Bretagne cloth at the forefront of textile production

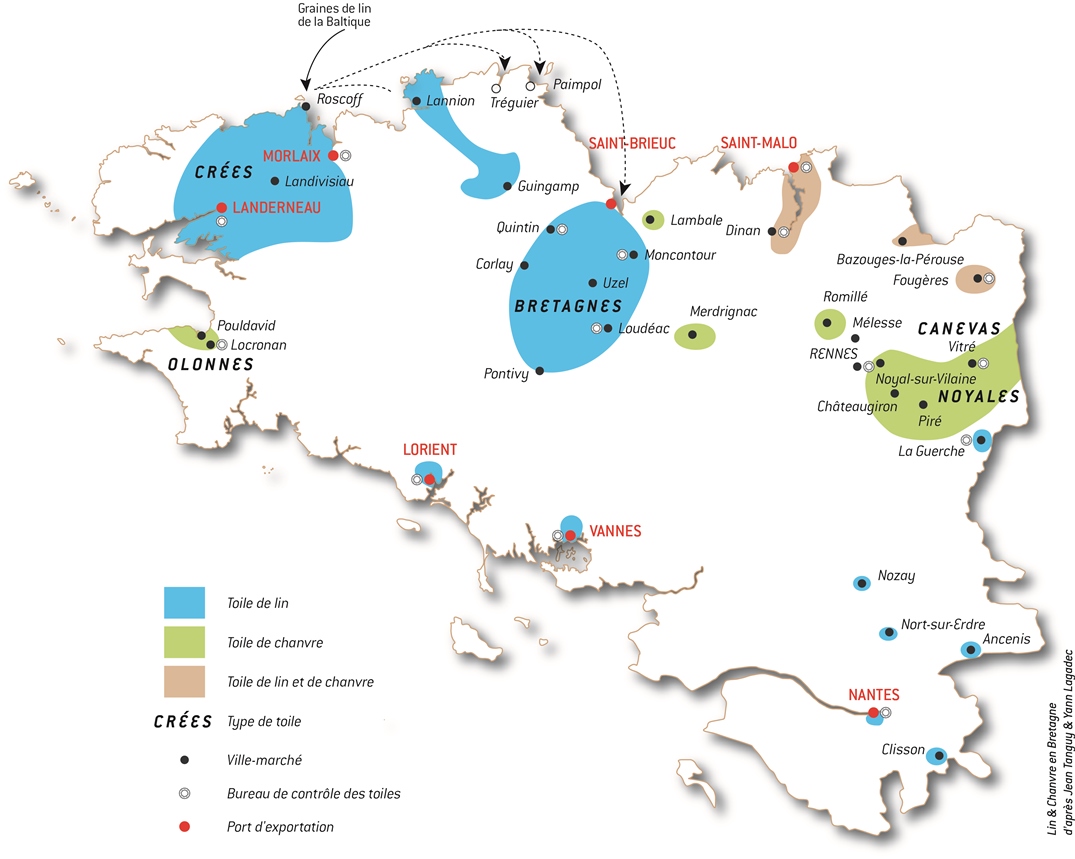

In 1686, in a famous memoir written by Seignelay, Navy Secretary appointed by Louis XIV, General Commissioner Patoulet who had been sent to Cadiz via Saint-Malo stated that “Bretagne cloth was greatly admired by the Spanish” who “consume great quantities of it”, creating approximately 4.75 million livres tournois in revenue, twice as much as crée cloth, the linen fabric woven in Léon, and ten times more than cloth from Fougères. On a national scale, only the cloth woven in Rouen was comparable to what Patoulet called “the cloth of Quintin and Pontivis”. Of course, Spain wasn’t the only market to which Brittany exported. Other markets included the British Isles - although this started to become less frequent - the United Provinces of the Netherlands, the Spanish Netherlands, the West Indies and France’s American colonies. Nevertheless, Seignelay’s memoirs reveal the introduction of a new hierarchy in Breton produce. Crée cloth had dominated the market during the 16th and 17th centuries, helping to build Léon’s famous parish closes, but the closure of the British market at the start of the 1670s paved the way for bretagne cloth to take centre stage during the 18th century.

Four Principal Markets

Production was organised around four market towns, where weavers and merchants traded yarns and cloth. From the 18th century onwards, the cloth was also branded. Quintin was the biggest of the four market towns, not least because it was the oldest. 83 merchants traded there in the 1780s, and a further 25 were regular visitors. But the markets of Uzel, Montcontour and especially Loudéac (194 merchants around the same time, 40 of which came from this one small town) slowly began to grow, even if the most influential traders resided in Quintin. From these four towns, the rolls of cloth were transported by road to ports for export. To Nantes for most of the 16th century, then mainly Saint-Malo, Morlaix to a much lesser extent, and very exceptionally Saint-Brieuc. The latter’s Légué port never really reaped the benefits of its geographical proximity to the production zone.

The State’s double organisational role in manufacturing

The bretagne cloth trade was concentrated within these four markets because of the State’s Colbertine need to control product quality. Thanks to regulations put in place mainly in 1636 and 1736, the bretagne cloth production area became a designated manufacturing zone in which makers had to respect very strict rules concerning the cloth’s size, number of threads in a chain, weft, etc. In this way the State and its product inspectors could guarantee foreign buyers cloth of an - almost - flawless quality. It was this guarantee, amongst others, which ensured the success of the export of this type of cloth, bringing relative prosperity to the area in which bretagne cloth was produced.

Throughout the 18th century there was regular backlash against the excessive levels of control and the zealousness of certain inspectors. However, having first riled against the regulations, some traders then complained about the deregulation that took place after the easing of trade restrictions post 1790-1791, which helped lead to the decline of the designated manufacturing zone. Without its quality guarantee, Brittany’s cloth couldn’t compete with fabrics coming from elsewhere, such as Silesia (Prussian province), which were also cheaper.

Political and Economic Double Impact

Due especially to its dependence on the Spanish market, the production of bretagne cloth was influenced by two separate contexts. Firstly, the quality of its relationship with the Spanish and its capacity to trade with Cadiz. Every new conflict with the Spanish monarchy, but also with England due to the Navy’s near-total domination of the seas, could hinder or even suspend exports from Saint-Malo or Nantes. In addition to the effects of this international diplomatic situation was the economic context. The increase in competition from Silesian cloth at the end of the 18th century and the repeated demographic and economic crises of the 1740s weakened the market more or less permanently.

The lack of access to foreign markets during the Revolution as well as internal problems that arose from the Chouan Rebellion deeply affected production stability and any hope for a return to the pre-1789 context fizzled out. Attempts to win over the French market, as well as technical improvements like the introduction of the flying shuttle from 1806, or the Jacquard loom in Quintin in the 1840s did nothing to prevent the irreversible decline of the bretagne cloth production zone in the first half of the 19th century.

Although some weavers were still working around Quintin and Loudéac between 1850 and 1870, the business was a shadow of its former self. Emigration numbers from the 1830s are proof enough that this small area of activity was no longer. And the fate of Joseph Léauté's 1870s Uzel weaving business, taken over by Mr. Planeix in the 1930s, only serves to reinforce the depth of the crisis experienced by the once-prosperous bretagne cloth production zone.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill