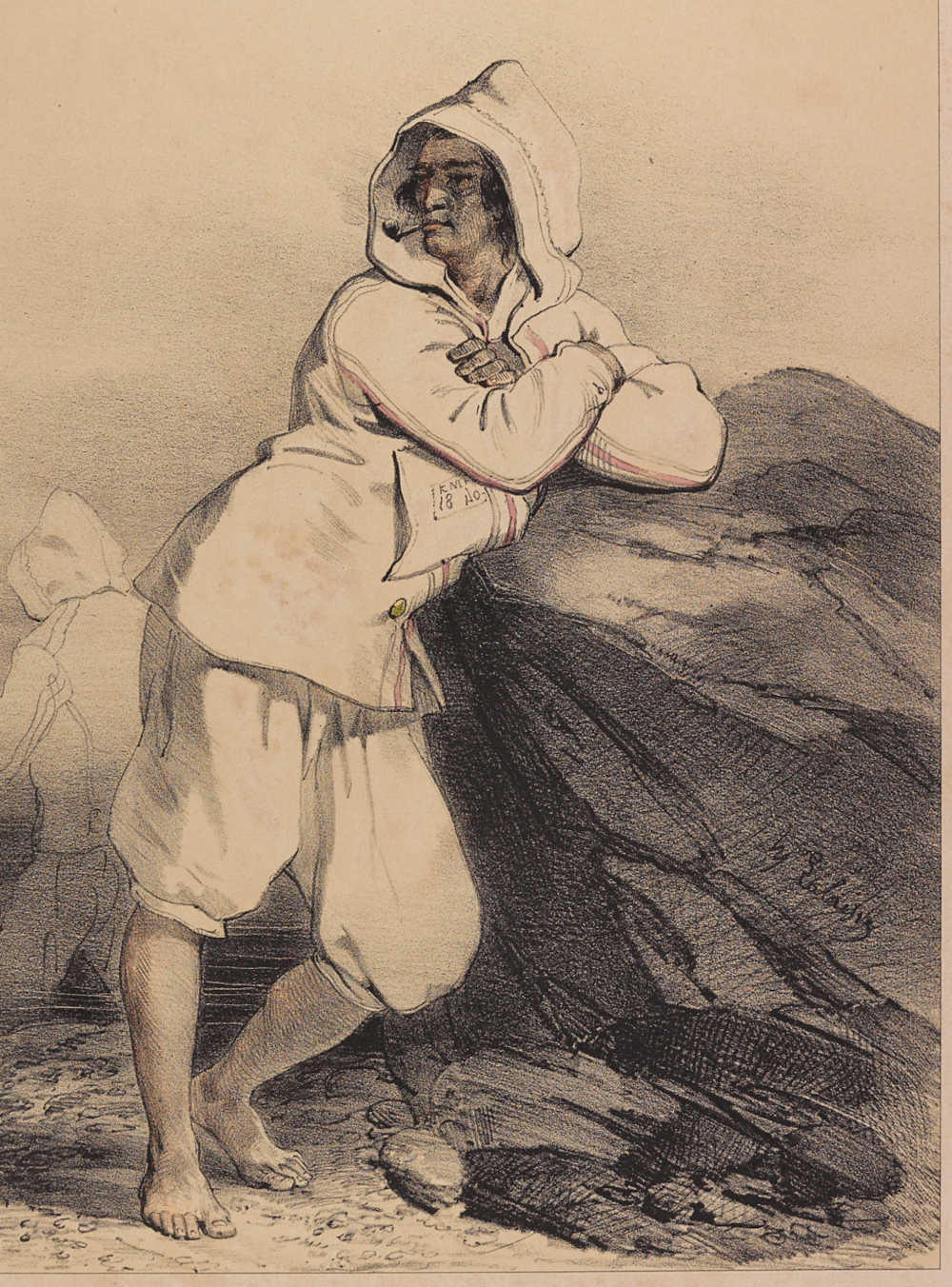

The Kab an aod, or “shore cape” was originally worn in the pays Pagan, in North Finistère by goémoniers (seaweed pickers) who were continuously exposed to the harsh coastal elements and therefore needed clothing that would both keep them warm and withstand the laborious nature of their work as they harvested seaweed around the base of the rocks. The personality of the mariners who wore them was just as memorable as the kabig’s unique cut, the fabric’s properties and striking shade of off-white. The oldest image of a goémonier wearing a kabig was left to us by a travelling artist who was fascinated by regional costume. On one of his journeys to Brittany during the summer of 1844, François-Hippolyte Lalaisse (1812-1884), a professor at the Paris School of Engineering, drew a goémonier in his kabig, an engraving of which was created as part of a collection of prints published a year later.

Its inclusion in the collection ensured the kabig’s survival. The success of the Galerie armoricaine album published in Nantes by Pierre-Henri Charpentier, led to further reproductions: lithographs, press reproductions, a stage costume for the performance of “Le Fanal”, created at the Théâtre de l’Opéra in 1849…

A relaunch thanks to its working-class Breton origins

However, it was in the pays Bigouden, where the traditional kabig had never even existed, that people took the first steps towards relaunching it as a fashion item. Indeed, Marc Le Berre (1899-1968), a member of the Seiz Breur and a nationalist activist, hoped to design a modern Breton look and he took inspiration from the kab an aod as early as 1937. Many people from Brest, Landerneau, Quimper and Rennes holidaying in Brignogan could be seen sporting the kab gwenn.

These holidaymakers were given the nickname “lakzien” (pronounced lakishenn), meaning “those who do nothing”, by locals. After the Second World War, Marc Le Berre focused on reproducing the original silhouette of the goémonier work coat. He made a copy of an example from the Musée departemental breton’s collection. Thanks to this archive piece, he was able to reproduce the cut, buttons, pinked edge seam, topstitching, selvedge, hood and cuffs of the traditional model. He set about reproducing it first at the Kernisy sewing atelier, and from 1951 in Quimper. It was later manufactured at the family atelier Les Tissages de Locmaria, under the brand name L’enfant d’Armor and also at Ruallem in Quimper.

Entrepeneurial spirit: the key to longevity

For Pont-l’Abbé’s Le Minor clothing brand, known for its resolutely commercial approach, the kabig was a timely target for its famous embroideries, and in 1950 it jumped on the kabig bandwagon. They made them for men, women and children, generally keeping them long. They replaced the traditional front central pocket with deep side pockets and often added a collar. Finally, they often produced them from coloured fabrics which they would decorate with embroidery. In 1974, 6,000 Le Minor kabigs made by more than 300 workers were released from Le Minor’s workshops in the pays Bigouden. At the same time, a bold advertising campaign was featured in national magazines.

A vibrant sense of determination within the Breton cultural movement

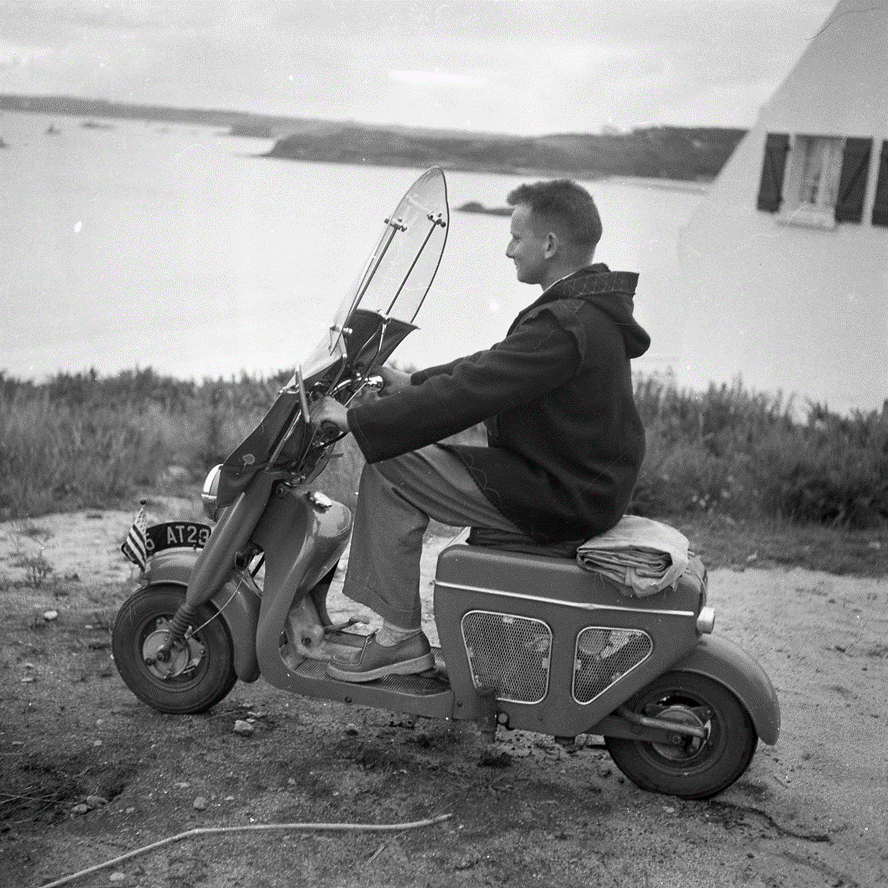

This commercial undertaking achieved an exceptional level of success in the fashion industry primarily because there was such strong demand. Starting in the 1950s, bands and musicians from both Lower and Upper Brittany started wearing kabigs. For example, the bagadoù (traditional pipe bands) of Plouguerneau, Brest, Quimper, Cléguer, Ploërmel, Fougères, Morlaix, Nantes, Rennes, Redon, Paris, and Marseille… Within four of five years, the coat became universally recognised as Breton. It was a practical alternative to the more local and costly outfits which were often unsuited to carrying musical instruments during parades. It was also the moment at which the original name, kab an aod, was replaced with the term kabig. Until then, the latter had only been used in the context of children’s clothing.

Around the same time, the kabig also made its appearance on the silver screen. On the advice of Herry Caouissin, actors in the films Dieu a besoin des hommes, (God Needs Men, 1950), inspired by Henri Queffélec’s novel Un recteur de l’île de Sein, published in 1944, and Le Mystère du Folgoët, wore a blue kabig, despite the fact that no seaman from either location had ever really worn one.

From then on, the kabig became the ultimate example of maritime clothing. The passion that young stylists like Val Piriou, Bleuenn Seveno or Owen Poho showed and continue to show for the kabig prove that it still has an undeniably seductive quality. In the 1960s, Breton ethnographer, artist and designer René-Yves Creston described it as “the national costume of Brittany’s youth”. Ten years later, that passion was passed on to other regional activists who managed to flip the negative connotations sometimes associated with the goémonier work coat on their head. Today, Goulc’han Kervella, theatre director with the Ar vro Bagan theatre troupe in Plouguerneau, wears a kabig because he feels it embodies the Breton sentiment and ambition to “live and work in Brittany.”

Although for many years people still associated the kabig’s origins with the goémoniers, it has taken more than one collective memory to ensure its longevity. In fact, its success is the result of a three-stage transformation. First, the kab an aod broke away from its traditional function as workwear. Next it became popular among a group that was socially distinct from the locals of the pays Pagan who only wore it within a work context. Finally, it became established in different geographical areas, and especially in cities. It remains a striking example of progress from a local to regional, if not national level.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill