Gallo is a regional evolution of the vulgar Latin learned from the Roman legions who came to Gaul. The word ‘Gallo’ comes from the Breton gall, meaning stranger, a person who does not speak Breton. From the 19th century, ducal deeds and other texts mention Bretaigne gallo, or Bretaigne gallot, differentiating it from Bretaigne bretonnant, and showing that the glossonymic use of the word ‘Gallo’ is not new. In particular, it is used in a document from the Coquebert de Montbret archive, preserved at the French National Library. While this civil servant was doing a survey for the First French Empire, an informer sent him information regarding 'this gobbledegook spoken in Ploermel called Gallau.' In rural areas, the word only seems to have been used in communities close to the Breton-speaking region, but from the 19th century, educated people from Paul Féval to Paul Sébillot commonly used it to describe the language spoken throughout Upper Brittany.

Gallo territory

Today, Gallo is spoken east of the linguistic border, drawing a line more or less from Saint-Brieuc in the north, down to Vannes in the south. It’s a border that has moved over time. From across the Channel, different peoples speaking Celtic languages reached the city walls of Rennes and Nantes around the 9th century. In the centuries that followed, the Breton language was constantly being pushed back westwards, in favour of Gallo-speaking territories. Some lexical, phonetic and even grammatical elements (although the latter is regularly disputed) are in fact closely linked to Breton in those areas.

The linguistic border between Gallo and Breton remains a structural part of Brittany today. Data from a 2018 survey by TMO shows that around 90% of people who speak Gallo live in the pays gallo and around 82% of Breton speakers live in Lower Brittany. The greatest numbers and proportions of Gallo speakers live in rural areas, with up to 27% living in the south-east of the Côtes-d’Armor.

Throughout Upper Brittany – and even more so in the east of the region – Gallo is similar to Oïl variants found in Maine and Anjou, and to a lesser extent to those found in Normandy and Poitou. This is no surprise. A complete linguistic break from the vast continuum of Latin languages would be extremely rare. It’s why the pays gallo is far from a linguistically homogenous zone, and one shouldn’t neglect the varied regional influences that have helped to create Gallo's linguistic identity. In this way, Gallo has mirrored Breton's development. Nevertheless, common words (mézë - 'however', du broût - 'ivy', gueroue - 'to freeze', la grôe - 'frost') and some verb forms (such as the metathesis of certain verb conjugations -je subele from the verb subller 'to whistle') are used throughout Upper Brittany.

Oral tradition and written archives

From the middle of the Middle Ages, texts such as Étienne de Fougères’ Livre des Manières (12th century) and the Chanson d’Aiquin (13th century) show phonetic traits that are similar to those of contemporary Gallo and which contrast with the rest of the Oïl-speaking world. While Chrétien de Troyes wrote ‘avoir’ and ‘nuit’, his contemporary Étienne de Fougères wrote ‘aveir’ and ‘neit’. But until the 19th century, Gallo was only transmitted orally, within a largely illiterate rural population. Many names of hamlets come from Gallo (le Carrouge 'the crossroads', le Douet 'the wash house', la Janais, 'a place where jan, meaning gorse, grows'…). These are a reminder that Gallo was still in general use in rural areas in modern times.

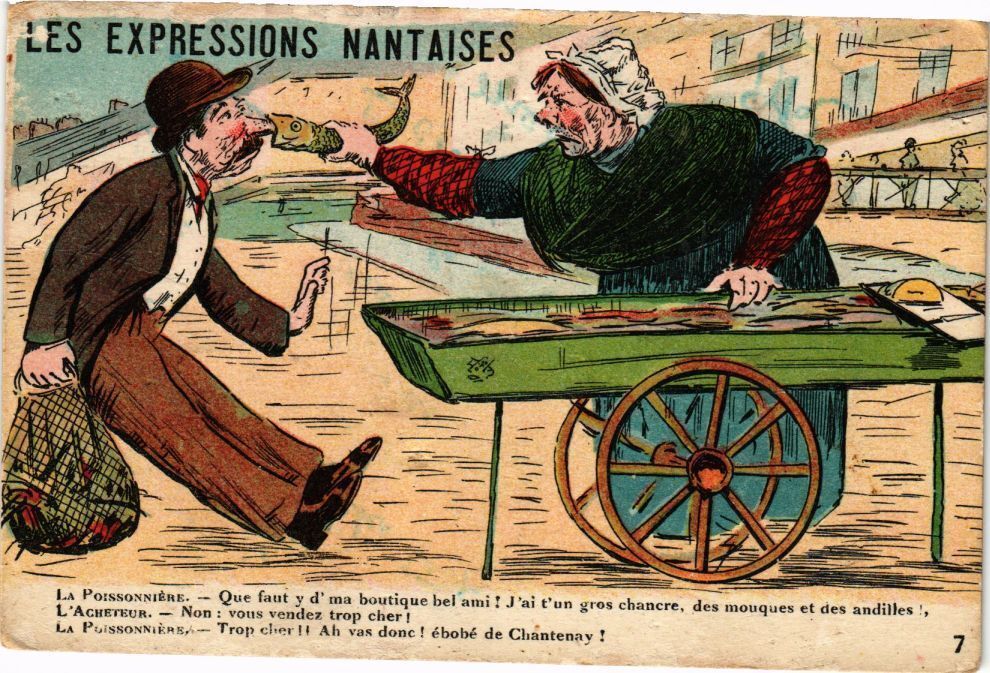

It was in cities that the first glossaries were compiled and published in the 1820s and 1830s, in Nantes and Vitré, in the form of ‘cacologies’ which listed ‘incorrect’ expressions used by the population that ought to be ‘corrected’.

The cities of Upper Brittany attracted the surrounding rural populations, mixing them together. This document shows that Gallo was spoken in Nantes during the interwar period, at least amongst the working classes, to such an extent that it was a part of the city’s identity.

It was under these curious auspices that the trend for ‘language collection’ began. Folklorists at the end of the 19th century had noticed a decline in the use of the language. People from the local educated sections of society liked the idea of saving this linguistic heritage from oblivion, and they published the fruits of their harvest of ‘patois words’ in erudite reviews and magazines. The movement’s crowning achievement was Georges Dottin’s great survey of teachers in Upper Brittany, the results of which were presented as part of the introduction to his Glossaire du parler de Pléchâtel (1901), a text that marked a determining step in the linguistic study of Gallo. Furthermore, the teachers who answered Dottin’s survey regarding the language spoken by their pupils were also agents of linguistic repression within schools. When the first Ferry laws were put in place, schools rejected all languages except French, reinforcing the stigmatisation and decline of ‘patois’. However, it cannot be ignored that this was part of a more widespread process to gradually discredit rural popular culture as a whole, leading to the triumph of modernity over tradition in rural areas.

During the same period, Gallo began to appear in written form in local newspapers. Michel Chalopin has identified 20 or so which regularly published articles in Gallo between 1870 and the Second World War. The tone of these texts was often humorous, but in some cases they also had a political undertone. During the election campaign of 1898, the monarchist candidate from Ploërmel, the Duke of Rohan, was insulted in Gallo in one of the Réveil ploërmelais publication’s columns, as well as on posters. But these written examples were only the tip of the iceberg as far as Gallo was concerned, its wealth of orality having far greater significance (sayings, ditties, tunes, nuances in farming and practical vocabulary…).

It’s not ‘patois’, it’s a language

There was a boom in Gallo artistic and literary expression in the 20th century. Its style was both bucolic (Amand Dagn̈et’s play, La Fille de la Brunelas, from 1901) and avant-garde (Les sept frères, The Seven Brothers, a story collected, written and illustrated by Jeanne Malivel in 1923). In the 1930s a desire to preserve the language emerged within the folklorist community, and in January 1939 the Compagnons de Merlin was created, a regionalist circle whose mission was to deliver Upper Brittany’s "cultural awakening".

The double effect of a decentralised Vichy administration and the Occupying Force’s benevolence towards the Breton movement during the Second World War led to an unprecedented rise in gallèse cultural life. There were Gallo performances at the Théâtre de Rennes (now the Opéra) as well as in rural areas. On Radio Rennes Bretagne, a radio station under German control, people spoke both Gallo and Breton. Based on the example undertaken for the latter in 1941, a first attempt at creating uniform spelling rules was offered by Joel de Villers, an aristocrat from the Loire-Inférieure and a member of the Parti national Breton. Like its Breton counterpart, Emsav, the Gallo movement collapsed during the Liberation of France, due the compromising behaviour of many of its members.

This play, in ‘patois’, was interspersed with songs from the pays de Rennes, collected by Simone Morand. Written in 1938, it was performed many times in Ille-et-Vilaine during the war. The group performed in aid of Secours national, an official organisation which helped prisoners in Germany, but which also became a propaganda tool for the Vichy regime. According to Simone Morand, the group nevertheless declined to put on a special performance for occupying troops.

