An Improvised Resistance

Following the surrender of Napoleon III’s army in Sedan on September 4th 1870, the Republic was declared. Paris was besieged by the Prussians which led to an attempt by the government of national defence to take action. Gambetta, Home Secretary and Minister of War was delegated to Tours and there he ordered “a full-on resistance.” He planned on restraining the enemy by raising an army of volunteers. This army was placed under the direct rule of Freycinet, an engineer from the Ecole des Mines who was named representative of the war and not of the general military staff.

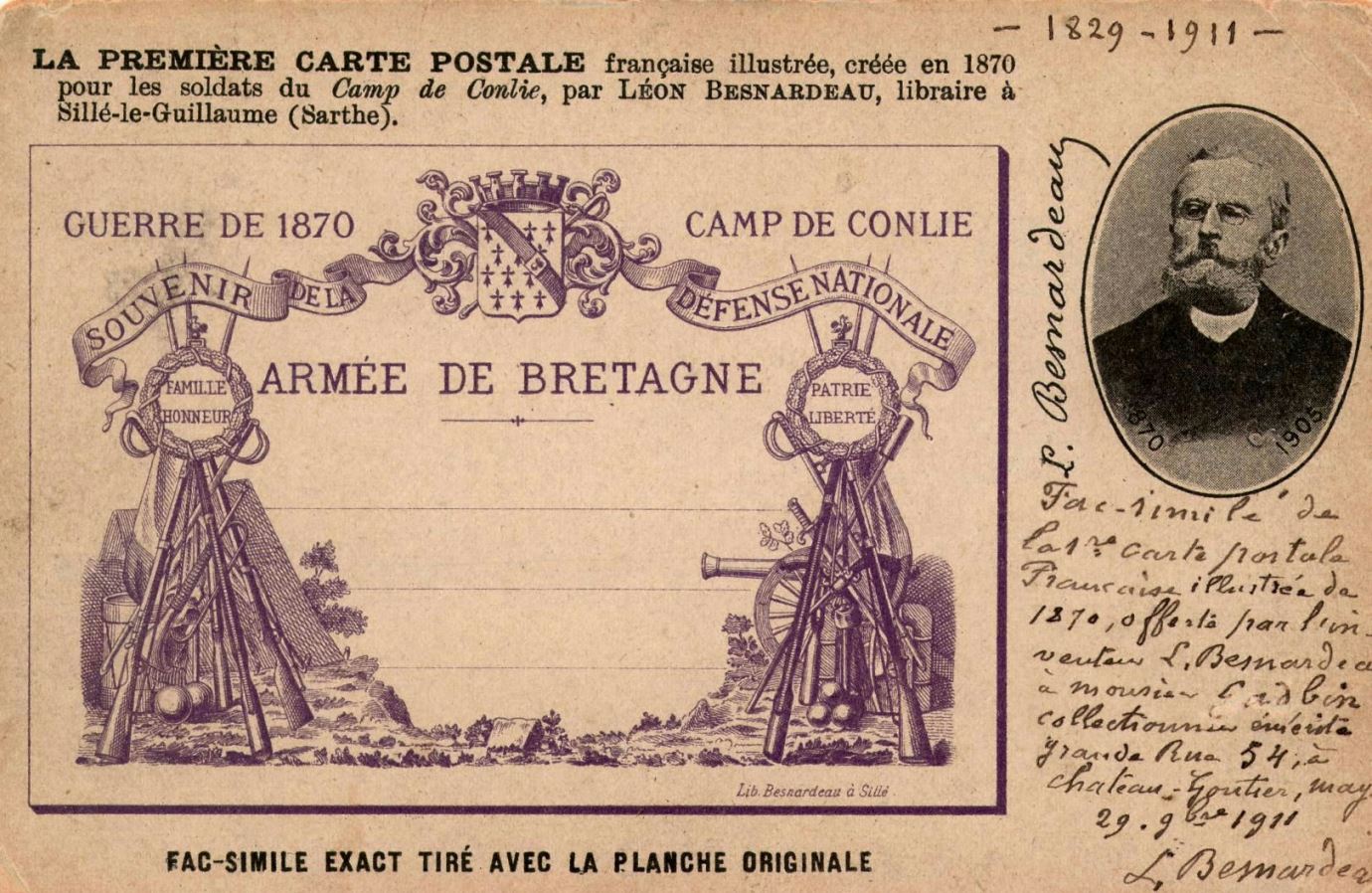

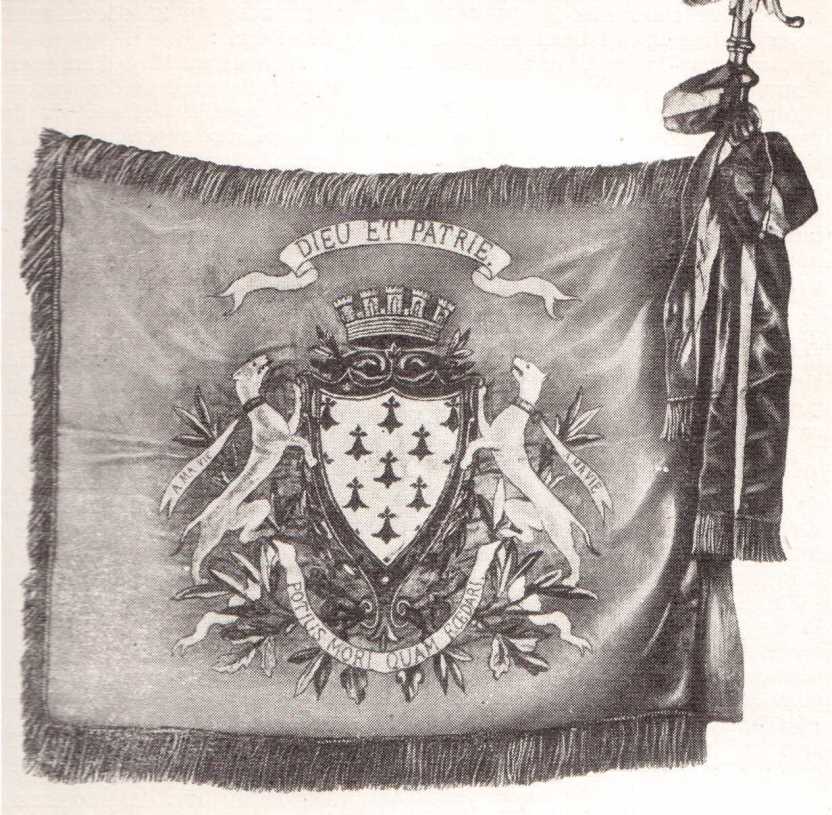

The decision to create eleven entrenched camps to assemble, arm, equip and train the volunteers did not resonate with many people. The Bretons, at the instigation of Keratry, who believed in the idea of a mass sign-up, were the first to respond to the call of duty.

Kerfank

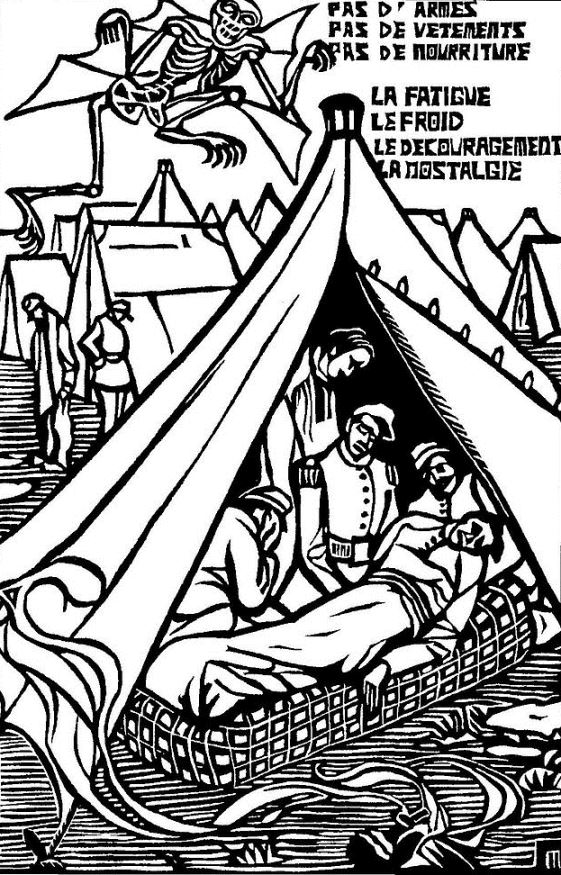

On October 22nd, Émile of Keratry, obtained complete authorisation to form the “Army of Brittany” and to create a camp for them. He chose to gather his men in Conlie, a strategic position to the North-West of Le Mans. A freshly ploughed plateau was hastily put into order to receive the first volunteers who arrived on November 6th. That year, the autumn showers were particularly heavy and rapidly transformed the site into a mire into which the men sank up to their knees. The site quickly took on the name Kerfank, “the town of mud.” The total disorganisation of the administration worsened the living conditions and the men lived without any kind of comfort or support in tents, a situation comparable to the colonial wars. It wasn’t long before illnesses (including smallpox) started to develop.

An Army without Weapons

The disorganisation also affected the military equipment. At the end of the American Civil War in 1869, the United States sold off their weapons to the French. But the government decided that the obsolete, muzzle-loading and faulty firearms would suffice for untrained soldiers. Gambetta even went as far as to deliberately delay, even prohibit the distribution of the firearms that Keraty demanded. There were several reasons for this. First of all, there existed a political mistrust between two figures, Keratry and Gambetta, secondly, the regular army was hostile towards this auxiliary army under the control of politicians and finally, there was a mistrust of the Bretons. The not so distant memory of Chouannerie (a civil war between republicans and royalists which took place in the West of France) was still fresh in people’s minds: “I beseech you to forget you are Breton so that you may only remember your French qualities” Freycinet telegraphed to Keratry.

