Often associated with one another, flax and hemp share the same biological structure. The flax Linum Usitatissimum is a herbaceous plant for producing oil and making textiles, with blue flowers. However, other varieties do exist, with white, red or yellow flowers. Hemp (cannabis sativa) is also a herbaceous plant, belonging to the same group as recreational cannabis. The complimentary way in which the spun cloth from these two plants was used highlights how much they had in common : flax for light clothing and house linen, Hemp for rope, work clothes and ship sails.

Without a doubt, it is the historian Jean Tanguy who paved the way in showing the importance of these plants for the Breton economy, with his research beginning in the 1960s, focusing on the Golden Age of manufacturing, from the 16th to the 18th century. He has since captured the interest of other historians and enthusiasts, enabling them to widen the area of research from where it had begun, in and around Morlaix.

In Brittany, both its maritime climate and its fertile soil render the cultivation of these plants favourable. The North Coast, with its areas of lime soil, was especially suited to the growing of flax, whereas hemp, which has less specific requirements, grows everywhere else. The subject in question is the domestic production of canvas produced for commerce and exportation, manufactured under strict laws, and found under a plethora of names: known as crées, graciennes , or pedernecq, landerneaux or even plougastel and bretagnes in Côtes-D’Armor. The hemp canvas was called olonnes around Locronan, and noyales in Noyal-sur-Vilaine. We will focus on this particular production of flax.

In Brittany, both its maritime climate and its fertile soil render the cultivation of these plants favourable. The North Coast, with its areas of lime soil, was especially suited to the growing of flax, whereas hemp, which has less specific requirements, grows everywhere else. The subject in question is the domestic production of canvas produced for commerce and exportation, manufactured under strict laws, and found under a plethora of names: known as crées, graciennes , or pedernecq, landerneaux or even plougastel and bretagnes in Côtes-D’Armor. The hemp canvas was called olonnes around Locronan, and noyales in Noyal-sur-Vilaine. We will focus on this particular production of flax.

Breton flax and importation: from the Baltic to Roscoff

Important quantities of flax seed were imported from the Baltic, arriving in the port of Roscoff. Ships from the ports of Libau, Windau, Riga, Memel and also Königsberg, unloaded their cargo of 80 kg barrels in springtime, after around three months at sea. The seed is then redistributed, usually by navigating along the Breton coast, to other ports. The cargo passing though Breton ports is considerable: in 1757, 1,368 tons were unloaded from 14 different ships.

Although Brittany could indeed produce its own seeds, the importation of seed could be justified by the need for renewal. Grown in spring, this plant likes to be in a good depth of well-prepared soil. Flax does not need a lot of either fertilizer or pesticides, however, it drains the soil of nutrients. It is the head crop in a a six or seven year rotation. It flowers a hundred days after being planted. The most common, the little blue flower, does not last long. It opens in the morning, and has dropped off by the afternoon. However, another flower appears immediately on the stem, and the plant remains in flower for about ten days. These magnificent fields of blue flowers swaying in the breeze are a sight to behold!

Although Brittany could indeed produce its own seeds, the importation of seed could be justified by the need for renewal. Grown in spring, this plant likes to be in a good depth of well-prepared soil. Flax does not need a lot of either fertilizer or pesticides, however, it drains the soil of nutrients. It is the head crop in a a six or seven year rotation. It flowers a hundred days after being planted. The most common, the little blue flower, does not last long. It opens in the morning, and has dropped off by the afternoon. However, another flower appears immediately on the stem, and the plant remains in flower for about ten days. These magnificent fields of blue flowers swaying in the breeze are a sight to behold!

A complex but well thought out transformation.

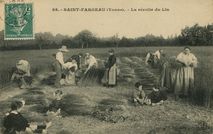

To obtain the longest fibres possible, the plants are pulled by hand in a process made up of different stages that require a considerable amount of water and manpower. These stages were undertaken by farmworkers who welcomed the extra income. The retting, the first preliminary stage before separating the fibres of the central stem, took place in the « Poullin », a rudimentary water hole, in the Léon area, and in pools called « rottoirs » in the Trégor area. This was prohibited in open water, due to the pollution it engendered. Today, this process is done « in the field », the bundles of hemp are laid out on the ground, and are frequently turned , in order that they may come into contact with ground dew. The sheaves are then dried before the plant fibres are separated, enabling the stem fibres (anas) to be set aside for grinding and combing. The rough threads are then given to the spinners, who use a large spinning wheel,a common sight in every household at the time. The job of spinning, done essentially by women, only appears in official pay registers from the second half of the 18th century.

The differences in production are notable between the territory of « Crées » and that of « Bretagne ». In Léon, the mixed fibres are whitened in a « kanndi » ( a washing pool), whereas around Quintin, it is the canvas itself which is whitened.

The production of good quality canvas

The weavers, who are always to be found in a region with a high percentage of humidity, are the next link in the production chain. This humidity protects the thread from breaking. The weaver could work at home, on a merchant farmers property, or from the end of the 18th century onwards, in workshops fit for purpose. The invention of the flying shuttle simplified this tedious task a little. Length, width and quality are tested by Trading standards regulations which control and police production in general. Canvas makers had to follow the same regulations.

The bundles were then transported to trademark offices on the ports whose purpose was export, in Landerneau, Morlaix, Saint-Brieuc, Saint-Malo, Nantes, Vannes and Lorient, under the clerk employed by one particular negociant. After the work of the weavers and the canvas makers, the official seal of the Canvas Quality control office is stamped on the product, before it is embarked on the awaiting ship, together with products from the local tanneries.

The prosperity that was generated by the production and sale of canvas has left its indelible mark on the Breton landscape. Apart from the local culture linked to the work of the local farmers, the imposing habitations built by merchant farmers are an outward sign of the opulence that came from this flourishing economy. In the ports, a number of buildings that belonged to the negociator- ship owners are a lasting reminder to this prosperity also. Even to this day, we have conserved the Parish enclosures, numerous in this production area.

The prosperity that was generated by the production and sale of canvas has left its indelible mark on the Breton landscape. Apart from the local culture linked to the work of the local farmers, the imposing habitations built by merchant farmers are an outward sign of the opulence that came from this flourishing economy. In the ports, a number of buildings that belonged to the negociator- ship owners are a lasting reminder to this prosperity also. Even to this day, we have conserved the Parish enclosures, numerous in this production area.