The 1902 ban on preaching in Breton

When in April 1902 the French parliamentary elections took place, tensions between the Catholic Church and the State were already exacerbated. Then on 29th September, Émile Combes, the new President of the Council of Ministers, recirculated a memorandum forbidding the Church in Lower Brittany from preaching in Breton, and urging clergy members hold catechism classes in French only.

![Émile Combes, President of the Council of Ministers of France from June 1902 to January 1905. His memo aimed at banning clergy from preaching in Breton or conducting catechism classes in Breton was debated in parliament on 16th January 1903. “You could well say,” he declared, “that over there [in Brittany], one is Breton before one is French.” There was no risk of the government suffering a minority. MPs approved his bill 339 votes to 185. The mayors of the district of Plabennec replied that they wanted “to be French and speak Breton”. Credit: Basnary, “Portrait of Emile Combes”, digitised collection – Quimper and Léon Diocese, https://bibliotheque.diocese-quimper.fr/items/show/9437. Émile Combes, président du Conseil de juin 1902 à janvier 1905. Sa circulaire visant à interdire la prédication et le catéchisme en breton vient en débat à la Chambre des députés le 16 janvier 1903. « On dirait véritablement, déclare-t-il, que là-bas [en Bretagne] on est Breton avant d’être Français. » Le gouvernement ne risquait pas d’être mis en minorité : les députés approuvent sa politique par 339 voix contre 185. Les maires du canton de Plabennec lui répondent qu’ils veulent « être Français et parler breton ». Crédit : Basnary, “Portrait d'Emile Combes,” Collections numérisées – Diocèse de Quimper et Léon, https://bibliotheque.diocese-quimper.fr/items/show/9437.](/becedia/sites/default/files/medias/dossiers-thematiques/breton%20d%C3%A9but%2020e/1-Portrait-Emile-Combes.jpg)

It’s important to note that at the time, parish priests were paid by the State, like civil servants. Over a three-year period, 127 clergymen (including 87 in Finistère, who represented 14% of people paid by the State in that department) had their pay suspended for “unwarranted use of the Breton language”.

There was an outcry at the decision. However the head of government, its departments, and even the diocese of Quimper and Léon weren’t really aware of the lie of the land. Quimper’s Bishop Dubillard therefore asked his priests and 'rectors' to inform him as quickly as possible on which language was most used for delivering catechism classes. Meanwhile, Émile Combes urged the Finistère state representative, Henri Collignon, to carry out his own survey. Never had such a widely carried out survey on language use ever been organised in Lower Brittany in terms of both qualitative and quantitative, not to mention contradictory, data.

Breton was spoken by adults, but not everywhere

In response to the Bishop’s survey, members of the clergy examined the state of the spoken language at the start of the 20th century by considering the adults to whom they addressed their sermons. In rural communities, sermons were exclusively delivered in Breton and “never in French”. For the rector of Plonéis and many others, it was “impossible to make oneself understood from the pulpit if one didn’t give sermons in Breton.” The presence of the Breton language was less evident in towns. In Saint-Pol-de-Léon and Audierne, priests preached in both languages at Sunday mass. For every Sunday mass in Breton there were two in French. And in cities like Quimper, Brest or Concarneau, masses were mostly held in French.

This led to further questions: Did Breton-speakers therefore not know how to speak French? And did those who could speak French not understand Breton? The rectors took an entirely pragmatic view on this. For them, the primary determining factor was which language was used by the majority. In a rural parish, if they decided that “the whole congregation” understood Breton bar a few individuals, then they held mass in Breton. “Do you think priests wish to preach in a language their listeners don’t understand?” asked the priest at Trédarzec in Trégor.

The social class of those attending a mass also influenced the decision. In Quimper and Brest the masses held in the early hours and mostly attended by labourers and servants who’d come in from the country were held in Breton. In Saint-Pierre-Quilbignon near Brest, mass was still held in Breton at the request of the dockyard workers. The introduction of French was also linked to the development of tourism and seasonal work. The rector at Plougasnou spoke in French “in the summer when there were bathers”, as did the rector at Penmarc’h during the sardine fishing season and the holidays.

What the state school teachers said

Émile Combes was puzzled when his Finistère colleague informed him that in 1902, Breton was the only language spoken by men over the age of 40 and he asked him for more precise information on the 123 villages considered to be “resistant” to the use of French in church. Information collected by the gendarmes, who travelled on foot or by horse to the places concerned, was scanty. They were not well-received by the inhabitants and their presence “produced a high level of excitement”, so the deputy state representative at Morlaix decided to ask the teachers instead.

Their statements were contradictory. Whilst confirming that it was indeed a question of age, several said that “the majority of the population understands Breton more easily than French”, whilst others said that “those living in the community can speak or understand French”, which of course did not mean that the inhabitants didn’t speak Breton. One teacher added that “On leaving school or returning from the army, children and young men quickly forget the little [French] they may have learnt.” Another remarked that there “are also people here who don’t understand a word of Breton”.

A changing linguistic landscape

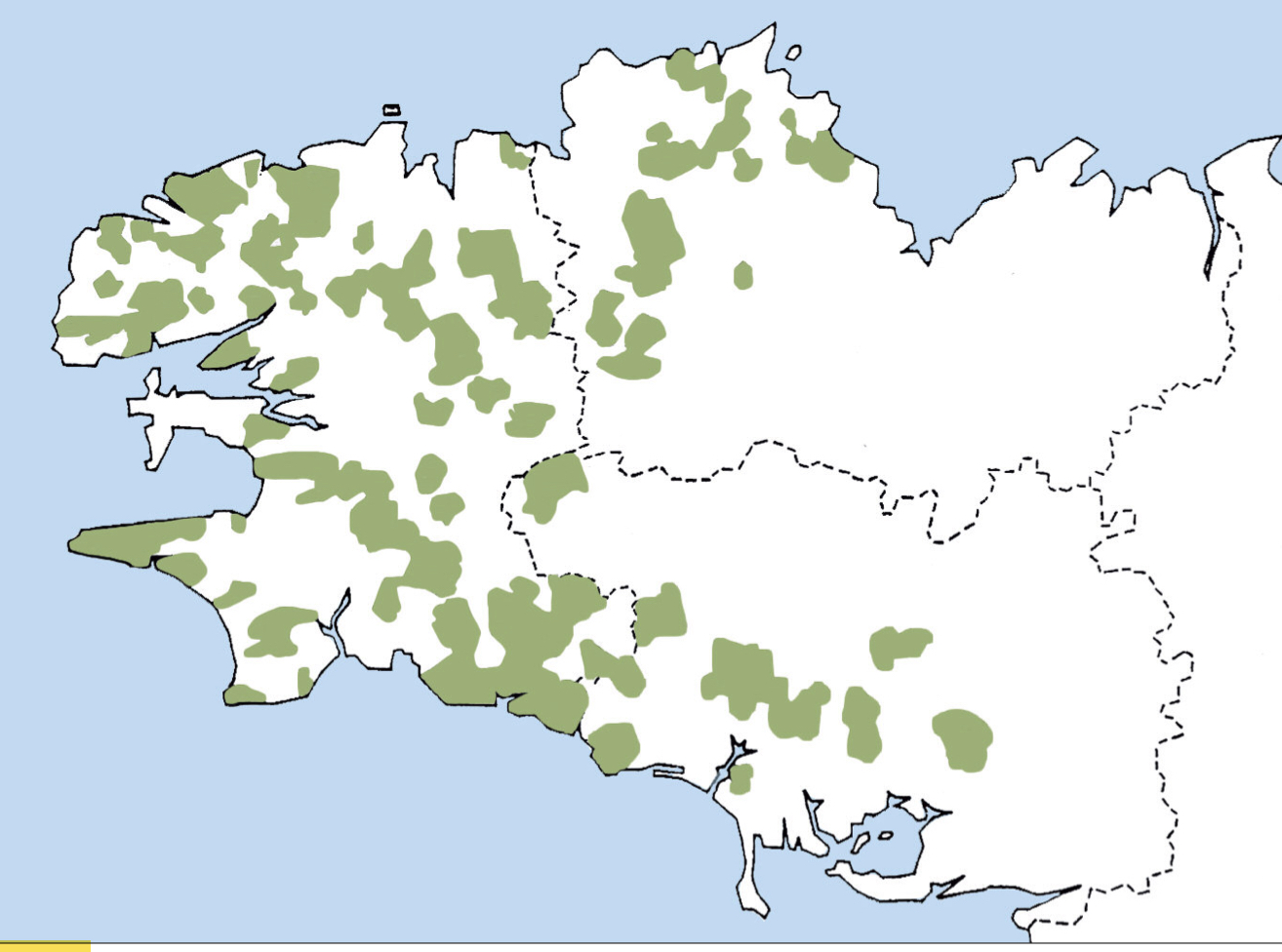

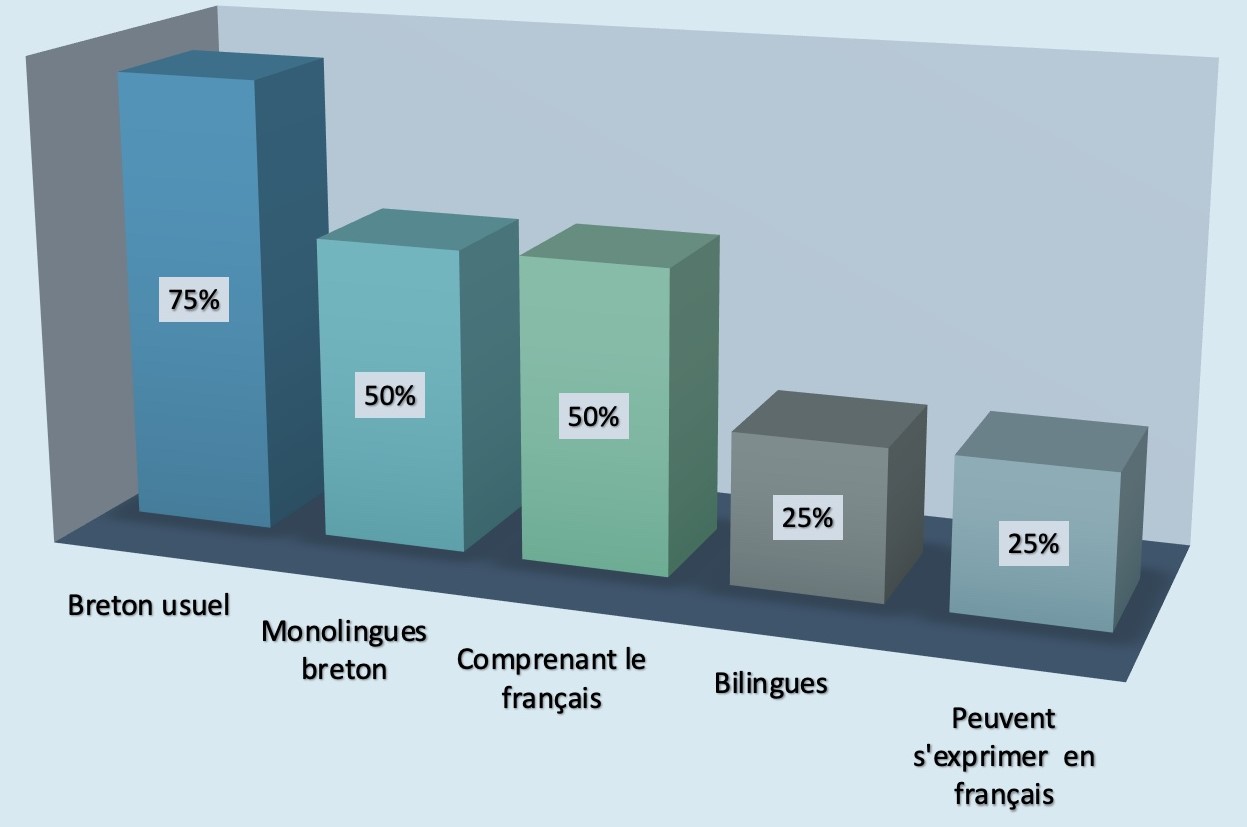

If we apply both the clergy’s observations as well as those of the Finistère civil authorities at the start of the 19th century to all of France’s Breton-speaking areas, the linguistic landscape of Lower Brittany at the time can be broken down into the following categories, although these are not cumulative:

- Half the population was monolingual Breton-speaking, a sign of change since the 19th century. The percentage of children receiving catechism lessons in French at the beginning of the 20th century was another sign of change.

- Three quarters understood Breton and usually only spoke in that language.

- A quarter were bilingual.

- Half the population were capable of understanding French.

- A quarter were capable of speaking in French, exclusively if they didn’t speak Breton, and occasionally if they did.

Language use also varied depending on demographics and geography. The younger generations understood more French than the older ones. Use of Breton was generally systematic in rural areas: the authorities themselves recognised this. Inversely, French was dominant in towns and cities, even though many inhabitants also spoke Breton. French was starting to make a breakthrough in rural areas, a change which had sparked controversy.

Translated by Tilly O'Neill

![Class photo from the hamlet of Saint-Adrien, Plougastel-Doualas,1905. According to the parish priest, 230 out of 246 children were “incapable of learning their catechism in anything but Breton […] because 98 out of 100 families only speak Breton, whether or not they also understand French.” Photo credit: Trégarvan’s Musée de l'école rurale.](https://bcd.bzh/becedia/sites/default/files/dossiers-thematiques/3-ecole-hameau_saint-adrien-plougastel-ok.jpg)