There is some confusion about the nature of Gallo. Should it be referred to as a form of ‘patois’, as a dialect or as a language? The sociolinguistic definitions of these terms remind us that they reveal different opinions on the same subject. ‘Patois’, often considered a disparaging term historically, is still used by a large number of speakers. Romance language dialectology in particular considers Gallo a dialect, implicitly categorising it as subordinate to the French language. This view suggests Gallo is a ‘basilect’, meaning the most different version of a more prestigious language, known as an ‘acrolect’, in this case Parisian French. This terminology, which came about as a way to describe French Creole when it is used alongside French, seems very useful for describing Oïl languages. But a basilect can become a separate language through social and political motivations, and starting in the 1970s, campaigners demanded Gallo be recognised as a separate language. This was a revolutionary and symbolic act aimed at restoring the image of a much-maligned form of expression. In the same vein, today the Institut du Galo promotes the name langue gallèse, or Gallese language. The semantic slide that has resulted from these activist campaigns now categorises Gallo as a language in a state of ‘individuating-emergence’, according to sociolinguist Philippe Blanchet.

The fact remains that Gallo’s precise connections with French arouse curiosity. French is considered the point of reference as the more dominant of the two and it has affected Gallo’s evolution, especially since the 19th century, when the number of local expressions started to decrease with every new Gallo-speaking generation living within a diglossic context. Furthermore, code switching, or language alternation, has become a very real phenomenon amongst Gallo speakers, whether consciously or unconsciously (for example, as a strategy to adapt to the person they are speaking to). Thus, according to Vincent Morel, for the majority of speakers who switch between French and Gallo, might be more about adjusting to one's partner in conversation than about crossing a boundary. This is also what we find in the case of Creole languages, whose status as a separate language is now well established. Finally, its exclusion from public life after decades of stigmatisation has meant Gallo has often sought refuge within tightknit circles in which is is already recognised and with which it already has connections.

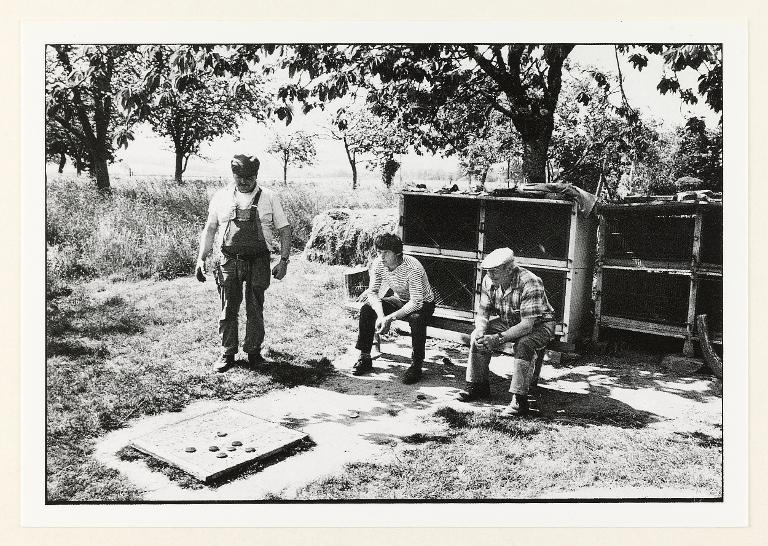

The spontaneous use of Gallo is often reserved for local social interactions - between parents, neighbours, or close family/friends from the same social circle. In these cases, there is a readjustment in favour of Gallo. It’s hard to imagine these palet players only speaking in the approved French of the Académie française.

In response to this evolution, the campaigners support a contemporary use of Gallo aimed at recovering the lexical and grammatical wealth which is continually being lost, as well as recovering social spaces. This focus on the language itself is helping to transform it. It necessarily means mixing different Gallo variations, as shown by the now generalised usage of localised terms. A good example is the word ôtè (house) which is well-recognised amongst neo-Gallo speakers. Its use was limited to certain parts of the Côtes-d’Armor in the middle of the 20th century, despite the fact that certain place names further east suggest it was more widespread in previous centuries (L’Hôtel Hamon in Bédée and Les Autieux Renault in Breteil, Ille-et-Vilaine).

One big problem with updating a language in this way is that it can lead to an extension of the meaning of a localised term (for example, isouéte, 'a group of people who mutually assist each other for farming tasks', is now used to mean ‘association’). It can also result in invented words, some of which have become common parlance (for example, motier for ‘dictionary’), and some of which have not caught on so much (vaerouilére for ‘multimedia library’). Local forms of words that least resemble the French equivalent tend to be preferred (terouer rather than trouver).

Ultimately, as is the case for most ‘regional languages’ in France, there is still continuous debate surrounding the correct degree of terminological innovation to apply (like Breton), and there are many who seek standardisation (like Occitan).

Translation: Tilly O'Neill