The first agricultural penal colonies for young convicts appeared in the mid-19th century. The French Revolution of 1848 had led to a feeling of fear amongst leaders within the elite classes, who wished to gain greater control over the working classes. The aim of these agricultural colonies was therefore to re-educate boys born into poverty by turning them into farm apprentices. As well as the project’s more repressive objectives, it was also seen as a way to combat the mass rural exodus that was then taking place. The boys were given the job of clearing parcels of land that were otherwise uncultivable, with the aim of getting new populations to settle there. A law passed on 5th August 1850 inspired by the recent and already well-known agricultural penal colony in Mettray near Tours, offered a legal framework for the many private initiatives being established in France at the time.

An institution of its time

The advent of the Third Republic at the start of the 1870s was an opportunity to re-evaluate the French prison model. A proliferation of scandals surrounding the mistreatment of inmates had shocked public opinion. The effectiveness of the agricultural training, which was mainly given to boys from the city, who would often simply return home once they were released, was also widely criticized. The new Republic took it upon itself to update crime and punishment laws. The 1872 parliamentary commission therefore recommended the opening of state-run penal colonies which would offer a variety of professional training programs to those in their care. And thus, Belle-Île-en-Mer’s penal colony was first established.

An atypical prison model

The institution opened in 1880 and was one of a kind. Run by the state, it was the first public correctional facility to be opened in Brittany. In just a few decades it replaced the private establishments in Saint-Ilan (22) and Langonnet (56), which closed their doors in 1888 and 1902 respectively.

From then on, Belle-Île-sur-Mer’s penitentiary became Western France’s main correctional facility. As a member of the very exclusive group of French prisons established on islands, its location offered the public authorities a whole host of guarantees. The natural barrier formed by the sea stopped any escape attempts, as well as isolating wards from their friends and families.

