The Birth of the Revolution

For the revolutionaries, Rennes was the “birthplace of liberty,” a way of saying that it was at the confluence of Ille-et Vilaine that the Revolution began. It is however true that this prestigious title is challenged by Grenoble. In fact, if we consider the Revolution as the union founded on the idea of a motherland, then Grenoble is indeed where it all started. But if we see the Revolution as a “passage towards physical violence and conflict in the streets caused by the inability to get along due to the confrontation of ideas and words” (Michel Denis), violence which can lead to the rejection of nobility in a radical way, then it was at Rennes that the process was set into motion. In short, the events in Grenoble announced the Revolution of 1789-90 whilst those in Rennes prefigured the 1793-94 Revolution.

From Political Altercation…

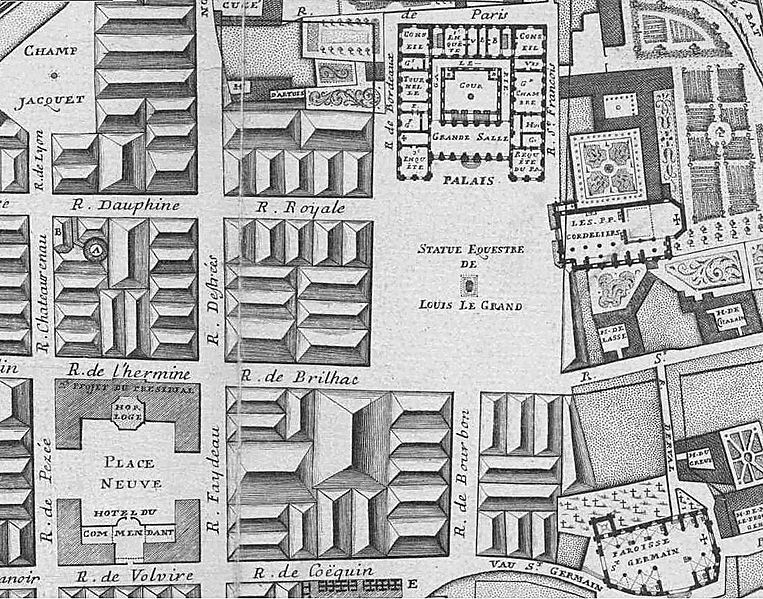

From spring 1788 onwards, Rennes, like Grenoble, was ablaze and passionately defending its parliament that was under threat from royal power. The monarchy wished to deny the parliaments’ political powers in court, which was believed to be the reason that no tax reforms were possible. The crowds rioted in favour of the magistrates and the army was on the brink of causing a massacre. Soon, the royal power retreated, but other incidences were triggered by the opening of the assembly of the Estates of Brittany.

The assembly, which met every two years in the Cordeliers convent which was adjoined to Rennes’s parliament, became the stage for a conflict that mirrored the national political debates. In fact, Louis XVI decided to summon the Estates-General, which was a victory for those who opposed the government’s policies. But they soon divided themselves into those who believed the Estates-General should assemble according to their traditional form and those who believed that more space should be granted to the Third Estate. The same dispute took place in Rennes, where the bourgeoisie demanded a reform that would concede more power to it and that would also limit the influence of the nobility in the provincial assembly.

….to Conflict in the Streets.

Tension was rising partly due to the circulation of pamphlets which, in particular those written by Volney, could take a radical stance and in turn contribute to the hardening of positions. At the beginning of January, Louis XVI suspended the Estates of Brittany in the hope of regaining peace. The Breton nobility, who came in mass, refused to disband and stayed in the convent. In an attempt to resolve the situation, the nobility seemingly instigated the strong sense of discontentment that disturbed the town which was threatened by the scarcity of grain.

Therefore, on January 26th porters of all kinds- recognisable by the leather belts they wore and who were called “bricoles”- regrouped in front of the parliament to express their discontentment. There, they were received by members of the court who were historical allies of the nobility Estate and they obtained a promise that the municipality would be asked to take action to reduce the price of bread. They were also told that the situation was due to the egotistical attitude of the bourgeoisie. The protest was thus to show that the latter did not have the support of the lower classes since it did not represent them and that the Third Estate was consequently divided.

The bricoles then challenged a group of young people who were observing the scene from a café on the Palace square. They were students from the law faculty and were strongly in favour of the reforms. Violence ensued but the incident did not last for long. Amongst the students, there was the future General of the revolutionary armies, Victor Moreau, who figured as the organiser of the retaliation that would shortly appear.

The First Deaths of the Revolution

It all could have ended there, but the following day, on January 27th, it was the turn of young people who had been harassed the day before to gather in front of the Parliament to protest against the blows they had suffered and against those who they judged to be truly responsible for the violence of the working class, in other words, the nobility. A few metres away, in the Cordeliers convent, sensing that the protest was in fact a provocation, the gentlemen decided to go on an outing. The charge with sabres clearly directed at the young bourgeois who were also armed, trigged violent confrontations. Amongst the combatants figured the young Chateaubriand who would much later on leave a famous account of this day.

The death toll was quite heavy. At least two died and many were injured. In the “patriot” camp, emotions ran high provoking a wave of solidarity which was illustrated by the hundreds of young people who came from all over Brittany to lend a hand to their “brothers.” As this movement of fraternisation, that would culminate a year and a half later with the Fête de la Fédération in Paris, made a start, the nobility made a choice to withdraw to their territories. Considering that the Estate-General did not meet according to custom, it refused additionally to send deputies there. Conversely, in the opposing camp, the intense politicisation of spirits triggered a dynamic which would make deputies who were generally Breton and from Rennes in particular, the leaders of the national debates that would create the foundations for the future “club des Jacobins.”