Breton salt, a fundamental export for the food industry

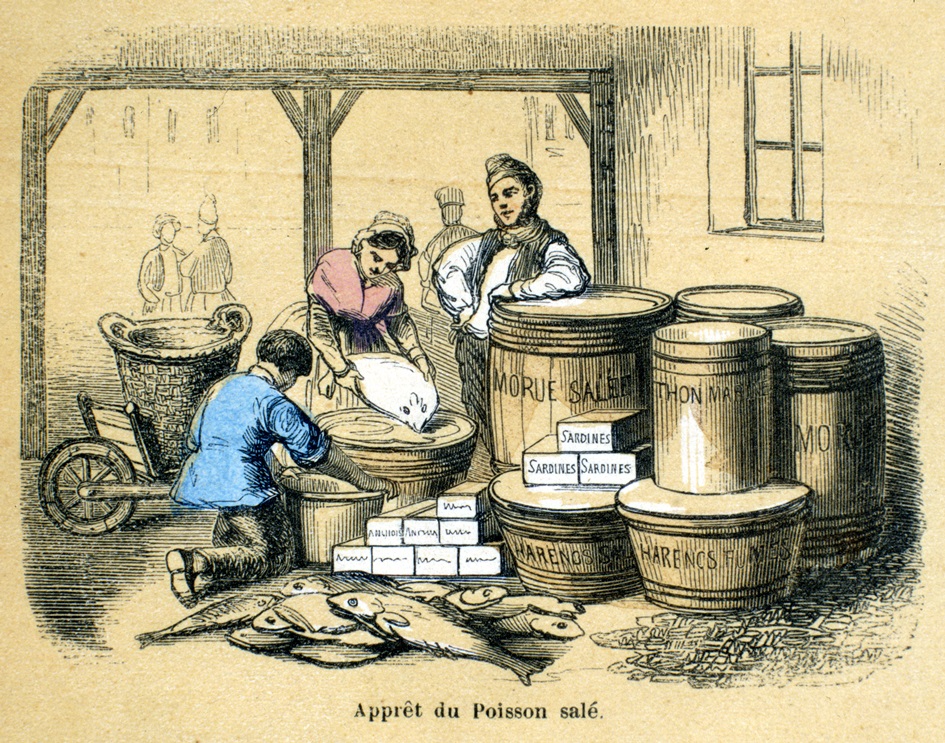

Salt and its commercialisation greatly contributed to Brittany’s prosperity. Its antibacterial and hygroscopic (moisture absorption) properties meant it was fundamental for preserving meat and fish.

Throughout the Middle Ages and into the Modern Era, the population’s needs increased, driven by the rise in herring fishing in north-western Europe and, from the 16th century, cod fishing, as well as the preparation of salted meats needed for long-distance sea voyages.

Transporting it from salt marshes meant relying on all the usual transport networks: roads and pathways, rivers and of course the sea.

The transport of salt by river from at least the early Middle Ages is indicated by the tonlieux exemptions enjoyed by churches and abbeys on deliveries from the salt marshes along the bay and heading up the Loire and its tributaries. Such river traffic close to Nantes, which was an entry port into the French kingdom, remained considerable until the 16th century, with as much coming in from the salt marshes south of the Loire as from those to the north.

Early recognition of a regional product

From the 13th century, Breton salt also became part of international trade, firstly with the British Iles, and later, from the end of the 14th century, with Germany, Flanders, Brabant (Belgium) and Zeeland (Netherlands).

This was the result of a trade association between cities along the North Sea and Baltic coasts, when they joined forces as part of the Hanseatic League. Their ships came to load up on the specifically named Baiesalz salt at Collet Port in the Bay of Bourgneuf.

The salt marshes on the northern side of the Loire were not a part of this foreign trade setup. However, Guérande salt was exported to the British Isles. It was transported by local sailors who were also transporting wine from Bordeaux to ports in Cornwall and Devon, and sometimes Flanders and Holland too. Its notoriety in the British Iles is illustrated in Le vroy Gragantua, an anonymous story from 1482, which tells of King Arthur and Merlin, wishing to salt their deer, asking Gargantua to fetch them salt from “Guerrande”.

