Bordeaux's Pascal Laporte brings rugby to Nantes

In 1907, when Pascal Laporte moved to Nantes for professional reasons, his rugby-player past was a huge endorsement. As Captain of the SBUC (Bordeaux University Rugby Club, Stade bordelais Université Club), he was one of the rare French players to have played for two years in Liverpool, UK, where he played Centre.

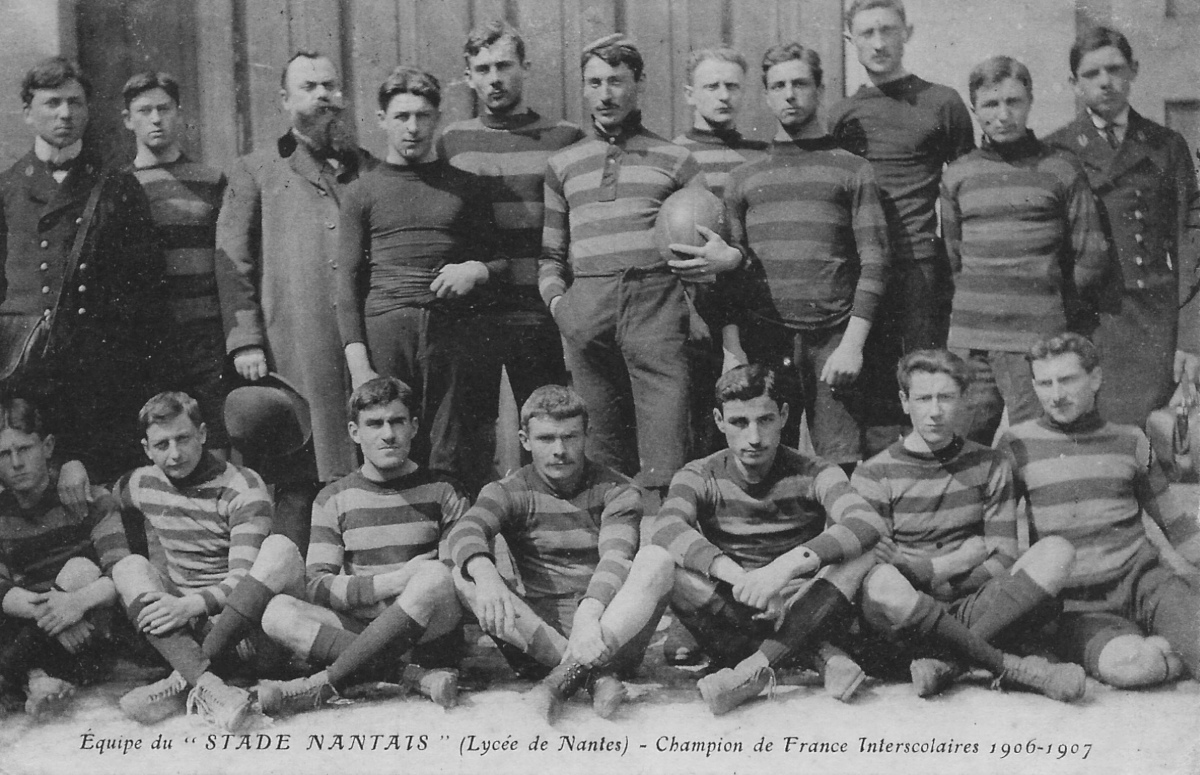

Rugby was already a fixture in the Nantes area thanks to Charles Bernard, an ex-international player, who also played for Paris’ Stade Français and founded the Racing Club de Basse-Indre-Couëron as well as the Lycée section of the Stade Nantais’ team - he himself had been one of the French inter-school champions in 1907. However, it was Pascal Laporte who was especially keen to develop the solid sporting institutions required for a rugby culture to take root in the area.

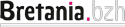

In 1909, he instigated the fusion of two Nantes-based rugby teams to form a new club, the SNUC, Stade nantais université club, and he would not rest until he had created a team to rival the very best. Several of his Bordeaux teammates – Henri Lacassagne, Augustin Hourdebaight, Hélier Thil – joined him in Nantes, as well as Welsh ex-international Percy Bush. “This team, unknown until two years ago, is currently one of the best in France,” wrote the Parisian newspaper Excelsior in December 1910, at a time when the SNUC was dominating the championnat de l'Atlantique organised by the USFSA (Union of French Athletic Sports Societies). A measure of the sports' success in the area, there were seven SNUC teams involved in the championship. The under-16 teams, as well as more seasoned players, helped to increase the generational range of players and indicated a growing interest in the sport. Other clubs were regularly being established and there were more than twenty teams in Nantes, home of the Dukes of Brittany, before the start of the First World War. Football paled into insignificance with just one club, the Club nantais d’association – created exclusively for the sport.

In 1909, he instigated the fusion of two Nantes-based rugby teams to form a new club, the SNUC, Stade nantais université club, and he would not rest until he had created a team to rival the very best. Several of his Bordeaux teammates – Henri Lacassagne, Augustin Hourdebaight, Hélier Thil – joined him in Nantes, as well as Welsh ex-international Percy Bush. “This team, unknown until two years ago, is currently one of the best in France,” wrote the Parisian newspaper Excelsior in December 1910, at a time when the SNUC was dominating the championnat de l'Atlantique organised by the USFSA (Union of French Athletic Sports Societies). A measure of the sports' success in the area, there were seven SNUC teams involved in the championship. The under-16 teams, as well as more seasoned players, helped to increase the generational range of players and indicated a growing interest in the sport. Other clubs were regularly being established and there were more than twenty teams in Nantes, home of the Dukes of Brittany, before the start of the First World War. Football paled into insignificance with just one club, the Club nantais d’association – created exclusively for the sport.

Le Parc des sports: built for rugby fans

The development of the sports sector and rugby’s success in particular resulted in the need for a new stadium which could offer spectators the best conditions for watching their teams play. Nantes Council, run by Paul Bellamy, granted the land known as the Champ de Mars to the Parc des sports company, in order to build a stadium and velodrome, including spectator stands, player changing rooms and shower blocks and even a reserved area for cut-price entry tickets.

The Parc des sports officially opened in December 1911, in the presence of the Oxford rugby team and a crowd of around 6,000 spectators. As part of his speech for the opening ceremony, Paul Bellamy explained the reasons for the new stadium: “Not only do we want to work towards developing Nantes as an artistic, intellectual, industrial and commercial hub, we also want to make it a sports destination and to show that we Bretons may have a reputation for being slow-minded, but we are tenacious and we will do what’s necessary to compete with the best.” Indeed, they pulled out all the stops to attract those living in Nantes. Schoolchildren could attend training sessions for free accompanied by their teachers, and 200 free places were reserved for them at every match. “They are spectators now, but they will be players later”, claimed Eugène Doceul, Managing Director of the Parc des sports, in local newspaper Le Phare de la Loire. Banners around the city announced upcoming rugby matches and entry prices were adapted to reflect the social diversity of the spectators. But it was difficult to measure the size of the crowds in the stadiums. Figures published in the press were always round numbers. Articles from sports commentators regularly emphasised the spectators’ support for local teams and their enthusiastic cheering at certain action-packed points during games, and they nick-named fans ‘braillards’, or ‘howlers’.

The Parc des sports officially opened in December 1911, in the presence of the Oxford rugby team and a crowd of around 6,000 spectators. As part of his speech for the opening ceremony, Paul Bellamy explained the reasons for the new stadium: “Not only do we want to work towards developing Nantes as an artistic, intellectual, industrial and commercial hub, we also want to make it a sports destination and to show that we Bretons may have a reputation for being slow-minded, but we are tenacious and we will do what’s necessary to compete with the best.” Indeed, they pulled out all the stops to attract those living in Nantes. Schoolchildren could attend training sessions for free accompanied by their teachers, and 200 free places were reserved for them at every match. “They are spectators now, but they will be players later”, claimed Eugène Doceul, Managing Director of the Parc des sports, in local newspaper Le Phare de la Loire. Banners around the city announced upcoming rugby matches and entry prices were adapted to reflect the social diversity of the spectators. But it was difficult to measure the size of the crowds in the stadiums. Figures published in the press were always round numbers. Articles from sports commentators regularly emphasised the spectators’ support for local teams and their enthusiastic cheering at certain action-packed points during games, and they nick-named fans ‘braillards’, or ‘howlers’.

The crucial role played by sports columnists

As daily newspapers began to include and develop sports columns, especially Le Phare de la Loire and Le Populaire, a new category of journalists appeared: sports columnists. Not many would include their names on their articles, but they published match summaries which reveal a good command of the rules of play. “We will do our utmost to hold the interest of those who do not see these words as pointless,” wrote the sports columnist for Le Phare de la Loire when announcing the new rugby season in Nantes. The term ‘football’ was used at the time for rugby, and association was used for football. Sports journalists would usually express themselves in the first person singular, and would clearly express their opinion on a match, a team, the players, the referee and the spectators.

Because of how much it printed about sport, and more particularly about rugby during the winter sports season, the press contributed to giving an air of respectability to a sport which was often criticised as being violent. In Nantes, rugby continued to thrive during the First World War and in the post-war period. Such strong roots confirm that Nantes was most definitely a home to rugby before the city experienced any sign of football mania.

Because of how much it printed about sport, and more particularly about rugby during the winter sports season, the press contributed to giving an air of respectability to a sport which was often criticised as being violent. In Nantes, rugby continued to thrive during the First World War and in the post-war period. Such strong roots confirm that Nantes was most definitely a home to rugby before the city experienced any sign of football mania.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill