Before the war, the Bretons’ attitude towards the institution represented by military service was one of conformity. The law decreeing three years of compulsory military service in 1913 had not been a disputed issue. The principal concern in the agricultural sectors was seeing the young men changed upon their return after having accustomed themselves to the comforts of the city and that this in turn would lead them to question the rustic way of life and work on family farms and even leave them definitively.

A menacing horizon

In July 1914, the great majority of the Bretons’ attention centred on the harvest which rain could occasionally ruin. Newspaper readers were captivated by the Caillaux trial rather than the attack in the Balkans which seemed considerably less serious than the crisis concerning Morocco that had turned France against Germany in 1911.

The journey to Russia made by Poincaré, the French President and Viviani, the President of the Council reinforced the idea that the threat of war was unlikely.

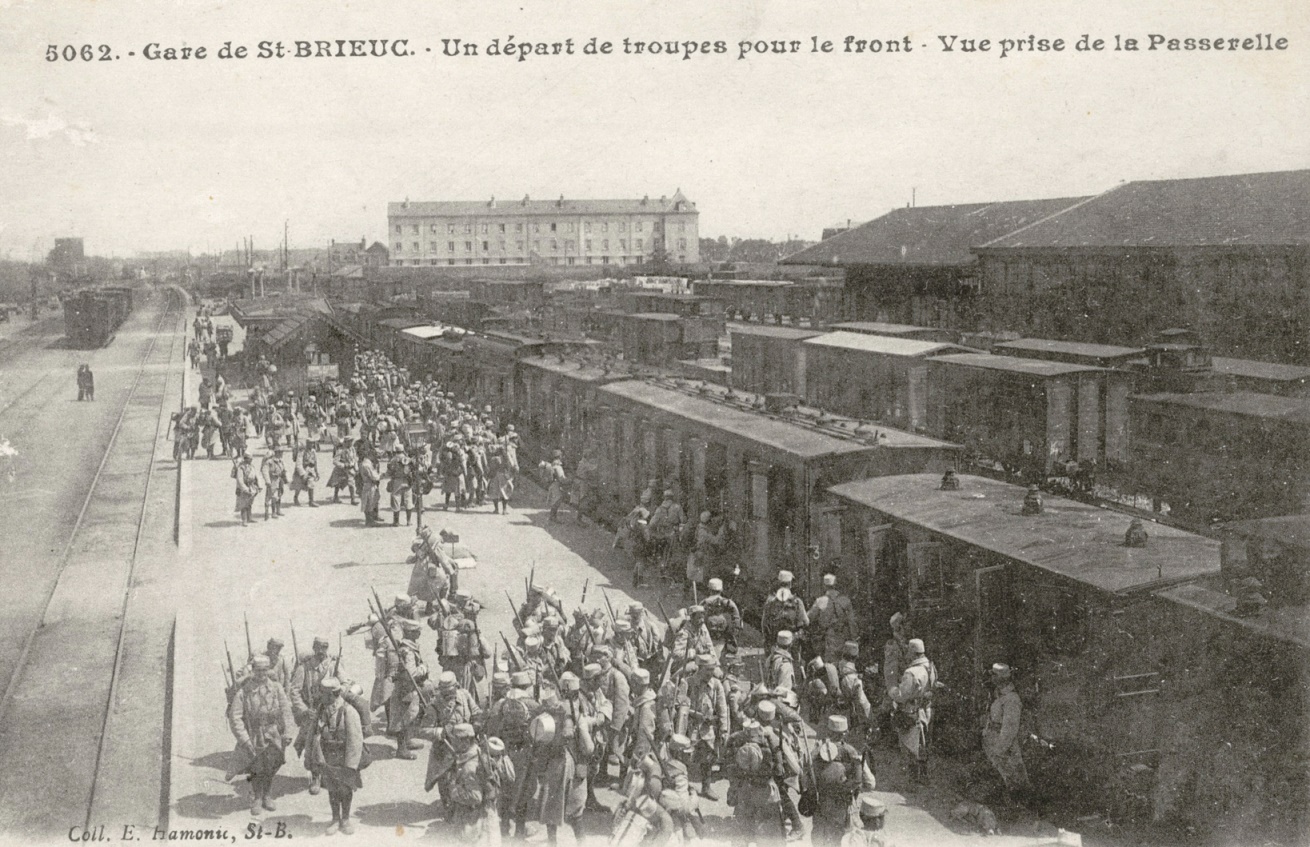

The first apprehensions appeared in the press on July 26th after Serbia responded negatively to the ultimatum given by Austria-Hungary. L’Ouest-Eclair thus ran “Europe on the brink of a conflagration” as a headline and announced Viviani’s imminent return to Paris.

Waning pacifism

In the trade unionist and socialist sectors, this march to war sparked important pacific protests in Paris on July 27th and their equivalents in Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire and Nantes between July 27th and 31st. The assassination of Jaurès (a socialist politician, killed because of his pacifism and aversion to the First World War) on the 31st by a French nationalist, did not lead to havoc but rather to a patriotic movement which overtook the workers’ sense of pacifism. The movement can be summarised by Gustave Hervé’s famous phrase, “they have assassinated Jaurès, France will not be assassinated.”

In Brittany, similarly to other places, the authorities did not arrest leading figures, recorded in the Carnet B, that were likely to lead pacific actions that would impede the call to arms at the beginning of the war. These arrests were rendered useless by l’Union Sacrée and could have, ironically, ignited a contestation that did not exist.

The Church in the Union Sacrée

Similarly, the Catholic Church in France decided to support the government and joined the Union Sacrée, despite the government’s anticlerical policies which culminated with the 1905 law decreeing the separation of Church and State. The enforcement of this law and the stock-taking of the Church had provoked incidents in France, particularly in Brittany where a number of stock-takings had not taken place due to the opposition of the clergy and the parishioners.

However, if the Church was to support the State in the face of a German threat, it asked that the Republic at least revised its policies and recognized that it had been unjust.

This patriotic conviction was best exemplified with the departure of Priests to the Battle Front because they were subject to military obligations since 1889. They were named les curés sac au dos (the backpack monks). For instance, in the diocese of Vannes, 625 Priests were called up. The youngest were enlisted as soldiers whilst the older ones were assigned to medical work.

Additionally, a law passed in 1913 anticipated the presence of military chaplains and from November 1914 onwards the State took responsibility for the compensation assigned to the voluntary Chaplains on the Battle Front. Thus, in Brittany, like in the rest of France, Church and State became closer whilst confronted with the peril of war and the latter even organized a Catholic apostolate for the troops.

Motherlands- small and big countries together

What can one say about a Breton nationalist movement refusing to participate in another nation’s war? The first Breton nationalist Party was founded in 1911 but it consisted of only a tiny minority of members from the cultural elite and was consequently far from having the means of swaying opinions. The Bretons’ sense of identity was still anchored in the sense of belonging to a small rural community. Brittany’s unity was therefore fragmented into multiple entities which had their own sense of identity such as the Vannetais, the Léon and the Pays Bigouden. Alongside this diversity of communities, there also existed a divide between Upper and Lower Brittany demonstrated by the usage of either Gallo or Breton.

United in the face of Germanic barbarism

Finally, from the adherence of the trade unionist and socialist movements as well as the Church to the Union Sacrée, to the feebleness of nationalist sentiment: everything contributed to the fact that Brittany did not differentiate itself from other French regions during the entry to war. The Union Sacrée was established in the face of an imperialist Germanic threat.

Brittany did not experience more cases of insubordination amongst those that were called up than anywhere else and the soldiers departed with the belief that they were accomplishing their duty. They exuded the patriotism instilled by the government and its institutions. The military service and state schools exalted love for the French nation: the beacon of civilization which had to be protected and defended. The Church contributed to this patriotic movement as is demonstrated by the soldiers’ prayers addressed to the Virgin Mary and which finished with “Vive la France” (“Long live France”).

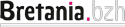

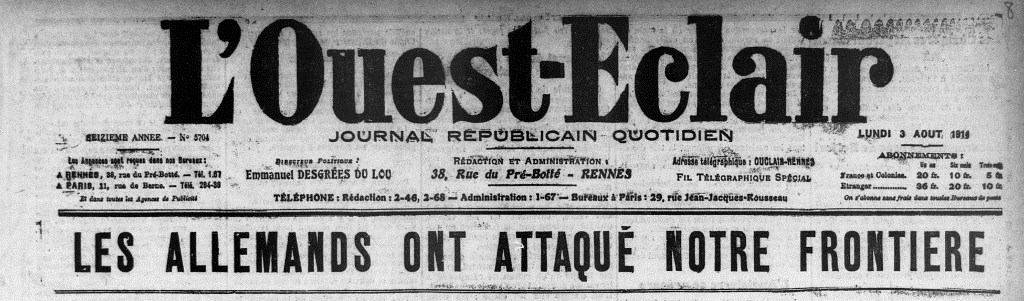

592 000 men from within the frontiers of the ancient province, (the province of Brittany including the Loire-Atlantique) were called to arms, of which 50 000 were assigned to the navy. The myth of the soldiers leaving light-heartedly and without a care in the world bears as little resemblance to reality in Brittany as it does in other regions. It was rather the feeling of inevitability and determination which drove civilians and soldiers forward during the departure to a war which, they convinced themselves, would be short.

![Eñvorennoù daou soudard ar brezel 14-18 [Témoignage de deux anciens poilus]](http://fresques.ina.fr/ouest-en-memoire/media/imagette/512x384/Region00543?#)