Both in the countryside and on the coast, women improvised as best they could for a long time. It’s often said that the only raincoat available was a hessian sack with two corners folded into each other to create a hood. The women who unloaded the boats in the ports of Loctudy and Pont-l’Abbé between 1914 and 1918 would also cover their shoulders to combat the pressure of the loads they were carrying. This thick fabric was key to the manufacture of one particularly ubiquitous item: the apron, which was worn with a justin (jacket) and trousers. To protect themselves from the heat or the cold, they would knot a scarf under their chins and wear a wide canvas hat, the brim of which hung down over the shoulders to protect the back of the neck.

In the factories

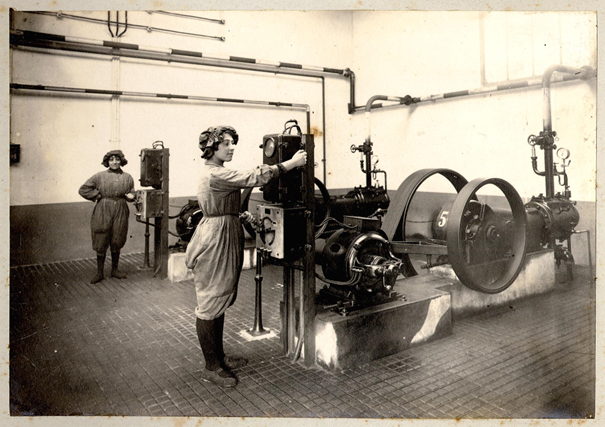

During the Industrial Revolution, which attracted a large part of the rural workforce to the cities, women continued to wear these ‘rags’ for some time, especially since the general consensus was that the female workforce should not be granted workwear. But feeling the need for garments distinct from their ordinary clothes that would be slightly more fit for purpose, they began to wear work coats. These had been developed from the smocks worn by farmworkers and artisans and were made from a very tough, dark material, their length in keeping with general views on women’s modesty. It had a belt and the sleeves could be tightened at the wrists with either buttons or laces to keep the fabric from being caught in machines. The collar offered enough freedom for women to personalise their outfit.

The need to display one’s identity in a way that combined functional utility led women workers at the Douarnenez canning factory to wear the penn sardin coiffe (headdress). This choice was an extremely pragmatic one: the coiffe kept your hair off your face and out of your eyes whilst allowing you to move your head freely; it was made from the cut-offs of inexpensive fabrics, which could be washed and dried quickly, and therefore often so as to avoid becoming too encrusted; finally, the shrewd mix of cotton and lace used to make them helped to maintain the appeal of a coiffe which had been previously used by the women’s rural forebears as a regional emblem.

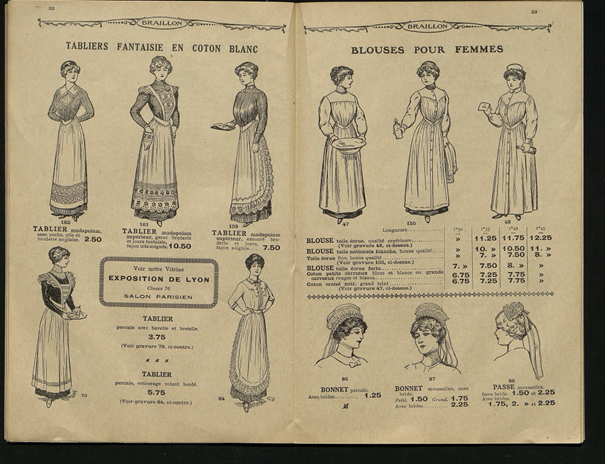

Today’s equivalent, the hairnet, is disposable, meeting with strict hygiene regulations. In addition, tunics, gloves, ear protection and aprons are provided by the company. This is an important change, since for many years men and women in every industry had to buy their own work clothes with their own money. Likewise, women were not really able to consult catalogues, since clothing manufacturers catered to male standards, offering a bare minimum of ‘ladies aprons’ and ‘ladies smocks’.

Clothing as a marker of community

At the end of the 19th century, many women had to liberate themselves from the clothes worn by the nuns who had preceded them in their roles. The smock was key to this.

With descriptions, price and size explanations, the catalogue offers “smocks for women” and aprons, and also includes laundering recommendations for its female customers: “Never iron a brand-new smock”, “Do not wear too long without washing”, and also “Never apply soap directly to the smock.”

In the service industry, women typists and telephone operators agreed to wear smocks at the start of the 20th century. It protected them from the ink stains they would get on their sleeves from typewriter ribbons, as well as from the ink pens they used for shorthand. In the mixed sex environment they worked in, the smock hid their skirts, stockings, blouse and figure, which guarded against inappropriate comments from their male colleagues. It warded off the jeers directed at those who were sometimes accused of revealing their figures when they removed it.

Urged by their employers to ‘dress with decency and good taste’, schoolmistresses initially began to wear long black dresses, a typically discreet clothing option. Later, they wore smocks which obscured any hint of hierarchy, length of service or rank. In the 1920s, their wardrobe was made up of lighter-coloured skirts (with a white blouse), worn with grey stockings – as long as these weren’t transparent – underneath a grey coat.

Similarly, the long smock worn by the first female nurses removed any aspect of individuality. The need for hygiene imposed clothing that covered up as much of their bodies as possible. Their smocks had to be disinfected, changed and washed every day. They were washed at 90 degrees, a temperature that can only be withstood by non-dyed cotton, therefore favouring the colour white. After the Second World War, the arrival of synthetic fibres which did not shrink or lose their colour at high temperatures allowed for greater comfort, easier maintenance and a greater variety of colours.

Starting in the 1960s, the tunic-trouser combination manufactured using a polyester-cotton mix gradually replaced the dress-apron, which nevertheless remained the staple in nursing schools.

Fashion: an unchanging measure of women’s workwear

For a long time, people aimed to reassure women of the ‘inherent elegance of their sex’ as described by Parisian seamstress Madame Commard in 1916, who registered a patent with the French Patent and Trademark Office for a truly feminine garment called La Françoise.

It was exactly this type of all-in-one outfit that the Pont-de-Buis powder mill chose to dress its women workers in, after recruiting them to make gunpowder and explosives when their male workers were called to the front. The 3,500 woollen overalls ordered by the company in 1917 were fireproof; their wide, short cut could be tightened at the waist with a belt and closed at the wrist to avoid the introduction of toxic powders. The overalls had buttons and therefore couldn’t be put on over your head, where, despite a large hat, deposits of dangerous substances collected in their hair risked ending up on the workers’ skin. In truth, this outfit was inspired by the fashionable jupe-culotte from Béchoff-David which had been worn at Auteuil racecourse before the war. Paradoxically, from 1917 it also became a symbol for the struggle for better pay by female armament factory workers, who marched on the streets of Paris in their work ‘uniforms’.

In Pont-de-Buis and in Toulouse, women workers wore the same overalls, chosen by the company for their ability to protect them from the toxic substances that were released in the ateliers.

Made by women

Once male workwear began to appear, many seamstresses became a part of the making process. This work was one of the few ways traditional society allowed them to earn money. They either travelled from farm to farm with their sewing machines, or they were employed by manufacturers directly. The latter were very aware of the huge untapped resource of female workers in rural Brittany.

From 1913 in Rennes and Pontorson, the company Le Mont St Michel employed seamstresses at home to add the finishing touches to their mass produced clothing lines; they sewed on labels, metallic elements, elastics, zips… In Brest the master tailor’s atelier in the harbour, which made thousands of naval uniforms and hundreds of workwear garments for dockyard employees, worked with dozens of home-based seamstresses; these ouvrières du sac (sack labourers) would collect sacks of cut fabric to take home, and then bring back the sack full of the clothes they’d made from the fabric pieces. Working alongside the travelling seamstresses who took charge of alterations, female pattern tracers, cutters, assemblers, jacket makers, trouser makers and tailors employed at the port were 108 seamstresses out of a workforce of 230 female workers in 1947.

Thus, work industry operators dressed men and women differently, without giving in to gender differences or the power of appearances. Today however, PPE (personal protection equipment), which is in use particularly in the agro-food industry, has established the now regular standardised appearance for workwear.

Translated by : Tilly O’Neill