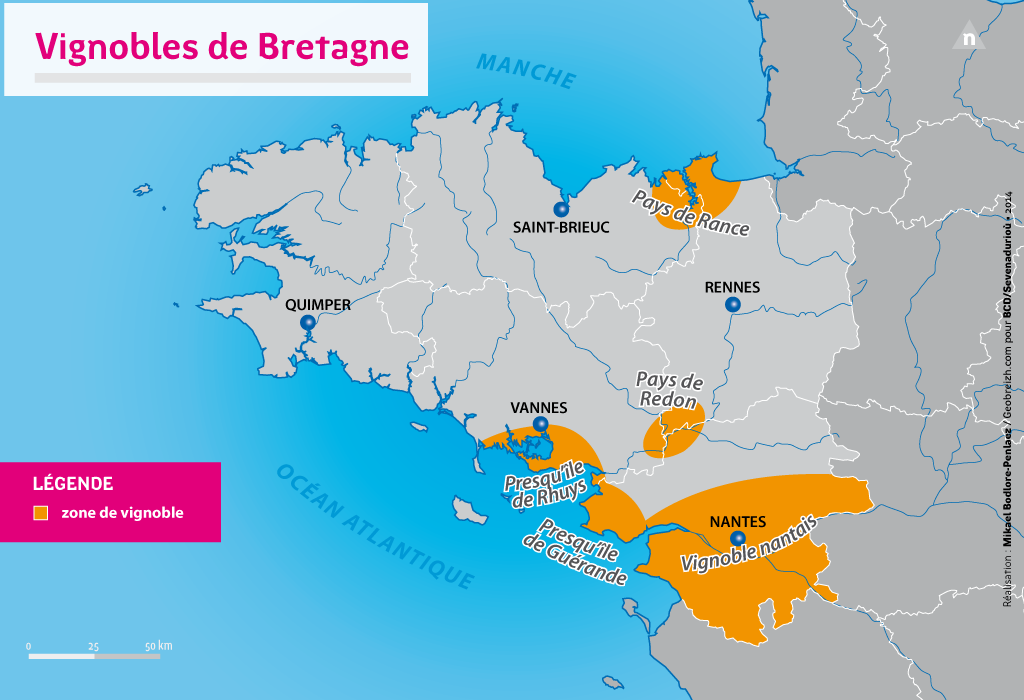

Around the river Rance

In the pays de Rance, the northernmost location for Brittany’s vineyards, there is no mention of winegrowing past the 18th century. Undoubtedly active from the Early Middle Ages, its existence is formally recorded from the 11th century around Dinan, on both sides of the Rance all the way to the sea, as well as throughout the Clos Poulet area (St Malo). The reasons for its disappearance have not been clearly established, but it seems probable that imports from Paris, Poitiers and Bordeaux of better quality than locally-made wines became more popular. In addition, a significant dip in temperatures thanks to a climate event around 1740 may have affected production.

Around the Gulf of Morbihan

On the Rhuys peninsula, it’s also impossible to provide a precise timestamp for the first vineyards. Perhaps St Gildas, who founded a monastery there in the 6th century, planted them! Vines were certainly present at the start of the 16th century and were maintained until 1993, the year of the last officially declared harvest in the area. The region's most prosperous winegrowing era was at the end of the 19th century when it converted from winemaking to the production of eaux-de-vie. These enjoyed critical success, especially the Fine de Rhuys. This change was a result of the decimation of the vineyard at Cognac by phylloxera around 1880. The parasite eventually reached the Rhuys area in 1903. The vines were replanted after the First World War, but on not nearly such a large scale, and mostly using hybrid plants. They were later dug up.

The lower valley of la Vilaine

In Redon, vines were part of the landscape until around 1950, although by the beginning of the 19th century they had were vastly reduced, barely covering 300 hectares. Redon had a port which served as an outer harbour for Rennes, which undoubtedly put any local winegrowing at a disadvantage, since better wines from other areas (especially Bordeaux) were easy to import. It is likely that the monks from Saint Sauveur monastery were the first local wine growers, even if the monastery’s cartulary indicates that their winegrowing properties were mainly further afield, on the Guérande peninsula and in the pays de Retz.

The Guérande region

Further south, on the Guérande peninsula, winegrowing has featured since the Middle Ages. The wine produced there was just as profitable as the Bordeaux wines imported via the Guérande marina, especially in England. The vineyard, situated on a slope which overlooks the bay of Traict, extended from Piriac to La Baule. Its south-westerly orientation combined with the slope’s gradient were both favourable to winegrowing in a region close to the northernmost point at which viticulture was possible, and where very particular climate factors were required for an optimal harvest Some plots acquired real local notoriety (Congor, Clos de Rignac). The oldest mention of viticulture in the area is from 831. It concerns a piece of land belonging to Redon’s Saint Sauveur monastery located in Piriac. At the end of the Middle Ages, local wine production is estimated to have been close to 20,000 hectolitres. Pineau d’Aunis, a grape variety from the Anjou region, is said to have been introduced by Benedictine monks from the Saint-Florent-le-Vieil monastery at the Escoublac priory. But this fact, discerned from a document from the 18th century, which itself had been written based on a separate document from the 11th century, is in fact erroneous. There is therefore no reason to suppose that the Guérande grape variety known as Aunis is the same as Pineau d’Aunis. In fact, the information collected regarding the external morphology and physiology of the variety suggests it is actually Chenin. However, records of the different grape varieties on the vineyard suggest a diverse and original selection, in contrast to other Breton vineyards. Was this because they had access to the sea? Perhaps. Like its neighbours in Rhuys and Redon, the Guérande vineyard disappeared towards the end of the 20th century, having been ravaged by phylloxera in 1890 and replanted with hybrid plants, the cultivation and use of which was eventually banned.

Nantes region

The vineyards of the Nantes region differed from the above in terms of size (around 17,000 hectares today), which also explains their survival. Today, as the region emerges from a very difficult economic context, half its wine production carries the AOC label. Since the end of the 19th century until the Revolution, the area produced an eau de vie mainly made from Gros-plant. Until the emergence of phylloxera in 1884, the area also produced basic wines that were drunk locally, as well as along the south coast of Brittany and the north coast of the Vendée. The rise of Muscadet and higher quality wines dates from the 1920s. Its superiority was confirmed when Muscadet wine was given the AOC label in 1936. In 2011, three locally-produced Muscadets were given the AOC label: Clisson, Gorges and Le Pallet. Seven others are set to follow. Certified as the highest quality wines, they should be more attractive to consumers.

Toponymic traces

All the regions mentioned above carry traces of their viticultural past in the names of hamlets or parcels of land, even if the vines are long gone. For example, on the right-hand bank of the Rance, where the river widens, you can find L’anse de Vigneux, The Bay of Vines; in Sarzeau there is a road called Goh viniec meaning Old Vine; Redon has a road called rue de la vigne; in the Napoleonic land registry in Guérande, three parcels of land are grouped together under the name of port au vin and most villages have a rue or impasse de la vigne.

Could Brittany become a winemaking region once more? The chances are high, and in fact it already is thanks to the several dozen “heritage vineyards” established over the last 20 years, as well as several established as commercial endeavours since 2016, the year in which winemaking was made legal in the region. The former, with no financial objective, have encouraged social connection in the places where the vines have been planted. Maintaining them requires a collective effort, including some very enjoyable gatherings, especially during the harvest season. As for the professional vineyards planted more recently, they produced their first vintage in 2022.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill