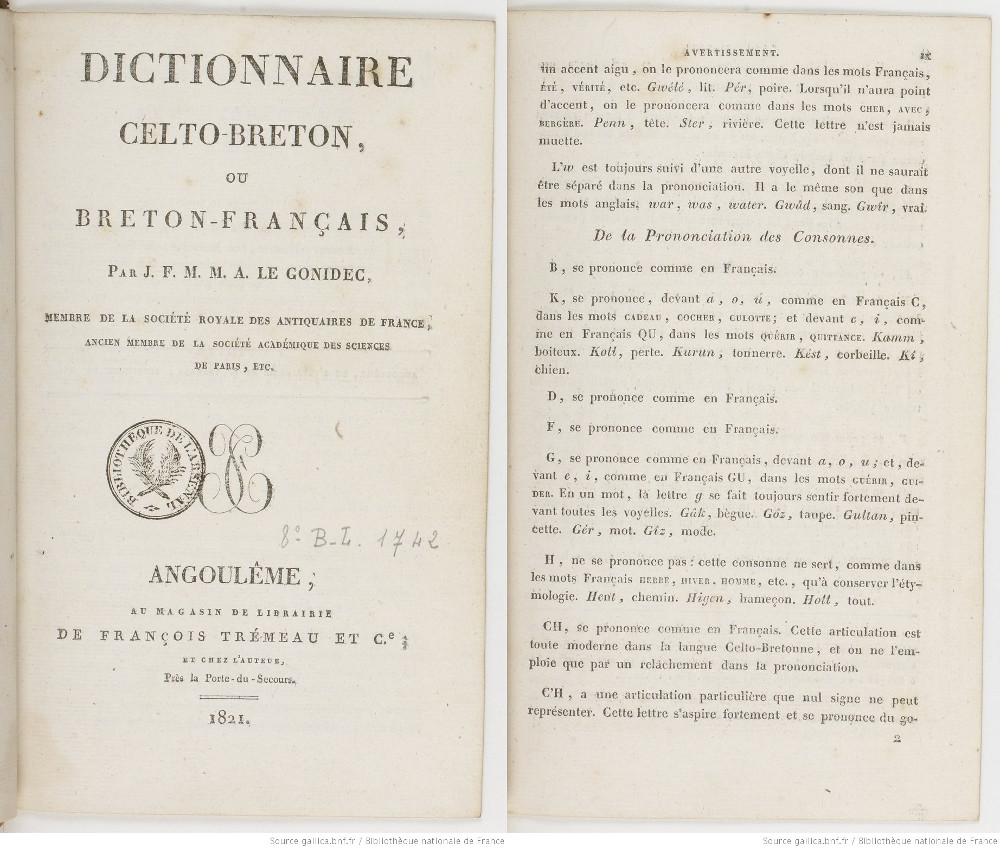

The spread of written Breton for non-literary productions around the XVII century led to the use of spelling models based on Latin and French as they were considered more prestigious. Breton has never been a state language, and thus spelling reforms which emanate from individuals or influential networks are then adopted to various degrees or abandoned but may also coexist. The successive spelling reforms tended to consider the oral use of the language or distance themselves from the French orthographic influence, the linguistic uniformity that reflected a unified Breton nation and possibly an independent state. Each spelling reform kept specific characteristics from the previous ones and established new ones. The oldest stratum is only visible today through the use of–ff at the end of words, such as in some surnames (e.g. Le Goff) or place names (e.g. Dourduff). Maunoir (1659) introduced the spelling of consonantal mutations and the use of c’h. Le Gonidec’s reform (1807) added k and w, whereas the KLT reform (1908) instituted the tilde (ñ) for nasalization, the y- and lh, etc.

For the last half a century, three spellings coexist peurunvan (1941), skolveurieg (1953), etrerannyezhel (1973). Although the etrerannyezhel was the spelling used by the UDB (political party) in the 1970s and for the Assimil language learning method as well as the Favereau dictionary, it is only very marginally used nowadays. Although many texts were edited using the skolveurieg spelling system by the publishing house Emgleo Breizh, its closure in 2015 marked the end of its public use. Thus, today it is the peurunvan spelling system that is mainly used. Those in the teaching community, from primary to secondary, use it and rely on a vast number of schoolbooks written in this spelling and a large number of literary texts have also been published using it. Finally, public authorities, supported by the Breton Language Office, promote it, and use it for bilingual signage and other translation work.