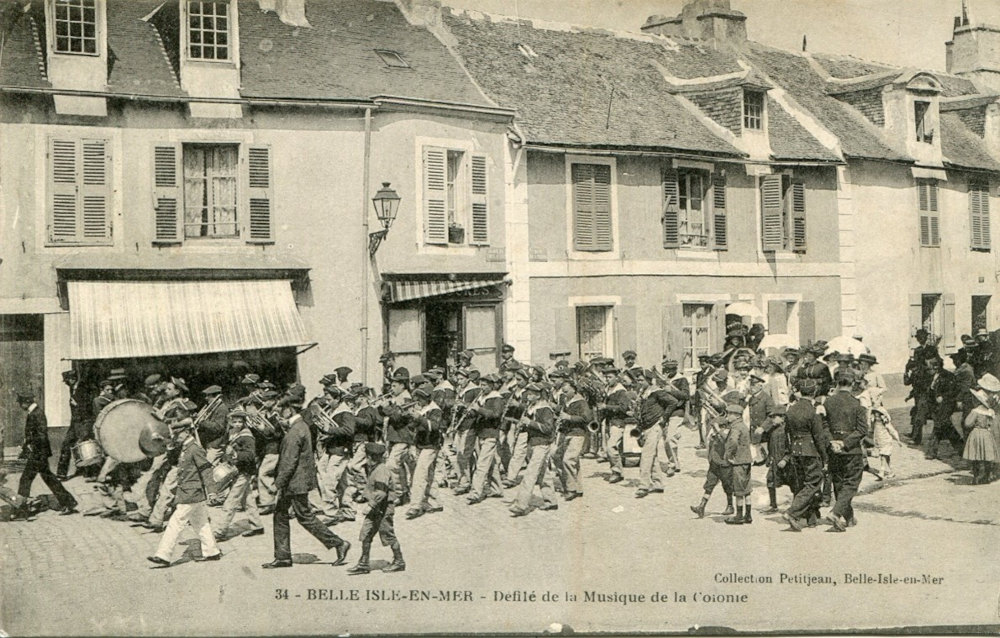

As the 19th century transitioned into the 20th, no local celebration was complete without a marching band. All across the country, musical groups brightened up Sundays in springtime and were the highlight of summer events. Anxious to reassure people of the merits of its correctional programme, the prison service was careful to ensure each of its facilities had its own marching band. The main aim was to offer wards with musical talent choice places in the military marching bands of the different barracks they would be sent to upon their release. At Belle-Île-en-Mer, the ‘fanfare’ was created as soon as the establishment opened. It followed classic military tradition (drums and brass instruments) and at the start of the 20th century it widened its range, acquiring several clarinets and a double bass. A petty officer was in charge.

Reviews from the local press at the time tell us just how successful the Belle-Île marching band was at veiling reality. Although almost all articles written about the institution conjure negative images (escapes, mutinies, altercations with the locals…), those relating to the establishment’s marching band are on the contrary very positive. During the summer of 1895, the band was part of celebrations at Port-Navalo (56). Newspaper L’Avenir du Morbihan was delighted with their performance: “We owe a special mention to the young musical wards of the Belle-Île penitentiary, who certainly added a great deal of charm to the day’s events. It was an inspired choice of the island establishment’s kindly director to surprise us with a concert. Our compliments to the young musicians.” Two years later, the marching band were treated as real stars when they opened the velocipede race in Vannes. “At two O’Clock and to a two-time rhythm, full of brio and boisterous energy the musicians set the pace as they entered the velodrome, followed by a huge crowd, before taking up their place on the grass next to the jury stand.”

The music made people forget the reality, instead persuading the cheerful and receptive spectators that the prison service had successfully achieved a correctional programme that would transform young criminals into musical virtuosos. However, when they went back to Haute-Boulogne, the musicians would return to their cell-like dormitories, and the everyday exhaustion and mistreatment they had grown so used to.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill