An ancient tradition

A charter from 1514 at Beauport Abbey attests to Brittany’s fishermen travelling to the shores of Newfoundland well before this date. On the eve of the Revolution, there were twelve cod fishing vessels from Paimpol working off the Newfoundland Grand Banks.

In 1793, the French Revolutionary Wars put a stop to this activity, with some ship-owners temporarily renewing their commerce raiding ties.

Fishing voyages began again in 1816 but in 1835, with more than 500 men regularly sent out to fish, catches began to diminish and the people of Paimpol feared for their Newfoundland yields.

At the time, Paimpol was a town of no more than 2200 people, but it was home to one of the two biggest maritime districts in France. And since their creation in 1824, the city had also been home to one of the six French schools of hydrography, which later became schools of navigation and then national Merchant Navy academies.

Time for a change

In Newfoundland, the increasing scarcity of its main export and the gradual decrease of privileges at one stage accorded to French fishermen now prohibited fishing in coastal waters.

Brittany’s ship-owners could no longer justify such large-scale voyages for such mediocre returns.

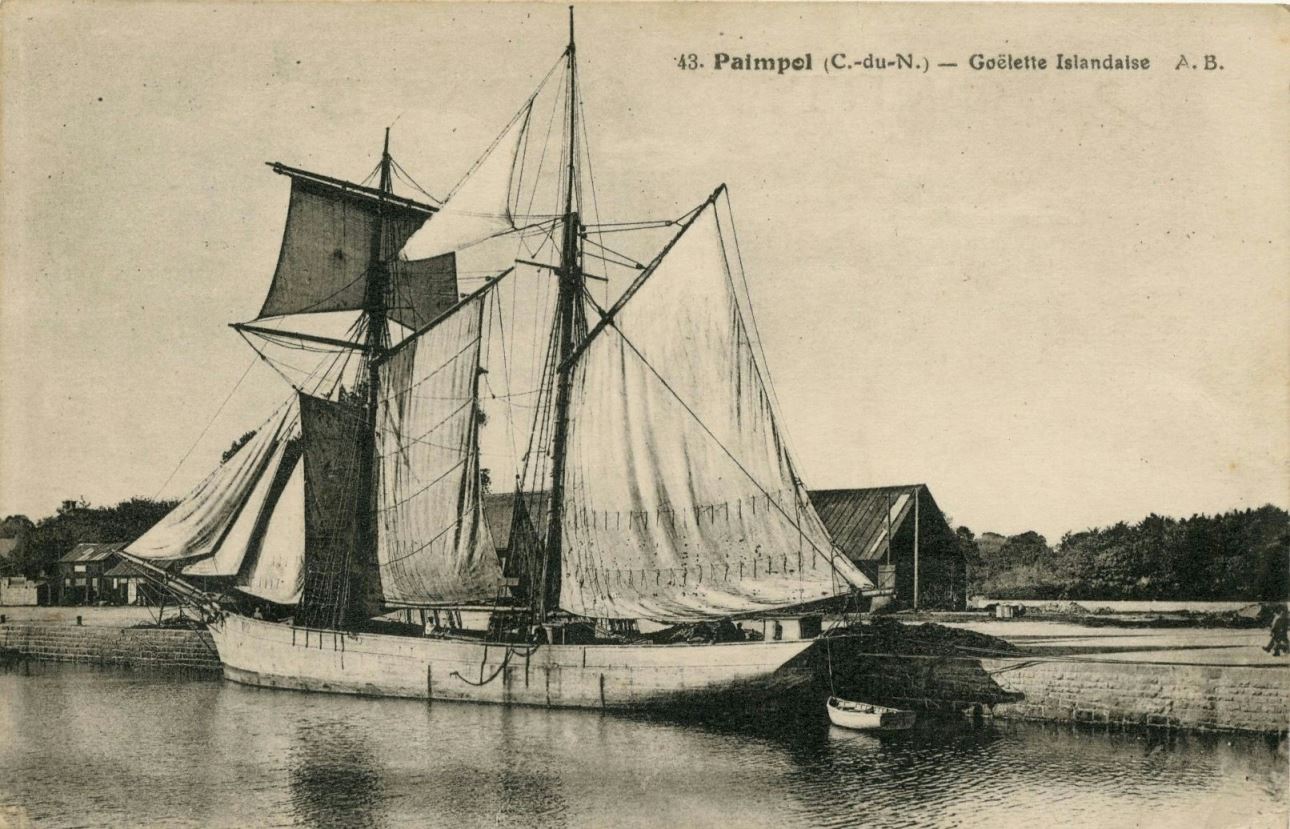

The boats headed to Newfoundland (known as terre-neuvas, the archetype of which was a three-mast schooner with could carry up to 500 barrels) required a crew of 40 men the journey to the Grand Banks took anything between 20 and 45 days at sea.

The topsail schooner, which could carry between 100 and 180 barrels, required fewer men and could reach Iceland within a week. A change in destination therefore became the obvious solution.

The Icelandic period

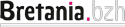

In 1852, ship-owner Louis Morand (1806-1860) took inspiration from the people of Dunkirk and sent his ship L’Occasion to Iceland. This adventure was the start of 80 hugely economically beneficial years for the people of Paimpol, but at a great cost, including the loss of 2000 men and 120 ships.

Other ports on France’s northern coast followed this example, but it was most certainly Paimpol which gained the most from the Icelandic period, thanks to the quality of its shipbuilding and the development of industry, craftsmen and related businesses.

At its height in 1895, Paimpol was home to 80 Icelandic schooners and four terre-neuvas.

A new fishing strategy

In Newfoundland, the fishermen had employed a sedentary hook and line fishing technique.

The anchored terre-neuvas would deploy Dory rowing boats, each with a crew of two: a captain and his shipmate. They would put out their lines in the afternoon and bring them in the next morning at dawn. Unless a change of location or maintenance work was planned, the rest of the day would be devoted to cleaning the fish and preparing the lines for the next day.

In September/October, the terre-neuvas would return to France loaded with between 150 and 300 tonnes of cod, sometimes more.

But off the coast of Iceland, where the sea was deeper and the storms less merciful, it was impossible to use the same boats and fishing strategy. The fishermen needed smaller vessels which could react quickly in the face of sudden and violent weather changes, and from which they could adapt to an on-board ‘roaming’ fishing technique.

After the traditional Icelandic Pardon ceremony, the flotilla (each schooner had a crew of 20 to 25 men) would cast off mid-February for a period of 6 to 8 months.

In order to catch the cod, the sails were brought in to create a slow, lateral drift. The men would spread themselves out along the ribband, each equipped with a heavily weighted line which they would let out according to the depth of the shoals. Each man was paid according to the number of tongues extracted from his catch.

In mid-May, at a predesignated fjord, the schooners would transfer the first catch to the hold of waiting planes that would bring with them post, supplies, a salt restock and new equipment so that the second catch could get underway. The planes would then compete to be first to deliver the catch to their final destinations, therefore achieving the highest price for this very popular fish. They were rarely headed for Paimpol.

Social and economic impact

Though there was diversity in the types of fishing vessels used at the start of the Icelandic age, these were rapidly replaced by a fleet of topsail schooners which were upgraded in Paimpol to prepare them especially for their Icelandic trip.

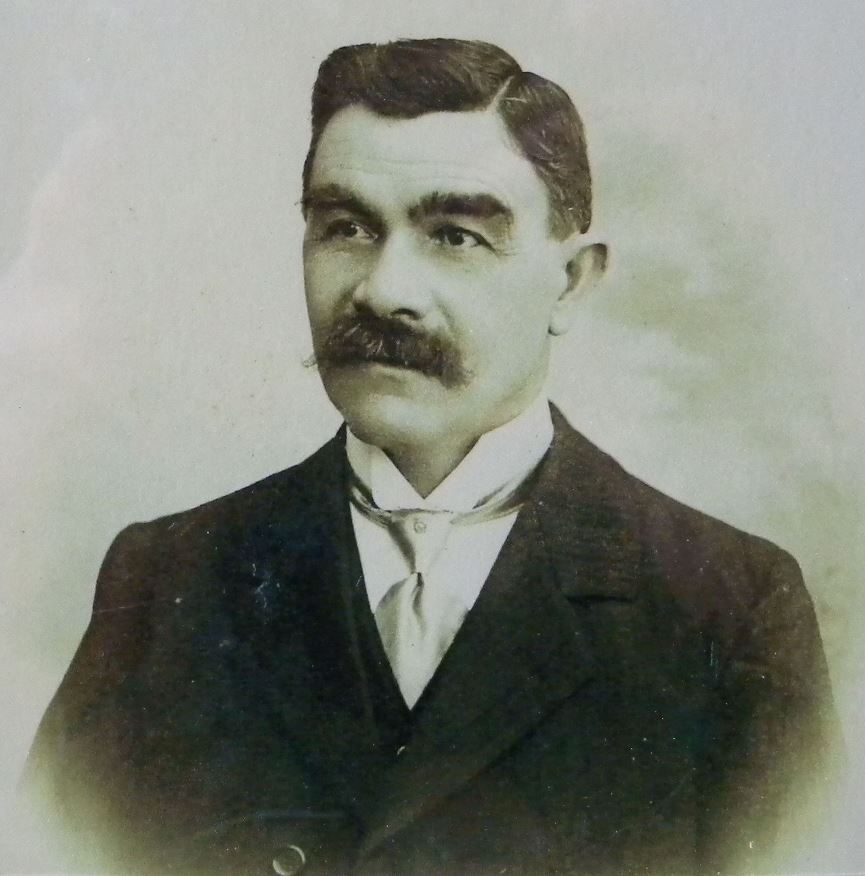

Paimpol shipbuilders had until that point only produced these vessels in small numbers. In 1860, a young master carpenter, Louis Laboureur, joined and grew his father’s company by improving the form and other singularities of this fishing schooner.

He took on Émile Bonne as foreman in 1890, who then took over the company before starting his own business in 1899 in Poulafret. His became the biggest shipyard in the area. Thanks to a further dozen or so others (Perrot, Pilvin, Goasdoué, Le Chevert), over 800 labourers were employed within Paimpol’s shipbuilding industry.

Other companies were also part of this industrial boom. These included the Quément, Tréhiou, Gobert and especially Dossmann (inventor of the topsail and roller reefing gear) forges; reputed sailmakers L’Helias-Gleyo, Rivoallan, Le Caër, Rochut; pulleymakers; rope factories; fishing industry manufacturers; and many other craftsmen and businesses, such as clothing manufacturers, shoemakers, salt preservers, cider brewers and biscuit factories all provided the supplies and equipment the men and boats might need for seven or eight months at sea.

The final years

After reaching its height at the end of the 19th century, the tradition barely survived the First World War. A sudden surge in voyages in the 1920s just as quickly fizzled out. The Icelandic law of 21st April 1922, regulating access to its territorial waters in order to preserve its production and fishing grounds, prohibited the transfer of the first catch to planes. Any hopes of reigniting the industry vanished. Technical progress, the dawn of the trawler, and poorly adapted port infrastructure all led to the final Icelandic voyage in 1935, as La Glycine closed this intense and very harsh period.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill