ‘belle epoque’ lasted 150 years. The first English tourists arrived in 1815, and the year 1965 is seen symbolically as the beginning of mass tourism, with the launch of a huge marina and pleasure beach construction project, the port du Crouesty on the Arzon peninsula. New holiday traditions took off and slowly but surely, holidays in Brittany became part of the cultural fabric of France.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill