The 19th century in Brittany saw a decline in buckwheat cultivation. An extensive agricultural survey in 1866 indicates that potatoes had replaced buckwheat in many places, such as Pont-L’Abbé. During that same period, pioneers of the Breton folklore movement, such as Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué and François-Marie Luzel, recorded oral histories from rural Brittany that were gradually disappearing. Within this contradictory movement (disappearance/conservation), an emblematic space became established as one of the crucial markers of Brittany’s identity: the Crêperie (the pancakerestaurant)

One only needs to wander through the streets of Montparnasse, the prominent Breton neighbourhood of Paris, to find countless crêperies ! The colourful fronts of these restaurants bear names that explicitly refer to the Armorican peninsula. Crêpes and galettes are part of some of the main dishes of Breton gastronomy, alongside cider, strawberries from Plougastel and kouign-amann. These enduring dishes seem to refer to the heart of Brittany’s culinary tradition.

One only needs to wander through the streets of Montparnasse, the prominent Breton neighbourhood of Paris, to find countless crêperies ! The colourful fronts of these restaurants bear names that explicitly refer to the Armorican peninsula. Crêpes and galettes are part of some of the main dishes of Breton gastronomy, alongside cider, strawberries from Plougastel and kouign-amann. These enduring dishes seem to refer to the heart of Brittany’s culinary tradition.

Galette = pizza?

In fact, the story is much more complex. Undoubtedly, the « galette complète » - the classic ham-egg-cheese – seems to uphold all the virtues of tradition, especially when compared to those who do not hesitate to use ingredients as surprising as steak, fish, pineapple, reblochon cheese or even ketchup. Yet, whatever one may think of these curious mixtures, they demonstrate a dietary luxury that did not always exist. In the 18th century, the galette was mainly a sort of bread that was dipped in a gruel: no butter, let alone eggs or ham. Thus, one can better understand the common French language saying: « manger son pain noir » (eating your black bread), meaning going through a tough time.

During the last third of the 19th century, the folklorist Paul Sébillot referred to a curious recipe that appeared in the northwest of Ille-et-Vilaine: the “pain de Becherel” (bread from Bécherel). This invigorating dish consisted of a hot galette wrapped around an egg. In 1923, when the « Guide des merveilles culinaires et des bonnes auberges françaises » (Guide to the culinary wonders and good inns of France) passed through Brittany, it visited a crêperie in Quimper. However, the guide at the time only referred to butter crêpes with a glass of milk or a bowl of cider. It was not until much later, when meat consumption increased amongst the population, that ham was added to the “galette”, despite the “complète” being recognised today as an archetypal recipe. Once again, tradition is inseparable from its invention.

During the last third of the 19th century, the folklorist Paul Sébillot referred to a curious recipe that appeared in the northwest of Ille-et-Vilaine: the “pain de Becherel” (bread from Bécherel). This invigorating dish consisted of a hot galette wrapped around an egg. In 1923, when the « Guide des merveilles culinaires et des bonnes auberges françaises » (Guide to the culinary wonders and good inns of France) passed through Brittany, it visited a crêperie in Quimper. However, the guide at the time only referred to butter crêpes with a glass of milk or a bowl of cider. It was not until much later, when meat consumption increased amongst the population, that ham was added to the “galette”, despite the “complète” being recognised today as an archetypal recipe. Once again, tradition is inseparable from its invention.

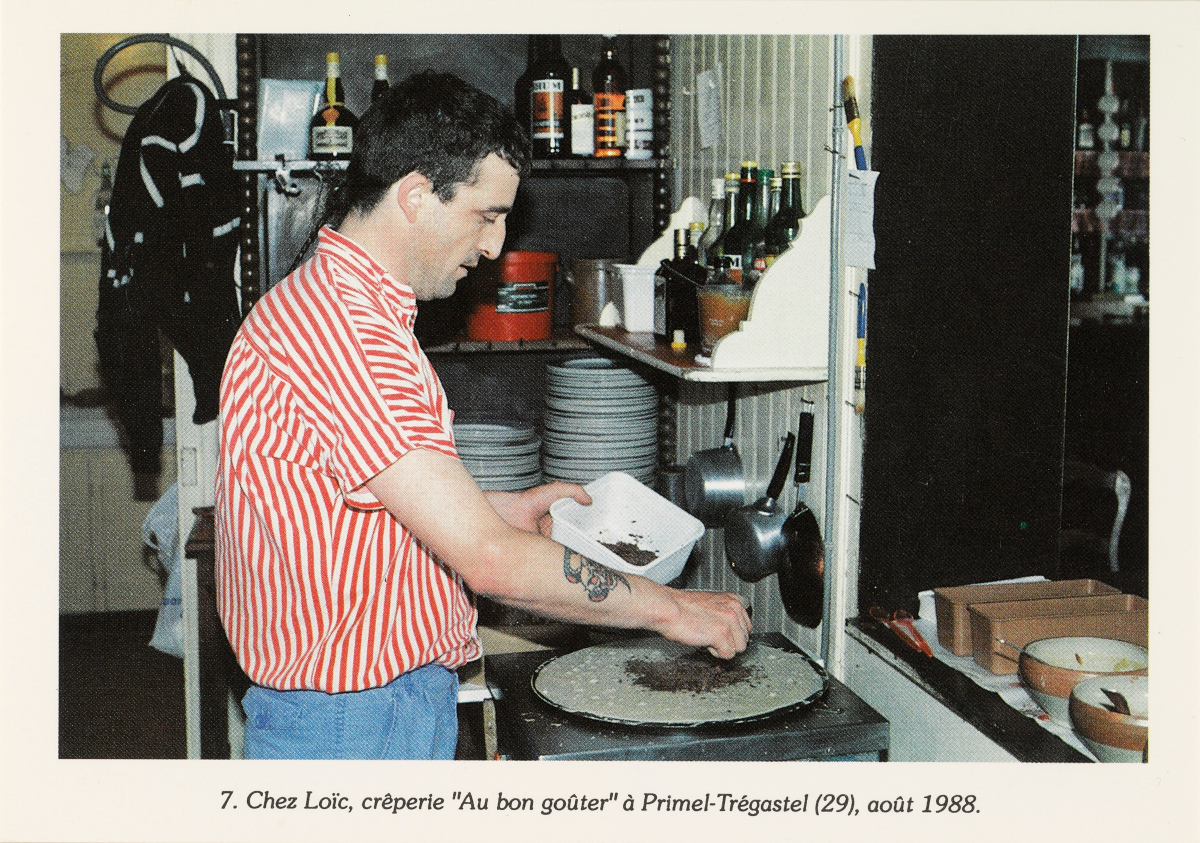

Inventing a restaurant

The crêperie is a fairly recent institution, but the crêpière or galettière cook, a predominantly feminine occupation, was first recorded at the beginning of the 18th century. For a long time, crêpes and galettes could be bought as takeout to be eaten at a tavern or an inn. However, it was in Rennes, on Beaurepaire street, that the first crêperie as we know it today was established. The restaurant was run by a certain “Poganne”. It was a real success, offering a menu financially accessible to almost everyone: “a penny for the galette, a penny for an egg, and to top it all off, a penny for extra butter”.

Despite these culinary changes, the essential features and role of buckwheat in Brittany is obvious. Undeniably, the plant is an integral part of today’s food culture and lifestyle. Indeed, has the 21st-century crêperie, in a way, not replaced the vital moment of conviviality that were the Breton evening gatherings of the 19th century?

Despite these culinary changes, the essential features and role of buckwheat in Brittany is obvious. Undeniably, the plant is an integral part of today’s food culture and lifestyle. Indeed, has the 21st-century crêperie, in a way, not replaced the vital moment of conviviality that were the Breton evening gatherings of the 19th century?