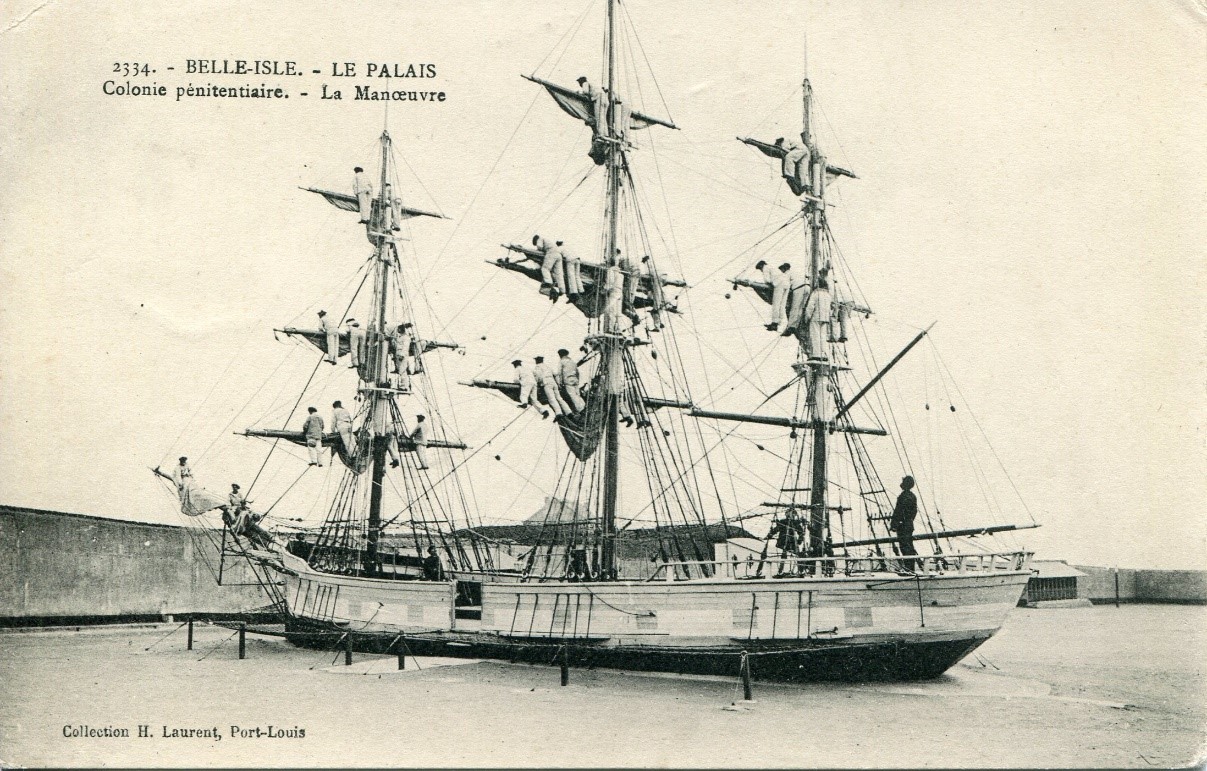

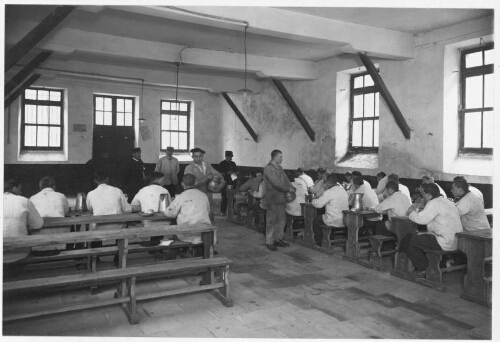

The archipelago’s correctional unit was spread over three sites, all located in Palais. Haute-Boulogne Prison, built in 1848 and which had up until that point only held adult prisoners, was the institution’s nerve centre. It housed the workshops, most of the dormitories, offices for administrative staff, the refectory and the infirmary. It also contained the naval unit, which offered full training for wards (navigation, rope, sail and net making), as well as the industrial unit which taught the basics for various trades (shoemaker, tailor, carpenter, stonemason, blacksmith, etc).

The cellars of Château-Fouquet, close to Haute-Boulogne, were used as cells for the establishment. Dark and frightening, they mainly held badly behaved inmates waiting to be transferred to harsher institutions. Further inland, the farm at Bruté hosted the agricultural school, which also offered training in many other professions (gardening, animal care, forestry…).

Amongst this exceptionally wide range of occupational training programs, the naval unit was the pride of the Ministry of the Interior. The opening of the Belle-Île-en-Mer penitentiary colony was indeed the result of a long-term project to create a correctional unit for apprentice sailors in France. After several abandoned attempts, the French prison service felt they had found the right formula and that they could finally compete with Britain’s floating prisons, which were the envy of every international prison congress. From then on, the institution became the standard for correctional education in France. But the glowing reports of the naval training unit were hiding a much darker reality: as in every prison, the young inmates suffered physical abuse on a daily basis.

Ward mistreatment

The French prison service opted for military-level discipline in order to set its wards back on the right track. A bugler would wake them every morning, all movement was done in military steps, and blank weapon manoeuvres took place almost daily. The establishment was organized as a ‘school battalion’, the aim of which was to send wards directly from the colony to the barracks. France was preparing its revenge for its defeat by Prussia in 1870 by transforming boys who were vagabonds, beggars or petty thieves into obedient soldiers. The colony on Belle-Île-en-Mer, which looked much like a military prison, was therefore intended to be considered as a small military barracks.

Many inmates were left traumatised by these conditions. Wards were first and foremost victims of repeated physical violence. Despite regulations prohibiting all forms of brutality, they were the privilege of the institution’s guards, who were for the most part ex-military. But they were also inflicted by the inmates themselves. Physical appearances varied greatly, as did age, from child through to young adult. The inherent psychological pressures associated with being imprisoned only added to this distressing context. Wards experienced the geographical distance and separation from their families in many different ways, and the emotional shock was compounded by mistreatment, of which the boys were either witnesses or victims. Whether physical or psychological, the scars of their time spent in detention stayed with them for the rest of their lives.

The failure of a brutally violent programme

The Third Republic’s prison system claimed to straighten out street urchins in its prison colonies, and offer the keys to societal reintegration. But this official line went against the daily realities of the Belle-Île establishment. The correctional program was a resounding failure, as were many other disciplinary institutions (barracks, labour camps, prisons…), and in 1927, the penal colony became a Maison d’éducation surveillée (house of supervised education).

In reality, the system and behaviours remained roughly the same and the escape of 56 minors on August 27th 1934 highlighted the intolerable conditions in which the boys were living. It wasn’t until a ruling in 1945, and the creation of Institutions Publiques d’Éducation Surveillée (Public Institutions for Supervised Education) that the first trained educators arrived in Palais. The institution closed its doors forever in 1977.

Translation: Tilly O'Neill