Different morphologies

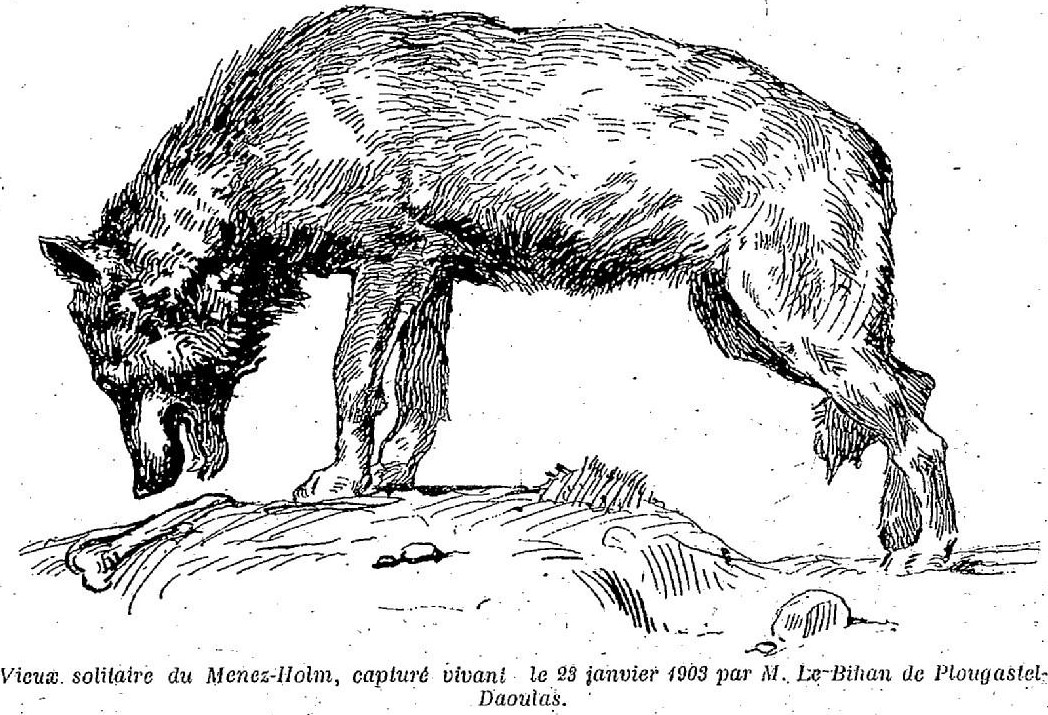

The colour and size of grey wolves (Canis lupus, Linné, 1758) can vary greatly, highlighting the species’ ability to adapt. An adult wolf weighs between 25 and 65 kilos (35.8 kilos on average for males and 28.1 kilos on average for females), and can measure up to 2.5 feet (75cm) at withers. In 1892, a wolf weighing 82 kilos was killed in France’s Nièvre region. A grey wolf’s coat is predominantly a mix of tan and black, but other grey to cream colour variations exist, with large white markings, particularly around the neck, jawline, underbelly and interior leg areas. The coats of specimens preserved in Brittany range from a very light tan (History, Archaeology and Heritage Museum (musée de la Société polymathique), Vannes; Natural History Museum, Nantes; Rennes 1 University Museum) to very dark (several stuffed heads from private collections).

An ever-present and opportunistic predator

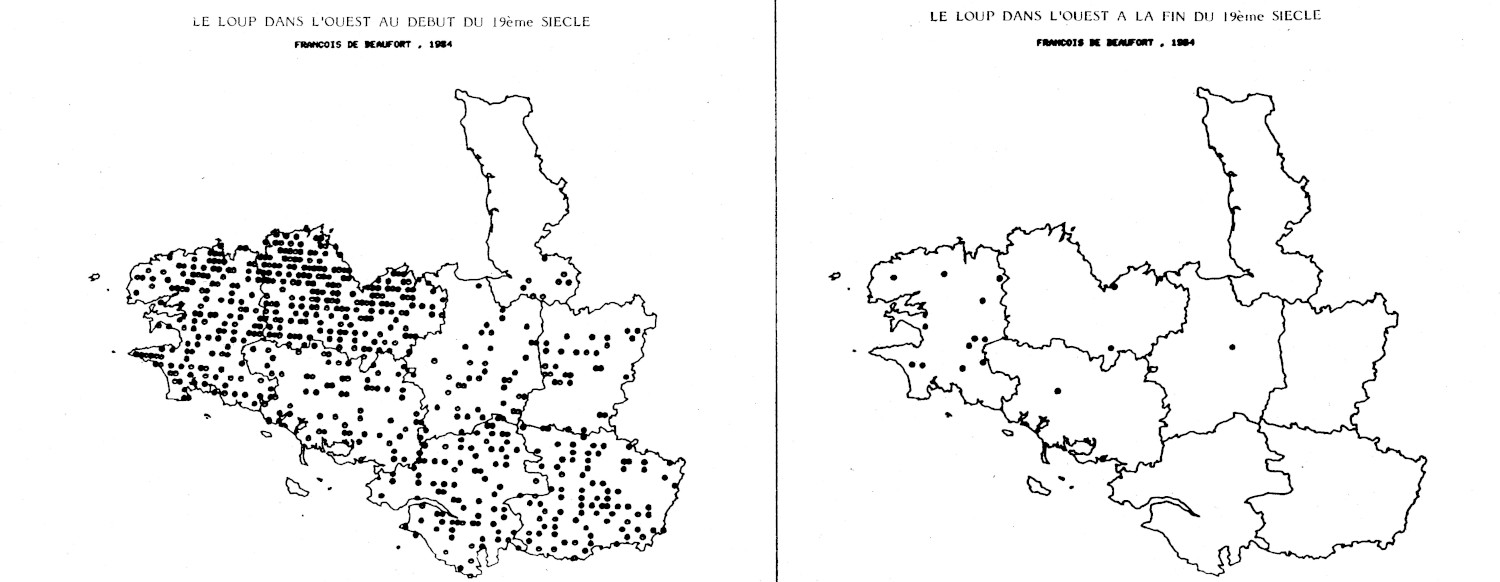

Maps recording the premiums paid for helping to wipe out the wolf population (see map) reveal that localities with a high percentage of moorland terrain received the highest remuneration. Coastal areas were also beneficiaries. Only particularly mountainous forest areas with thick woodland were a safe, if temporary, refuge for wolves.

A reasonable estimate of the adult wolf population in France around 1800 was between 5,000 and 6,000, minimum. Official and unofficial culling operations served to control their rate of natural increase. There were around 600 wolves spread over Brittany’s five departments. The Finistère region, with its plentiful moorlands and woodlands, was home to between 200 and 300 individuals.

The wolves’ preferred prey in Brittany is clear from accounts of the time. Both traditional folktales and stories of real life make the same observation, establishing dietary preferences. Horses and sheep are at the top of the list, followed by pigs, cows, goats and dogs. Attacks on livestock were common occurrences and could result in severe local losses, especially in the case of sheep, despite constant surveillance (cows and horses were much better able to defend themselves).

But since people knew how to protect their livestock, the wolves’ diet was based mainly on smaller prey and carrion. Bigger prey was rare and, unlike in other areas, there were no wild herds to act as a nutritional mainstay.

Wiping Out the Wolves

The people of Brittany were not afraid of wolves; from a young age, they were taught that wolves were fearful animals that you simply scared away by making noise. This was the idea behind the “hue du loup” or “wolf cry”, which signified a wolf’s presence. A ‘huchée’ was a distance of around one and a quarter miles: the furthest distance a shepherd’s voice (or the sound of their horn) would carry.

A general call for the destruction of the wolf population prevailed. The most effective way to contain the population was to cull the pups. Some shepherds knew how to find the pups in order to cull them and receive a premium. The process, known as ‘huchage’, consisted of mimicking a wolf cry in order to get a response and locate the litter.

People also used wolf pits, some of which were made with drystone walls and could be extremely deep. Despite their limited success, people also used traps. For example, in 1708 at Cléongar farm in Plabennec, they used an “iron grid with a wolf snare”. Official ‘Wolf Catchers’ were in charge of wiping out the wolf population, but hunting wolves with friends was an enjoyable pastime and so they limited their official activities in order to preserve the species.

All these activities helped to contain the wolf population despite the species’ high birth rate. Human population increase, the use of strychnine and considerable premiums all contributed to their extinction, but it is important to remember that this was within the greater context of the general degradation of moorland areas.

The last wolves were seen in various parts of the region between 1885 and 1906. It should be noted that the extermination of wolves has led to an increase in the population of smaller carnivores, in turn accentuating the problems caused by the latter.