Travelling Traders

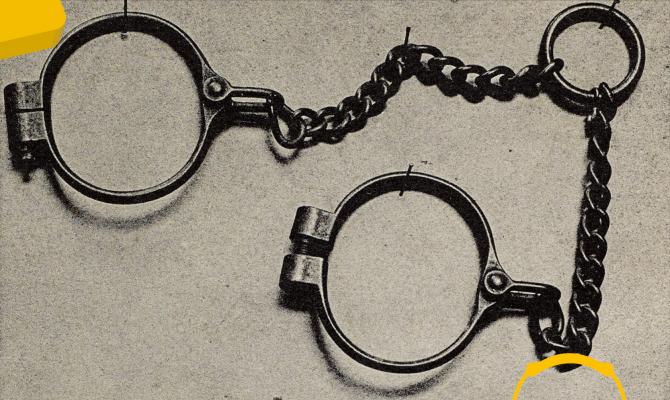

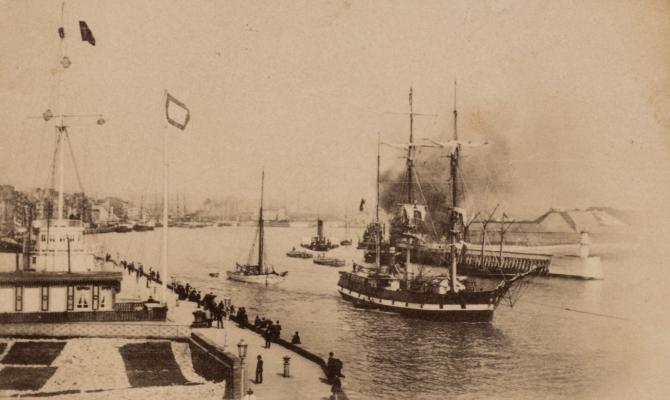

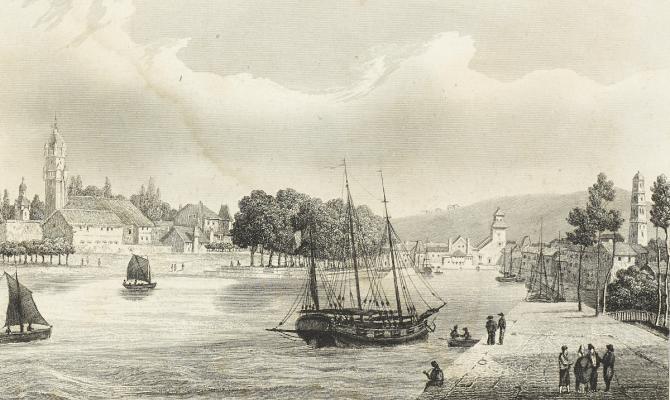

Brittany’s location on a peninsular at the heart of the vast Atlantic Ocean has made it a strategic point for sea voyages, both historically and in modern times. In the 15th century, Breton ships arrived in Bruges, delivering salt from the Guérande region, wine from Spain, and most importantly, fabrics from Brittany. Trade for this precious linen and hemp was in full swing. The little port of Landerneau was at the heart of exports of a fine-weave linen fabric known as crée, which was traded to the West Indies and South America. The darker side of this history is that Bretons participated in the triangular trade model, the basis for the slave trade between Europe, Africa and the West Indies. In the 18th century, Nantes even became the main slave trading port in France.

Setting Up Abroad

Though the majority of Breton travellers returned home, others decided to settle far from their native land. For example, Jean Brulelou, known as Brito, born in Pipriac in 1415, who left to practise his profession as a calligrapher in Bruges. This man from eastern Brittany (Haute-Bretagne) played a role in the beginnings of the print industry, which had been started 20 or so years earlier by Gutenberg, and he received Flemish citizenship in 1455. The discovery of America also opened up new horizons. Bretons went there to try their luck, in the hopes of better wages. Noël Le Goff or Le Got was one example. Born in Irvillac around 1674, he enlisted as a soldier as a very young man. He arrived in Canada and in 1698, he got married. The couple had 14 children, including nine boys to whom it is possible to trace back the surname Legault, which is extremely common in Quebec today. 600 Breton missionaries also arrived in the New World in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some were even recruited for their trilingualism (Breton, Latin and French), with the aim of converting the indigenous populations to Christianity.

Employment Emigration

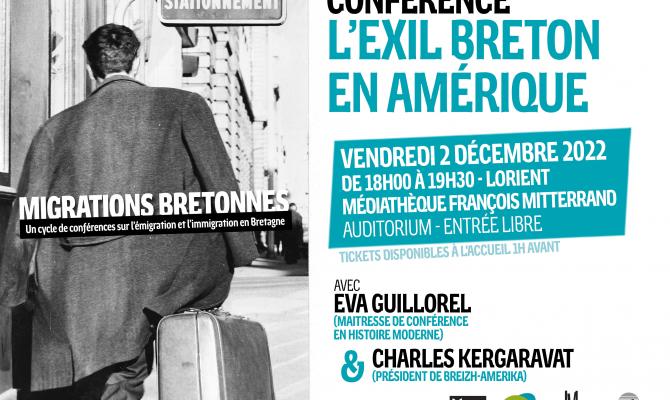

But these departures really only took place in dribs and drabs. It wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century that Brittany experienced a mass wave of emigration. Several hundreds of thousands of young men and women left the countryside, where there were too many workers. They settled particularly in Le Havre. In an 1891 census, more than 10,000 people were of Brittany origin, representing nearly 10% of the city’s population! The train also made Paris more accessible to many young people. Women took up jobs as servants in bourgeois households or as workers in the factories of Parisian industry, as did their male counterparts. But it was the American life that these young migrants truly aspired to. In 1901, the opening of a Michelin factory in New York prompted more than 3,000 Bretons from Gourin and Roudouallec to go and work there. Others left to open restaurants, taking advantage of French cuisine’s reputation.

Brittany’s (Small) Diaspora

Today, among the 3.5 million French people living abroad, it’s estimated that around 300,000 of them come from Brittany. There are therefore not all that many Bretons abroad, but they maintain very strong connections with their native land. Carhaix’s Vieilles Charrues music festival was even exported to Central Park in New York for festival’s 25th anniversary! Bretons may not be everywhere, but they remain highly visible in the places in which they do live.

Translated by: Tilly O'Neill