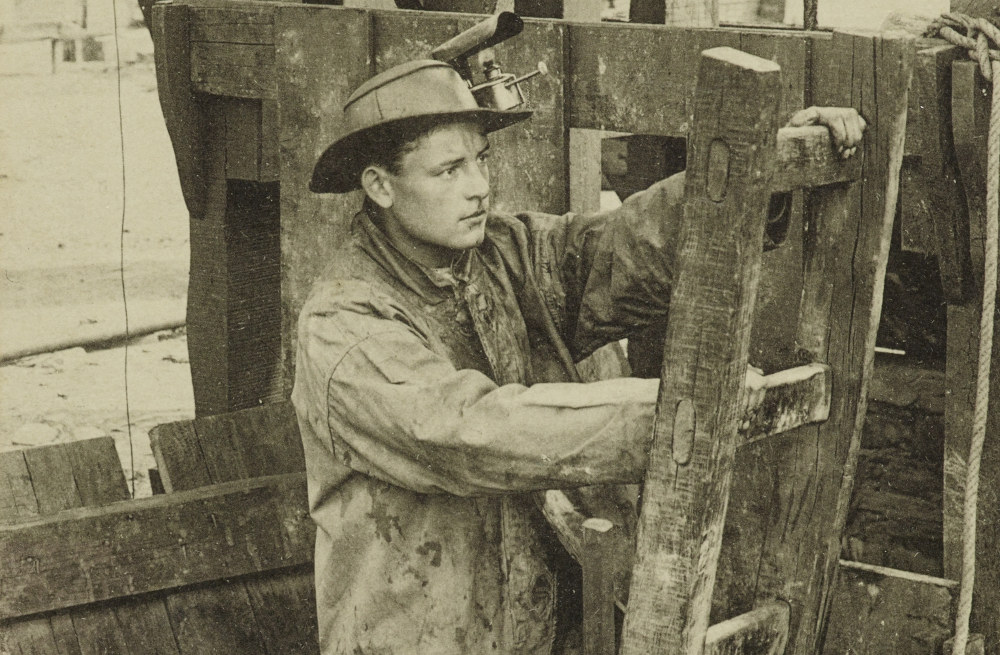

For a long time, workers had to make do with what little they had, protecting themselves by accessorising their everyday clothes: shin guards made with mops held up using inner tube cut offs for quarry workers; reinforced aprons for woodcutters, clogmakers and blacksmiths; cover-alls and hoods, such as the kalaboussen, which were worn by the goémoniers (seaweed pickers) of Léon. At sea, sailors commonly wore big hooded capes, known as kapo bras, made from strips of sail canvas. To keep the rain, sea spray and wind at bay on fishing voyages, they would wear a type of oilskin called a cirage, made from canvas soaked in linseed oil, rendering it waterproof.

During the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 19th century, new mechanisation and work processes exposed workers’ bodies to dangerous and gruelling tasks. They began to dress in tougher, more stain-resistant fabrics that were better adapted to their body shape so that their clothing would get caught or torn in the machines. This new workwear soon became an ‘all in one’ outfit, combining shirt and trousers, in the style of work overalls, which became the norm from the beginning of the 20th century. However, some workers made do with smocks for much longer. For example, despite their unsuitability, they were the standard outfit for silver ore miners at the Locmaria-Berrien Mine in 1839. They were also part of the first clothing allowance for workers at the Pont-de-Buis powder mill in 1845.

Initially, workers in the new factories of the Industrial Revolution were forced to put Breton society’s traditional code of honour to one side, “giving up traditional dress, unless strictly necessary,” was seen “as a renunciation of their culture, almost a degradation”, as Pierre-Jakez Hélias wrote in 1975 in Le Cheval d’orgueil. What’s more, the battle to get their employers to provide them with work clothes, instead of having to buy them themselves, was a long one. At the time, only state-run establishments offered clothing allowances. For example, in 1929, the Morlaix tobacco factory had 210 jackets, 240 pairs of trousers and 25 shirts made.

The uniformity of the work overalls worn by the workers and provided by the company contrasts with the foreman’s white smock, the engineer’s suit and the various outfits worn by the women, who were not provided with company work clothes.

A New Look

By combining safety, functionality and hygiene with ease of manufacture, clothing companies could guarantee both workers and companies the large quantities they needed, even though they were relying on factories in the north of France to weave and dye the fabric. From 1913, clothing brand Le Mont St Michel, originally established in Pontorson and later Rennes, catered for both industrial workers and rural, Breton-speaking workers, using advertising slogans such as “dilhad labour, dilhad nevez atao” or “dilhad labour, nevez bepred”, which can be translated as “Workwear: always like new !”

Other brands such as Le Glazik, Bonneteries d’Armor in Quimper (now known as Armor Lux), and Dolmen near Guingamp did the same thing. And every year since 1934, the master tailor’s atelier based in Brest harbour has made blue canvas jackets, trousers, and overalls for the dockyard workers, on top of the uniforms it makes for the French navy.

