When the Allies launched Operation Overlord on the Normandy coast on 6th June 1944, the tranquil village of Gouesnou just north of Brest had been occupied by Wehrmacht troops since 20th June 1940. No notable events had occurred during its occupation, but because of its proximity to Brest, the village had fallen victim to stray bombs aimed at the city on more than one occasion. By 15th January 1942, no fewer than 179 bombs had fallen on the area. Except in Brest itself, there was little resistance to the Occupation, although small Resistance units had gradually begun to form in the region. In Gouesnou, a dozen people had formed a group, led by Philippe Prédour, in the spring of 1943. He was a man of 32, working on his parents’ farm who had up until that point been a Vichy army recruit. The group considered itself part of the Défense de la France, and in the summer of 1944, they would join the FFI. Between 1943 and 1944, their actions were fairly tame; hiding small numbers of weapons for the Brest Resistance forces for instance.

Between the 6th June landings and mid-July 1944, the Allies progress was much slower than anticipated, as troops tried to make their way through the dense Norman undergrowth. At the end of July, the Americans finally broke through the front of their sector, with thanks in particular to the Third Army’s leader, General George Patton. Once they reached Brittany on 1st August, the Allies quickly made their way towards Brest in order to make use of its deep water port, which was logistically fundamental to their mission. But the German army had turned the city into a powerfully-defended festung (fortress). The port, which had been transformed into a submarine base – for their famous U-boats – was of huge strategic value. In addition, since the American troops were advancing, German troops deployed in Brittany were ordered back to Brest, thereby increasing its defence numbers.

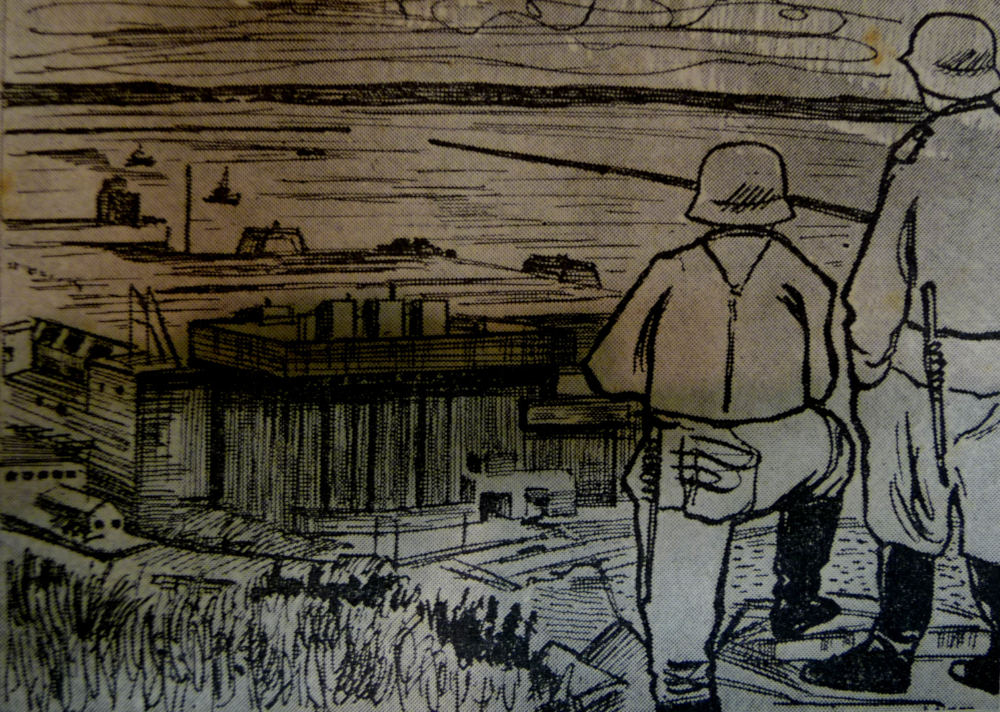

Leaving the Rennes region on 4th August, the 6th Armoured Division made swift progress. In three days, it had Brest in its sights. On the evening of 6th August, the Americans had reached Plabennec, less than 2 miles north of Gouesnou. But the situation was precarious. They were fighting off the German 343rd Infantry Division from the south, along the Milizac/Gouesnou/Guipavas line, but also the 266th Infantry Division from the north, in the Lesneven area. On 7th August at midday, the German general staff based in Brest declared a state of siege. The Americans, who had not managed to attack Brest, received support from the FFI, who acted as scouts and guides and for the American troops.

Germans under siege

In Gouesnou, resisters were informed that German soldiers had set up an observation post in the church bell tower, from which they were coordinating attacks. Worried they would be too exposed to German artillery, the Americans refused to move in with their tanks. A light infantry attack was therefore needed. Philippe Prédour and the Americans called in the Special Air Service (SAS), France Libre parachutists trained by the British in close combat and commando tactics. They were dropped in small groups of between 8 and 10 men in the Finistère region at the beginning of August, as part of Operation Derry. Their objectives were to secure the Morlaix and Plougastel bridges, locate the German army’s positions and to help the Resistance movement. In the Lesnevel area, a group of 8 SAS men, Stick 4, were dropped during the night of 4th/5th August, with Sublieutenant Maurice Gourkow in command. The group’s mission was to make it to Brest, mapping the enemy’s position a they went.

These were the SAS members who arrived as FFI reinforcements to attack the bell tower. The attack started around 2pm and lasted just 20 minutes. The Germans clung resolutely to the church and managed to call in back up from a base in the hamlet of Roc’h Glaz, just over 2 miles away, in the commune of Lambézellec. It arrived swiftly. Severely outnumbered by German soldiers, the SAS and FFI ordered a northwesterly retreat, at which point two SAS soldiers were killed. The group then headed towards the Gouesnou/Saint Renan road where it attacked a German convoy, freeing a group of North-African prisoners (their precise number and origins are as yet unknown), who seized the Germans' abandoned weapons and fled.

The Penguérec Attack

The Germans decided to react to these ‘terrorist’ attacks by taking hostages. For them, this was the only possible form of response. In fact, since the Sperrle and Keitel decrees of 12th February and 4th March 1944, the German military had no choice but to respond in the harshest way possible to partisan attacks against soldiers or German bases. They would open fire, isolate the area concerned, arrest all civilians in the area and burn down houses. They did not need to wait for authorisation from their superiors for this. Rather, if they did not carry out these orders, the officer in charge would be severely punished. Sperrle’s decree even stated that the measures taken, however excessive, would not be subject to sanctions.

Towards 4pm, a truck from the Rac’h Glaz base drew up in front of the Phélep family and Simon family farms in the hamlet of Penguérec, southwest of Gouesnou centre. The soldiers were part of the 805th Marine-Flak-Abteilung of the Kriegsmarine. These were marine artillerymen whose job was to shoot down allied planes on their way to bomb the naval base. As soon as they arrived, they sprayed the Simon farm with bullets and set fire to the haystacks. The Simon family sought shelter at the Phélep farm on the other side of the yard. The two families grouped together in the kitchen and watched the Germans through the window, at which point Jean Phélep went out into the yard, tea-towel in hand in lieu of a white flag, to parley with the German soldiers. But there was little point. The Germans threw grenades through the window. Yvette Phélep, 12, was hit in the leg by the explosion but managed to escape out a backdoor. Very quickly, the Phélep’s farm was also set alight. Marie-Louise Phélep, Jean’s wife, and her daughter Francine tried to free the animals from the flames, but they were also shot. The son, Pierrre Phélep, 21, tried to escape through the fields, but he too was killed, as was Marie-Jeanne Kerboul, 20. Jean Phélep, who managed to escape at first, was caught up a hundred metres from his farm and shot in a ditch. The Germans also fired on the Luslac family farm which was on the other side of the hill. Jacques Luslac was severely injured. At the same moment, his daughter Marie-Jeanne and her son René were arriving in a charabanc. Both were immediately shot.

42 victims

At roughly the same time, the Germans began rounding people up in the village itself. These were mainly Gouesnou locals, but also people who had been evacuated from Brest that morning. They also rounded up people from the different hamlets around Gouesnou. After several hours spent lined up against the wall of the church in the blazing sun, the men were separated from the women and children and taken to Penguérec, where they were tied together in groups of two or three and shot. Their bodies were then piled onto a manure heap which the Germans set fire to. Nearly a week later, around 14th August, on German orders, three members of the Gouesnou community were made to bury the bodies in shallow graves. They were later interred in a communal grave in Gouesnou cemetery in January 1945. Among the massacre’s 42 victims, nine have not been identified. It is possible they were members of a Resistance unit associated with Pierre Phélep, one of the young men from Penguérec, but there is no source to confirm this hypothesis.

Although no German archives can precisely confirm the names of those responsible for the massacre, it was very likely the soldiers of the 805th Marine-Flak-Abteilung. They were the German unit closest to Gouesnou, and some of the soldiers were recognised by locals. After the war, there was no trial to condemn those responsible for the crime. It was time to turn the page, rebuild France and gradually reforge ties with Germany. The money allocated to finding ‘petty’ German war criminals was almost non-existent. In addition, the Bordeaux trial fiasco of 1953 for those responsible for the slaughter of 642 people in Oradour-sur-Glane only served to discourage others from seeking justice.

Translation: Tilly O’Neill