“We’re Dying Silently and Enough is Enough”

Furious at being placed under the command of Benjamin Jaurès, a sea Captain promoted to General, Keratry resigned on November 27th. “If I’d known that I would not have weapons, I would not have raised an army,” he proclaimed with regret at that time. Marivault, appointed on December 7th, made an overwhelmingly negative report: “43 000 men, of which barely half of them are armed with 11 different models of guns.” In a telegram on the 17th, he announced the resignation of Doctor Cuche who was unable to treat the sick lying in water and he concluded “We’re dying silently, enough is enough.” He proposed to withdraw some of the soldiers towards Rennes, since they had nothing to offer them, neither training nor weapons. Gambetta preferred to keep them in Conlie. Some soldiers cried out “d’ar gêr” (home) which Marivault, not understanding Breton took for “à la guerre!” (To war!) He prepared the evacuation against Gambetta’s orders.

Called to the Battle Front

On December 11th, the General Gougeard from Lorient, took charge of the troops that were entrusted to him. Without waiting for an order, he sent more than 20 000 men home and created a division with the 140 men who remained in Conlie (principally from Ille-et Vilaine). They joined the General Chanzy’s Loire army. The Bretons’ attitude was exemplary despite the lack of preparation and equipment. However, Chanzy blamed his defeat in Le Mans, on January 11th and 12th, on the retreat of the Bretons on the Tuilerie site.

“Deplorable Waste”

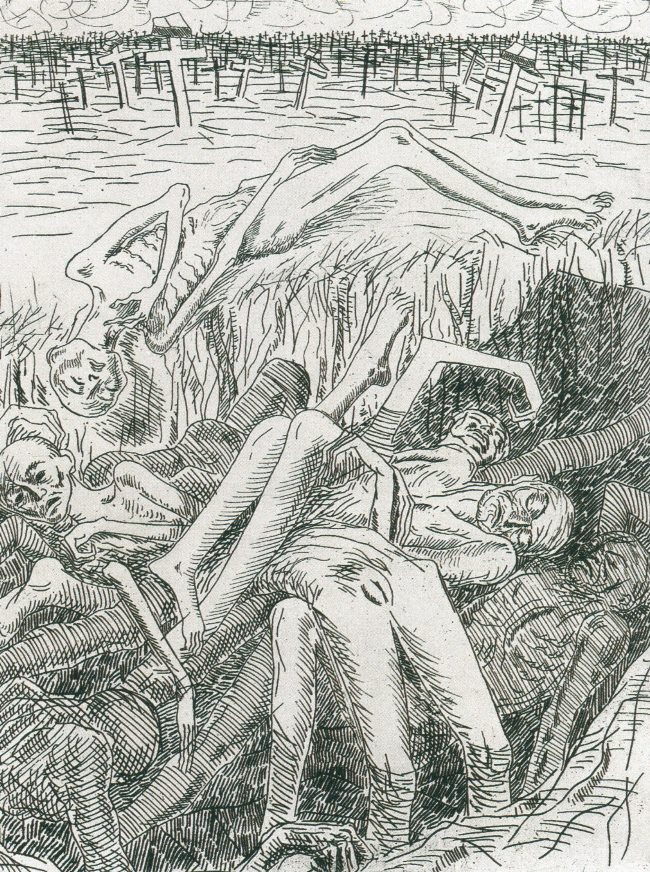

The archives report 143 deaths amongst the 60 000 men who went to the Conlie camp and more or less the same amount in Sillé-le-Guillaume where the soldiers were sent for medical attention. It was therefore far from being genocide. However, the pitiable state of the soldiers upon their return to Rennes provoked indignation and a parliamentary inquiry commission wrote a report on the camp the following year.

The largest part of the blame fell upon Napoleon III, who engaged France in a war despite admitting himself that the country was unprepared.

Gambetta and Freycinet were more haunted by the fear of a repeat of Chouannerie than concerned about saving France. “Deplorable waste” Gambetta wrote in December 1870 after having seen the reports on the camp. “You are a charlatan!” accused Jules Grévy, one of his colleagues in the government.

Keratry, more inconstant than competent, revealed himself to be ambitious but indecisive and unrealistic by handing in his resignation and then taking it back a number of times.

The inability to make coherent decisions was primarily due to the incompetence of a provisional government that drowned-like the Bretons had drowned in mud in Conlie- in problems that overwhelmed it, when the leaders allowed themselves to be led by their prejudices, passions and ambitions.

This is what the inquiry commission ordered by the Chamber on June 13th 1871 highlighted, but that was all!

“We are at the origin of a major moment, a misunderstanding between Brittany and France which marks the beginning of the moment where the Bretons would be represented as utterly backwards country bumpkins, this was the first expression of scorn that would lead a certain number of Bretons to revolt morally and physically. Camille Le Mercier d’Erm, who was one of the first to denounce Gambetta’s policies through L’étrange aventure de l’armée de la Bretagne (The Strange Adventure of the Army of Brittany) was a very young man in 1911 whilst he partook in the founding of the first Breton nationalist party” Michel Denis reminded us over the France Culture’s airwaves in the show, La Fabrique de l’Histoire (The making of History), February 16th, 2004.