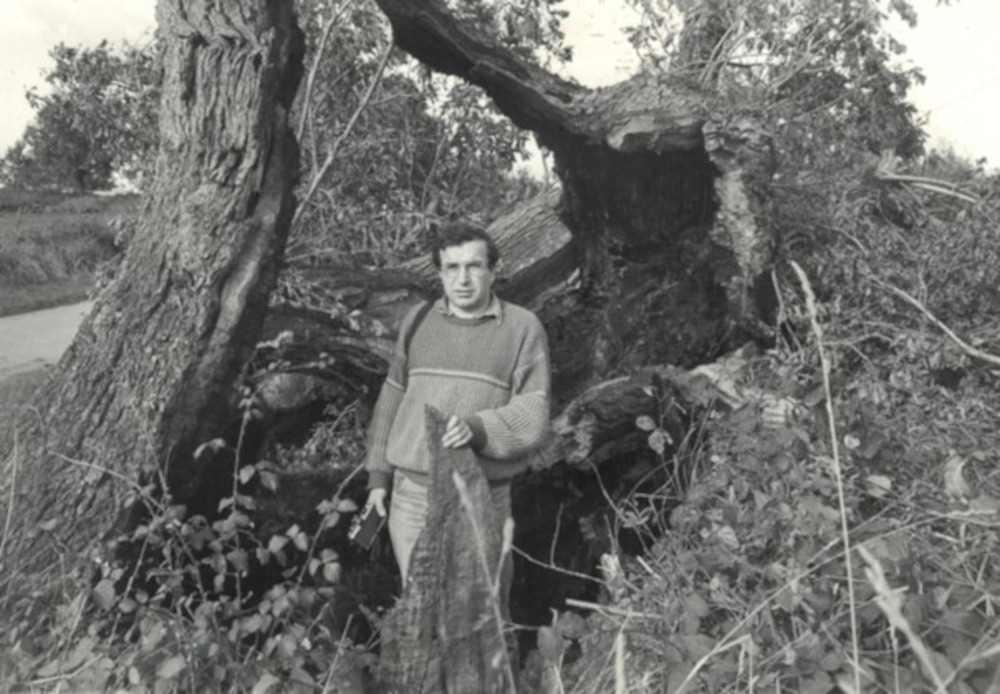

Gilles Morin (1951-1999) was the central figure of the Gallo movement between the end of the 1970s and the end of the 1980s. He came from a modest background (his father was a road worker and his mother was a cleaner) and he grew up in Trégomar, near Lamballe. He was a bright and able pupil, and he went on to study in Rennes where he received his agrégation in history in 1975 at the age of 23. He then became a secondary school teacher.

As a young man, he quickly became involved with the Amis du parler gallo, at the time a small academic society, and he became its president in 1978. The following year, he helped launch the Assemblées gallèses festival and the Lian review Most importantly, as a firmly entrenched member of the alternative community post-France’s civil unrest of 1968, he lent a tone of resistance to the re-emerging Gallo movement, offering it a powerful social dimension, as well as new theoretical founding principles. The first major evolution was a rejection of the term ‘patois’ in favour of the more esteemed qualifier ‘language’. He also helped to the movement find its place as part of Brittany’s cultural and political struggles. In 1984, the society adopted the name Bertaèyn Galeizz, an expression of severe criticism towards Emsav which was accused of marginalising the Gallo movement. According to Morin, Gallo was suffering from a form of ‘double satellitization’, in reference to French sociolinguist Jean-Baptiste Marcellesi’s concept of ‘satellitization’, which was ‘the phenomenon by which a dominant ideology attempts to link one language system to another, to which it is then compared and declared as a distorted or subordinate form.’ Gallo was therefore stuck between a rock and a hard place: the centralised French language system and a doctrine which sought to recreate it in the image of the Breton language.

At the start of the 1980s, together with Christian Leray with whom he shared an interest in the educational reform solutions proposed by Célestin Freinet, he met with the French Education Department to request Gallo be taught in schools. The two teachers convinced the Académie de Rennes’ education officer of the advantages of Gallo as a means by which to combat the number of pupils underperforming in rural areas. At the time, confusion between Gallo and French was indeed having a disastrous effect on the speaking and writing abilities of some pupils, as well as on their self-confidence. From the second half of the 1980s, 3,000 pupils a year were taught in Gallo. This legitimization of the language and its teaching was continued at university level via the short-lived LERG project (Laboratory for Gallo Study and Research), a research centre linked to Rennes 2 university, backed by the linguist Henriette Walter and run by Gilles Morin.

Far from concentrating just on the language, its aim was also to build connections between the pays gallo’s different cultural facets, linking them through language: dance, music, song, crafts, natural heritage sites… Many of its projects took place around Concoret in the Morbihan region, home to storyteller and poet Ernestine Lorand and where Gilles Morin bought a house in 1987. He massively contributed to the emergence of a form of Gallo counterculture in the Brocéliande area, in which an understanding of rural culture and traditions met with alternative forms of thinking.

Through his ebullient activism and powerful appeal, this extraordinary campaigner left an indelible mark on the Gallo movement, from which he then distanced himself in the 1990s. Those who knew him remember his strength of character and ebullience. He died suddenly in 1999 at the age of 47. As an activist, he left behind a founding legacy, the extent of which has been revealed by his archives. This exceptionally rich collection was kept by his family for more than 20 before being gifted to the Académie du Gallo in 2023 so that an inventory could be established and the public could have access.

Translation: Tilly O’Neill