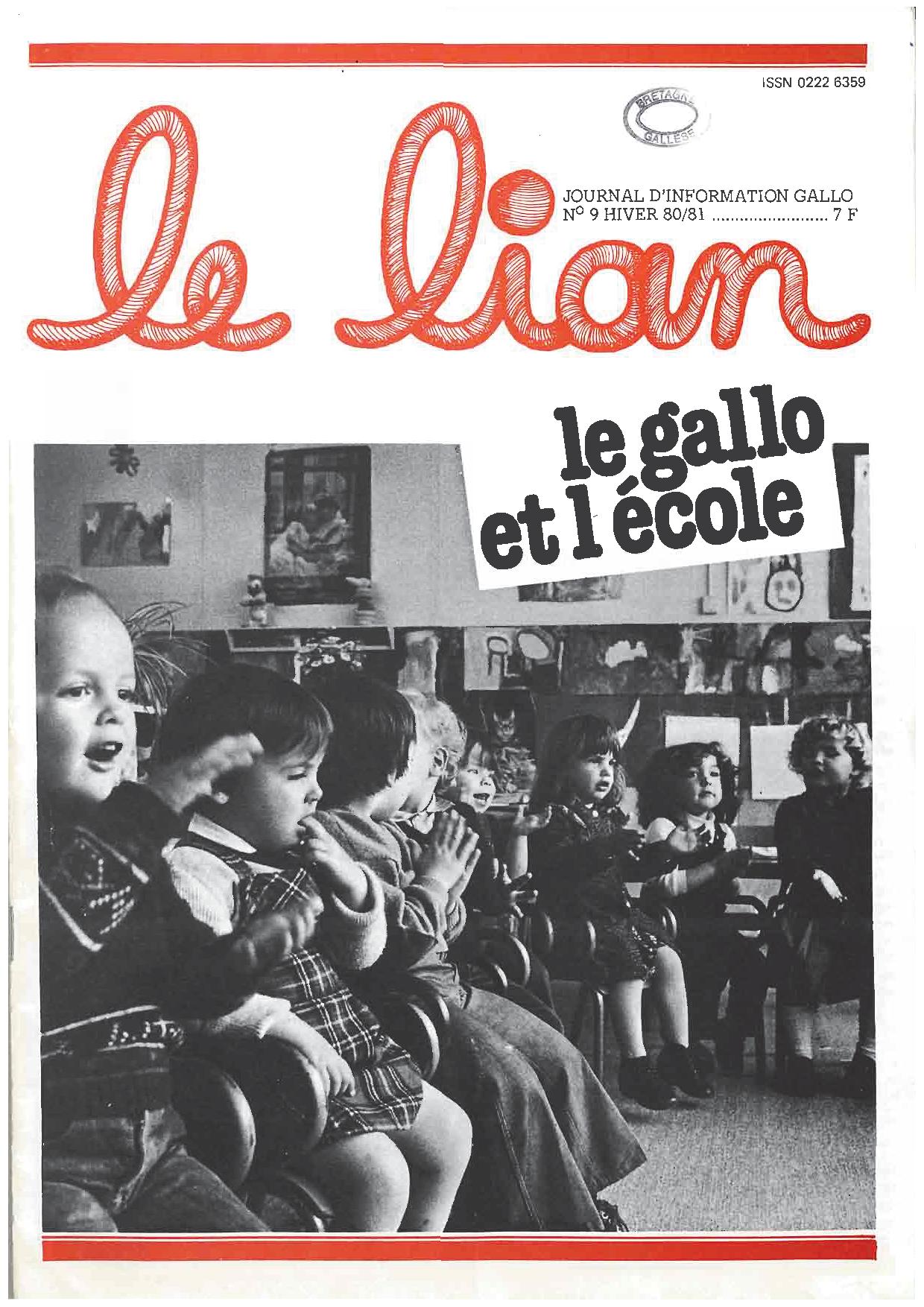

A second Gallo movement emerged after the civil unrest of 1968 which led to a new ideological and cultural context. The association des Amis du parler gallo (now known as Bertègn Galèzz) was established in 1976, and within a few years it became a very active federation under the leadership of young history teacher, Gilles Morin. The emergence of festivals celebrating popular culture (the Bogue d’Or de Redon in 1975, the Fête gallèse de Monterfil in 1976, the Assemblées gallèses in 1979) lent momentum to this dynamic linguistic movement, which succeeded in convincing education department to validate Gallo as a subject option at Baccaleureate level in 1984. In articles from the Lian review, as well as in the many plays written during those years, the language served as a vehicle via which people expressed the social issues of the day.

In 1984, Gallo became the first Oïl language to be accepted at baccalaureate level. With little support, it is not much taught at secondary level today, although initiation classes in primary schools have experienced greater popularity in recent years.

This revival was based on increased knowledge of the language thanks to reference works such as the first two volumes of the ALBRAM (Atlas linguistique de la Bretagne romane, de l’Anjou et du Maine – The Anjou and Maine Linguistic Atlas of Roman Brittany) by Abbot Gabriel Guillane and Jean-Paul Chauveau, published by the CNRS in 1975 and 1982. After the golden age of 1970 to 1980, the 1990s and 2000s gave rise to two different groups of campaigners with two different ways of writing Gallo, despite the fact that published writing resources had begun to multiply, especially dictionaries, grammar references, folklore collections, as well as radio productions with Plum’ FM and musical compositions.

Reorganisation for modern times

In 2004, Gallo was recognised by the regional council as a language of Brittany, like Breton. This was the start of a more assured linguistic policy, including the creation of the Institut du Gallo in 2017, which represented an important milestone. Using the Du Galo, Dam Yan Dam Vèr charter, the institute’s aim is to get communities, associations and businesses in Gallo-speaking territories more involved in the promotion of the language, for example by encouraging the erection of signposts for local place names. Today, this organisation is at the heart of a dense network of collectives (le CAC Sud-22, l’Académie du Gallo, Chubri, Qerouézée, la Granjagoul…) and its actions are largely concerned with teaching Gallo, together with the Cllâssiers association with which it merged in October 2023. The orthographic battle has gradually died down since the 2007 update of the ABCD written form (named after its creators Auffray-Bienvenu-Le Coq-Deriano), which has become the go-to reference even if orthographical flexibility is often the done thing, especially when attempting to describe local pronunciations as closely as possible.

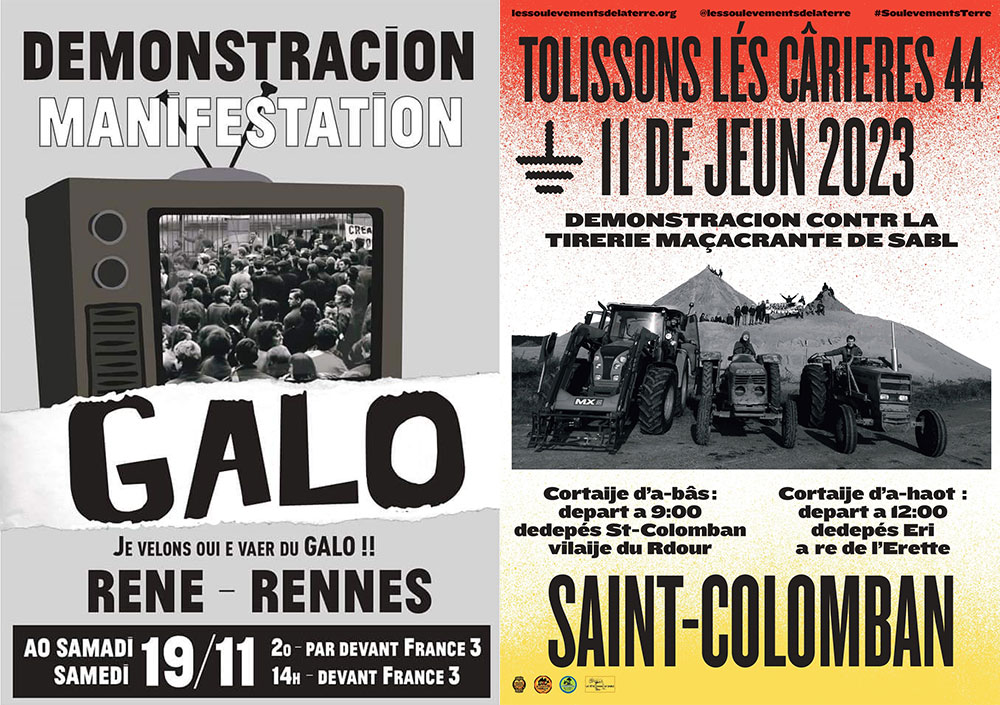

Left: Announcement of a demonstration calling for more Gallo in the media (November 2022). Right: Inviting people to participate in a protest organised by Soulèvements de la Terre against the industrial extraction of sand in the Loire-Atlantique (June 2023). Posters are a way of giving the language visibility, since it does not have a huge presence in public spaces.

A survey in 2018 estimated the number of Gallo speakers at 196,000. These are mainly older people from rural communities. Since 2009, Gallo has therefore been classified by UNESCO as ‘seriously endangered’. Today, new generations of speakers are emerging, free of the stigma so long associated with the term ‘patois’. It remains an endangered language. Bringing it back into use can help to perpetuate ways of describing and naming the world which are very intimately connected with the land, its history and its environment.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill