If any event has become a symbol for interceltism over the last 50 years, it is of course the festival in Lorient. The arrival of this major cultural event in the Breton summer calendar is down to several serendipitous occurrences in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Celtic music wave was on the rise. The festival’s beginnings are first and foremost connected with the renewed popularity of traditional musical instruments and the creation of bagadoù at the end of the 1940s, inspired by the Scottish pipe band tradition. Breton music and pipers’ competitions have existed informally since the 19th century, but the emergence of a structured organisation in the form of the Bodadeg ar sonerion (BAS), a pipers’ association, helped formalise the idea of a regular competition.

The first pipers’ championship took place in Brest in 1953, and very quickly the event became the “International Bagpipe Festival”. Several Scots took part, both on the judges’ panel, and as performers. From the 1960s onwards, Brittany’s bagadoù champions were named annually in Brest as part of an event which quickly became a popular success.

Thousands of people crowded onto the wide avenue known as cours Dajot, near the shipping port, to listen to the sounds of the bombards and bagpipes. The event could well have made its home in Brest, also known as the cité du Ponant, but at the end of the 1960s the Lombardy local government decided to renovate the avenue. The decision was not welcomed by the festival organisers or the BAS and so they decided to change cities. Polig Montjarret, an influential member of the BAS living in Ploemeur on the outskirts of the port city of Lorient in the Morbihan region, suggested they take the festival there. And so Brest lost its bagpipe festival, and Lorient gained its Interceltic Festival.

Bagpipes and Folk Nights

Lorient’s first festival in 1971 may have been a modest affair, but it contained all the components needed to make the festival a success. In particular it offered a pipers’ parade with dancers, a fest-noz and a folk night. The latter was hosted by Alan Stivell, the young Breton singer who’d already won over the Palais des Congrès in Paris, before his hugely successful live concert recording at the Olympia. Gilles Servat and the Goadec Sisters also performed, as did the Dubliners and Cornwall’s Brenda Wootton. The journalist Fañch Gestin wrote of the latter in the 69th edition of ArMen (July 1995): “And finally, an unknown British artist on her first singing tour outside of her native Cornwall…She will be the festival’s mascot, and her name is Brenda Wootton.”

In 1972, the pipers’ festival evolved to become the Interceltic Festival, with Jean-Pierre Pichard as its new director. The organisers quickly realised the importance of opening up the event to the entire Celtic world, something they achieved mainly thanks to the cultural network which had already been developed by the BAS, who had set up exchanges with Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Galicia. That year, the festival also hosted Scottish and Irish pipe bands. The official poster, designed by Micheau-Vernez, shows three pipers from the three different nations, all in costume. Musicians from Cornwall, Wales and the Isle of Man also took part in the festival, while the bagadoù championship final took place for the first time at the Moustoir sports stadium.

From 1973, inspired by Ireland’s Fleadh Cheoil, the singing contest Kan ar Bobl joined forces with the Interceltic Festival, reinforcing the festival’s interceltic outlook. In fact, the winning singers were invited to take part in the Celtavision Song Contest in Killarney. In 1974, The Chieftains performed, as did members of the Breton New Wave, including Gweltaz Ar Fur, bands Bleizi Ruz and Diaouled ar Menez, and singers Djiboudjep. The year 1975 will be remembered for its large delegation of visitors from the Isle of Man, as well as the victory of Bagadoù championship winners Bagad Kemper over Kevrenn Sant-Mark. In 1976, Galicia became a fully-fledged member of this great and contemporary Celtic family. The burgeoning 1970s also included the arrival of the festival’s first international star, Joan Baez, in 1978. At the end of the concert, she danced her first gavotte and would regularly return to Lorient in the years that followed.

Great Compositions

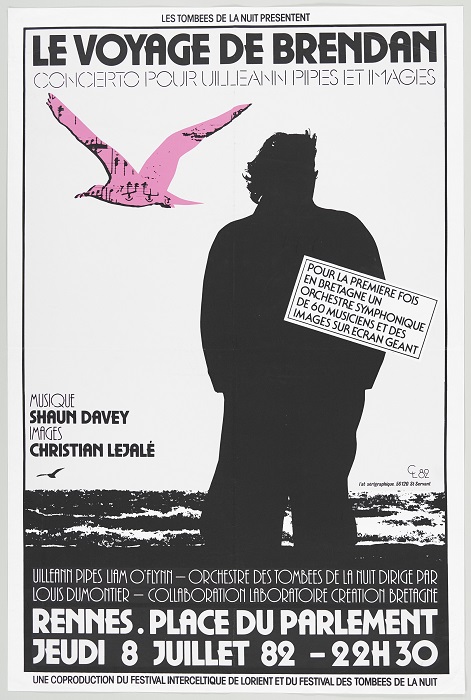

The 1980s are remembered for some tremendous musical compositions based on Celtic themes, bringing together music and instruments from different Celtic nations and sealing the festival’s iconic reputation. A few examples are Alan Stivell’s ‘Celtic Symphony’ (1980), The Chieftain’s ‘Tristan and Isolde’ (1981), ‘Lug’ by Roland Becker (1986), Tri Yann’s ‘Le Vaisseau de pierre’ (1988) and ‘Celtophonies’ by Marc Steckar (1994). But the compositions which have most influenced the history of the festival are those by Irishman Shaun Davey. In his album ‘The Brendan Voyage’ (1982), he blends the Irish bagpipes with a symphonic orchestra, transporting listeners on an unsettling musical journey. Davey returned with his Lorient Celtic suite, ‘The Pilgrim’ in 1983, which included every instrument from every Celtic nation.

In 1985, the festival received its first visit from a minister for Culture; Jack Lang also used the opportunity to announce the authorisation of bilingual signage in Brittany. The same year, Asturias became the eighth Celtic nation to join the festival. With Jean-Pierre Pichard at the helm, the festival also opened its doors to further Celtic diasporas and to more exotic regions. The festival’s first director really understood the appeal of Celtic music, saying: “Right now, we have so much energy to bring in new supporters and create new contacts across the seas. Quebec, Australia, Louisiana and even Japan will no longer be deaf to the musical sounds of Lorient and they will join in our song.”

By the 1990s the festival had matured and was on the hunt to expand its name. It now took place over a ten-day period at the beginning of August, attracting hundreds of thousands of people and had become a professional outfit, employing permanent staff members, as it continued to open its doors to the international community. As Jean-Pierre Pichard put it, “Our strategy was to become more influential outside of France in order to become better known within France. It’s important to note that on top of the festival’s relative insignificance in France, a significant number of Bretons have suffered for having a different culture, and have experienced a painful feeling of being seen as ‘other’” - in his words, the syndrome de Bécassine. “Thanks to the help of foreign journalists, who are regular festival attendees, there are now cultural networks spread across nearly every nation in Europe and the US.”

At the start of the 21st century, the Interceltic Festival reached its cruising speed and became ripe for exportation. The Stade de France requested a series of Celtic Nights during the 2000s. In 2007, Lisardo Lombardía from Asturia took over from Jean-Pierre Pichard and opened up the festival to nations in South America. The festival also began to extend down to the port, even though it meant that some of the bands taking part in these fringe events were lured into Lorient’s many inviting bistrots. There were unmissable events like the interceltic nights at the Moustoir Stadium, with traditional dance troupes performing in shows that lasted two hours. There was also the grand parade and the bagadoù championship final. “A great moment of excitement, even if the event has lost a little of its original spontaneity due to the BAS’s requirements today”, revealed Yann Artur, a piper from the Moulin Vert bagad who has been involved since the 1980s. “The pipers would often head out into the city to play. I miss that, but no doubt the tradition will be reintroduced in time.”

Translated by: Tilly O’Neill