Specialist ports and prioritised destinations

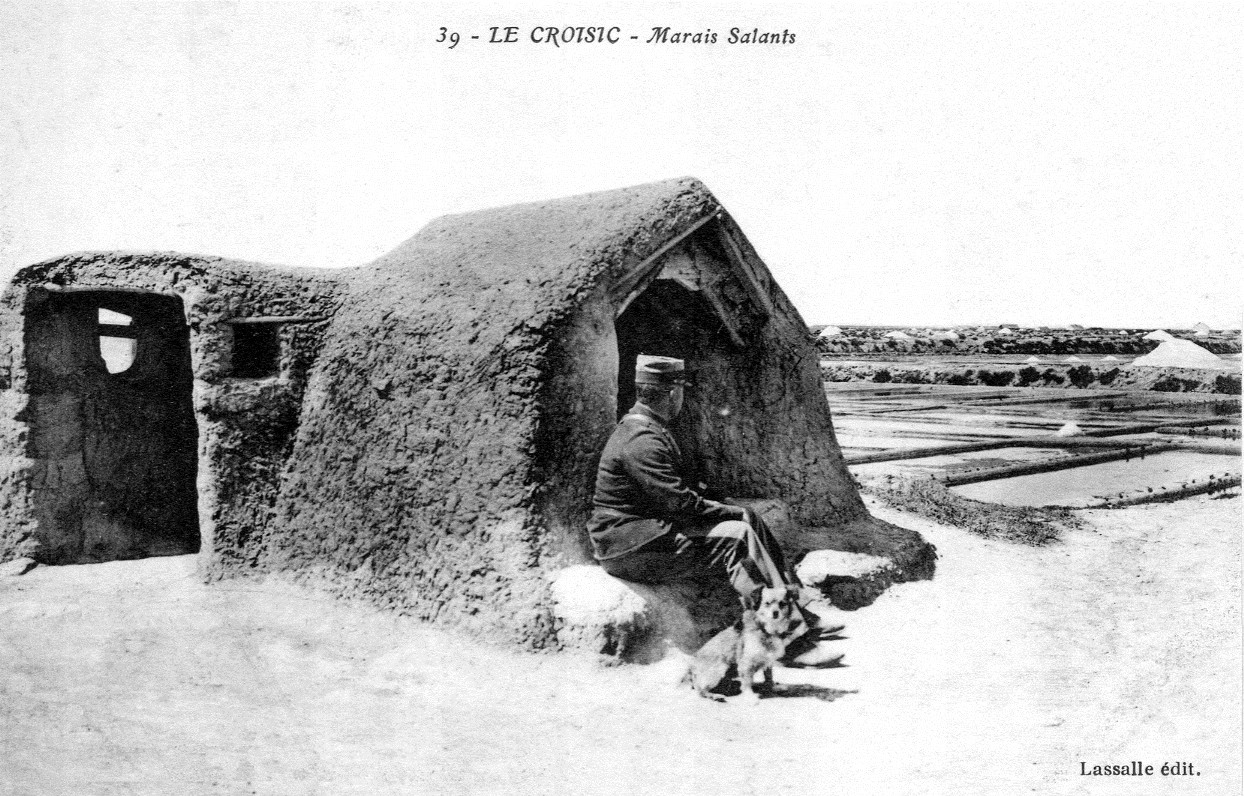

Fairly early on, Le Croisic and Le Pouliguen ports, which controlled entry to the salt marshes, seemed to each manage their own commercial traffic, le Croisic’s heading towards northern Europe and Le Pouliguen’s towards the Loire and the Spanish peninsula.

The ports of Piriac and Mesquer were also involved in the transportation of salt along the Breton coast and towards inland Brittany via the river Vilaine, and the outer harbours for Rennes, La Roche-Bernard and Redon (particularly Saint-Sauveur Abbey) had large salt stores.

The Guérande salt trade’s horizons

Trade traffic during the medieval period with the north of the Spanish peninsula was consolidated by a commercial alliance between Spain and Nantes. Until the end of the 18th century, when Great Britain’s own salt mines began to be exploited on an industrial scale, ports in the British Iles remained important trading zones for Guérande salt.

In fact, at the end of the 17th century, salt trade from the port of Le Croisic was mainly dominated by English ships from ports in Cornwall, Devon, Wales, Scotland and the Irish coast.

Flemish, Dutch and representatives from other nations in the North were only present occasionally, whereas the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Basques were regular customers. A change in the political context later meant the Dutch could slowly take over the trade lines. In the middle of the 18th century, thanks to its dynamism in the marketplace, Le Croisic became the Kingdom of France’s second biggest Atlantic trade port with the countries in the Baltic Sea. Over the following decades, the Scandinavians took over from the Dutch.

19th century: scaling back the maritime transport system

After the Revolution, the maritime export outlets for Guérande salt remained numerous in ports in the North Sea. Belgium and Zeeland’s refineries treated the salt and re-exported it towards the northern European markets. At the same time, there was also export flow towards Scandinavia. Salt remained in demand at the French and Breton ports based in the Channel. These ports specialised in the salt preservation of produce brought in by fishing boats.

But the distribution of industrially-produced salt in the Atlantic salt markets, which may have been encouraged by the Continental Blockade, considerably reduced the traditional markets and port activity in the Guérande region, which were suddenly in competition with those of the ports of Nantes and Saint-Nazaire.

Transporting salt by land was therefore reintroduced along departmental roads in the West and later via the railway network. From 1880, land transport methods were became ever easier and Breton salt was able to retain a significant place within regional markets, helping to compensate for the loss of international markets.

Overland transport and the exchange of goods

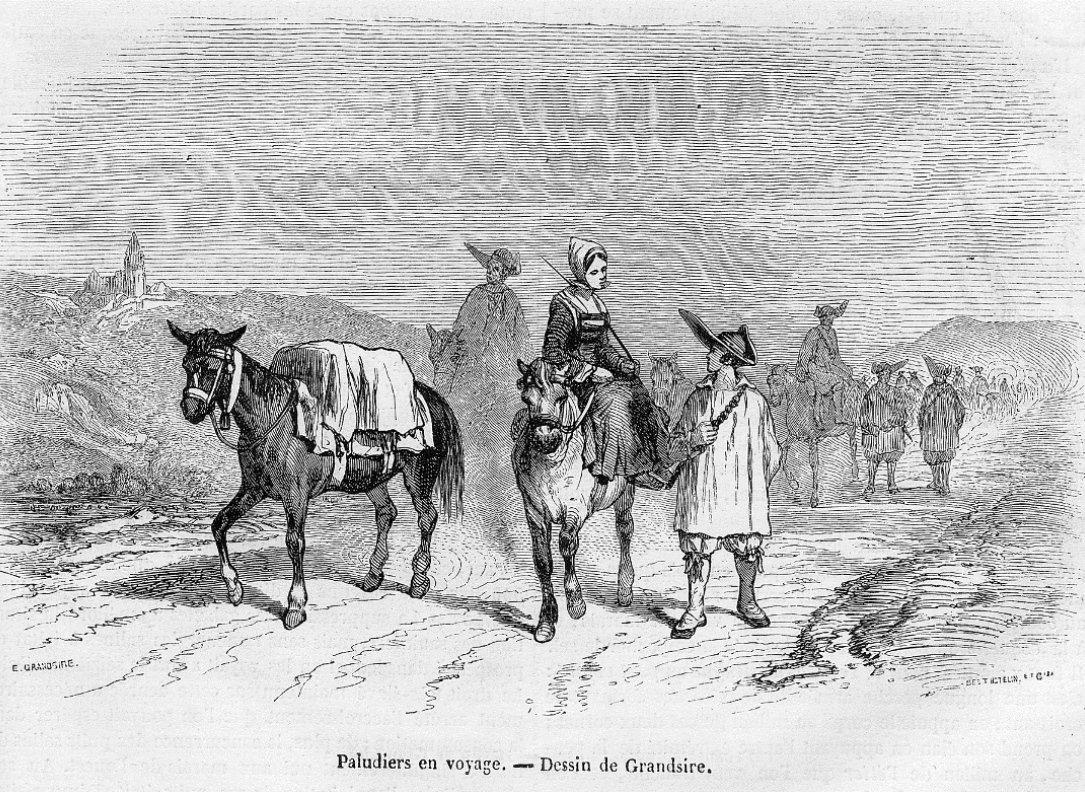

![Salt workers or ‘paludiers’ from Batz on a journey, Galerie Armoricaine. Traditional clothing and picturesque views of Brittany, [1845] plate 5, François-H. Lalaisse - Musée des marais salants collection, inventory number 91.7.3 Paludiers du bourg de Batz en voyage, Galerie Armoricaine. Costumes et vues pittoresques de la Bretagne, [1845], planche 5, François-H. Lalaisse - coll. Musée des marais salants, n° inventaire 91.7.3](/becedia/sites/default/files/medias/dossiers-thematiques/le-sel-et-son-commerce/Lalaisse%20Coll.%20Mus%C3%A9e%20des%20marais%20salants%2C%2091.7.3%20saunier.jpg)

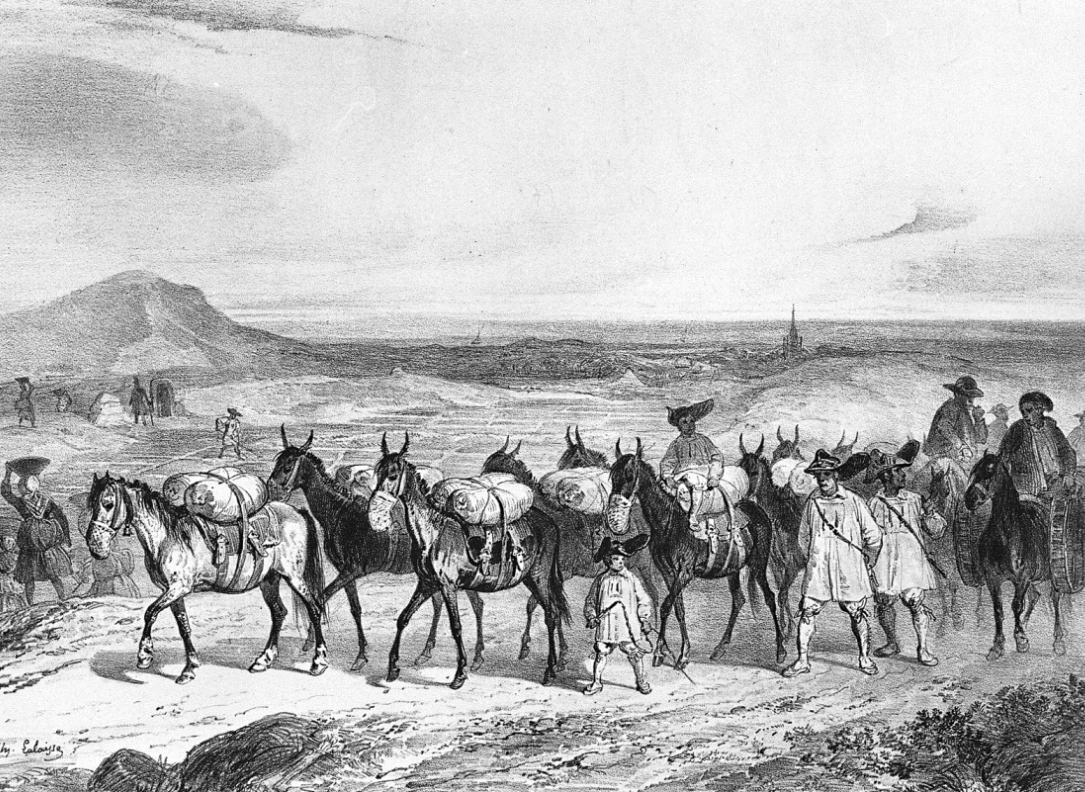

Compared with maritime and river transport, transporting salt via land was very laborious for a long time and only worked for small volumes. Transporting salt by cart over short distances directly from the salt marshes dates back to the Middle Ages, but most traces of the activity are form the Modern Era. The documents mainly relate to transport organisation and the quantities involved. In contrast to maritime trade, which mainly concerned merchants brokering large volumes, land trade was carried out by people from the marshes themselves, the saltworkers or paludiers, and specialist land transport workers called sauniers.

These paludiers and sauniers practised a regional goods exchange system where no money changed hands, established as a form of tax exemption by Duke Jean V. The people from the marshes sent boats loaded with salt from Le Croisic and Le Pouliguen or Mesquer towards ports in Cournouaille and the Vannetais. The charterers would bring caravans of beasts of burden to meet the boats, then head inland into the Breton countryside via the sauniers and mule driver routes, going from farm to farm and exchanging the salt for wheat, rye or barley. The cereals would then be taken to the Guérande region via the sea or on the backs of mules.