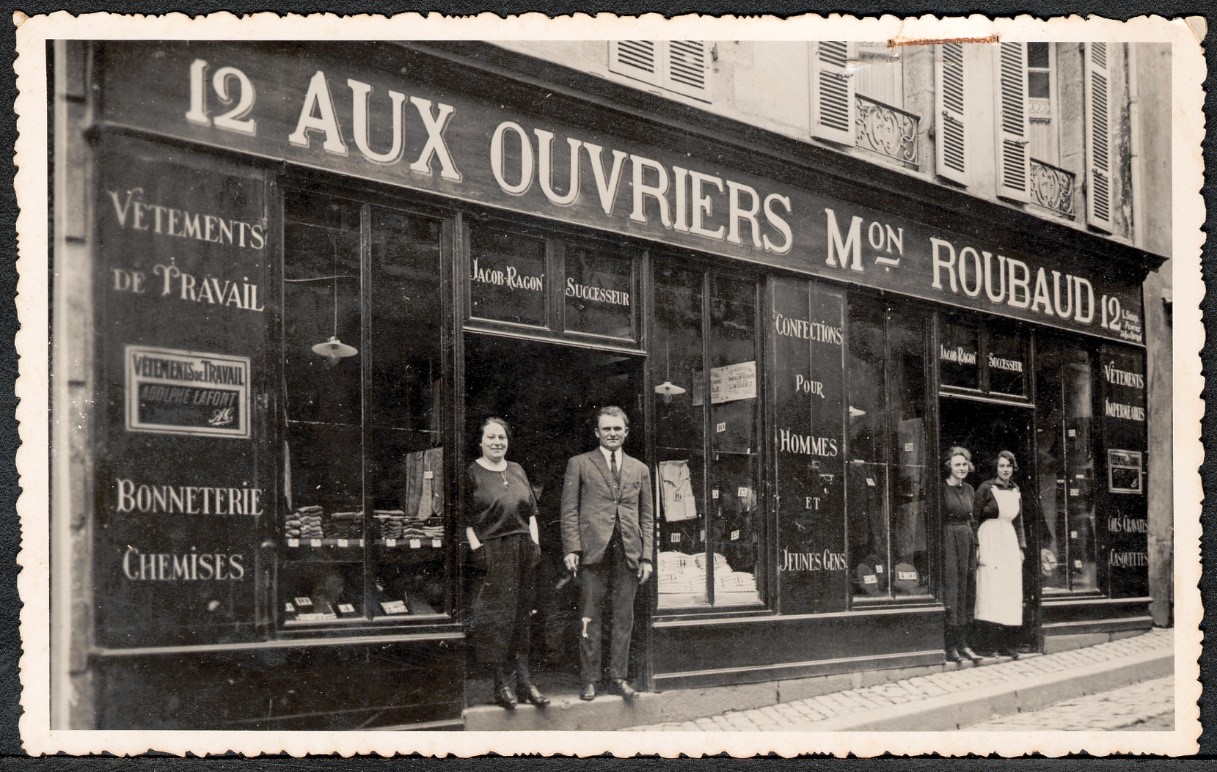

In 1898, in an advertisement published in the magazine L’Ouvrier du Finistère, the House of Roubaud was described as “a perfect fit for workers, thanks to its high quality products at modest prices, defying any competitor.”

Around the same time, in the 1900s, certain renowned clothing manufacturers with access to stockists in Brittany (Braillon, Belle Jardinière, Leconge et Willmann, la Manufacture de Saint-Étienne…) released machine-manufactured workwear. Thanks to their expertise in synthetic dyes, they were able to correct any naturally-occurring colour imperfections to create colours that remained stable wash after wash. Their design offices also continued to experiment with more resistant materials. However, this did not put either home-based or travelling seamstresses out of work; their stitching and patching skills remained invaluable for a long time, thus they withstood the costly purchase of ready-to-wear items.

Gradually, starting in the 1880s, styles representing particular professional groups began to develop alongside more individual looks: ‘working blues’ (as they were known), artisans’ aprons, schoolteachers’ smocks, carers’ tunics, office workers’ suits… The military-inspired uniforms of postmen and railway workers were an example for all to see of what the state generously provided its employees. Meanwhile, the tunics, trousers, rounded collar and képi (military cap) of senior administration agents leant an air of grandeur to the law enforcement authorities in towns and cities.

Workwear, A Language

When teachers and employees began to wear smocks, the sleeves of which were sometimes lined with a satin weave to protect them from dirt, another social dilemma was solved: that of how to present oneself. Teachers were given official instructions to dress “with decency and good taste”. “Cable girls” or “secretary stenographers” who “revealed their figures by not wearing smocks” were criticised for their lack of morals. What’s more, in factories and ateliers, the smock became a marker of hierarchy: only foremen wore white smocks. The symbolic potential of this did not go unnoticed by clothing manufacturers, who, from the 1960s onwards, began to make similar clothing to attract customers to their brand.

From Standard to Regulatory

In response to serious workplace accidents that occurred in Brittany’s agro-food industry, in the 1950s manufacturers began to make their employees wear finger cots, gauntlet gloves, steel chain mail and specially adapted aprons. These examples of protection for workers were the very beginnings of the development of personal protective equipment (PPE), which became regulation clothing in the 1990s.

From that point onwards, overalls, protective footwear, steel-capped boots, high visibility clothing, sleeveless jackets, helmets and protective gloves all became standard on state-financed construction sites and in factories, workshops, local authority maintenance units…as well as on fishing boats, factory vessels, container ships, etc.

An Old Look Repurposed

Starting in the 1950s, certain items gradually began to lose their professional clothing status, instead becoming social or identity markers outside of the context of the work environment. This was the case for the ciré, the marinière and the kab an aod (not to be confused with the English duffle coat) of the goémoniers from the Pays pagan (north-western coastal region between Plouguerneau and Goulven). For so long, these items had been worn by working fisherman and sailors, before being enthusiastically adopted by tourists, Breton music groups, artists and young urbanites keen to express their ‘breton sentiments’. More recently, a total renouncement of traditional work clothes has prevailed in some areas as a way for their wearers to express their outrage. In early 2020 in Lorient, Saint-Nazaire and Quimper, nurses threw down their tunics in protest against a pension reform, while in Saint-Brieuc, Nantes and Caen, barristers copied this action, declaring, “J’ai mal à ma robe” (“My robes are hurting.”)

Translated by: Tilly O’Neill