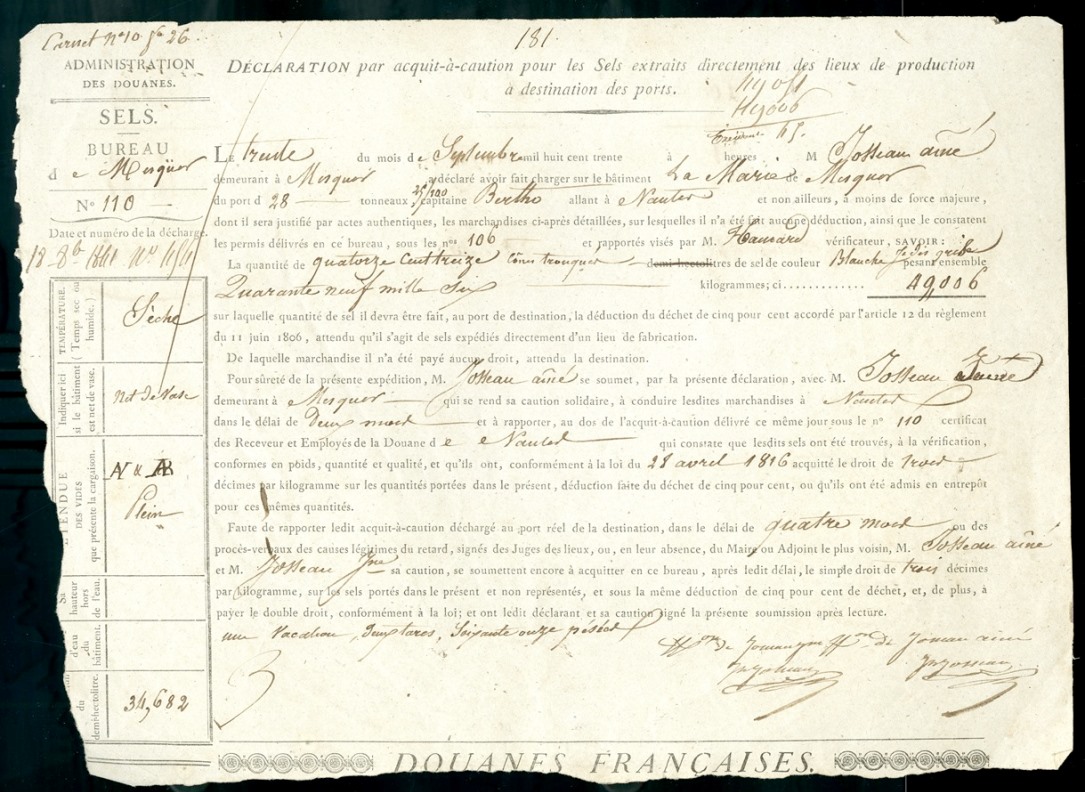

In 1790, the National Constituant Assembly banned this form of exchange of goods. Louis XVIII reintroduced it later in 1816 for a half century, but in a way that was much less beneficial to the paludiers and sauniers. Meanwhile, in 1806 a tax on the transportation of salt was established, which made life more difficult for many. Salt would now be taxed as it left the marshes and this would have a negative effect on the industry until 1945. During this long period, customs officers nicknamed gabelous (from gabelle the name of the Ancien Régime’s salt tax, which until that point had not applied to Brittany) became an unavoidable part of life in the salt marshes.

Illustrations

Translation: TillyO'Neill

![Extract from plate 106. “Fishing boat at sea, cod fishing”, engraved by Bernard, Traité des pêches by Duhamel du Monceau, published between 1769 and 1782. Figure 2 shows “a stand, with the ‘décolleur’ (d) standing in a barrel wearing a long leather apron […] at the other end of the table stands the ‘habilleur’ (e), also inside a barrel wearing a smaller apron; near him is a wooden pipe (f) into which he throws the cod he has cleaned, which fall down into the hold […] (c) is a ‘ligneur' or ‘lignotier’ standing in barrel b, with the handrail on which he rests his fishing line […]”; Figure 3: “A is a salter, putting the cod in the ‘first’ salt, B are the ship’s apprentices who bring the salt to the salter on palettes”. Private collection Extrait de la planche 106, « Pêches de mer, pêche de la morue » gravée par Bernard, Traité des pêches de Duhamel du Monceau, édité en 1769-1782. La figure 2 présente « un étal , & à un bout le Décolleur D qui est dans un barril avec son grand tablier de cuir […] ; à l’autre bout de la table est l’Habilleur e, qui est aussi dans un barril avec un petit tablier ; auprès de lui est un tuyau de bois F, dans lequel il jette les morues qu’il a habillées, & elles tombent dans la cale […] ; C, est un ligneur ou lignotier dans son barril B, est la lisse sur laquelle il appuie sa ligne […] »; la figure 3 « A – est un saleur qui met ses morues en premier sel B – sont les mousses qui prennent du sel sur des palettes pour le porter au saleur » - Coll. particulière](/becedia/sites/default/files/medias/dossiers-thematiques/le-sel-et-son-commerce/Extrait%20de%20la%20planche%20106.jpg)