From 1562 onwards, France was ravaged by the Wars of Religion between the Catholics and the Protestants. The Protestant presence was limited in Brittany and thus on the whole, the province remained isolated from the troubles. In 1584 however, tensions exacerbated when Henry of Navarre, the head of the Protestant party, became the legitimate heir to the French throne, to the great displeasure of the Catholics. Following its governor, the Duke of Mercoeur, Brittany gradually joined the Catholic League (a major participant in the Wars of religion which wanted to eradicate Protestants.)

The Attack on the Castle

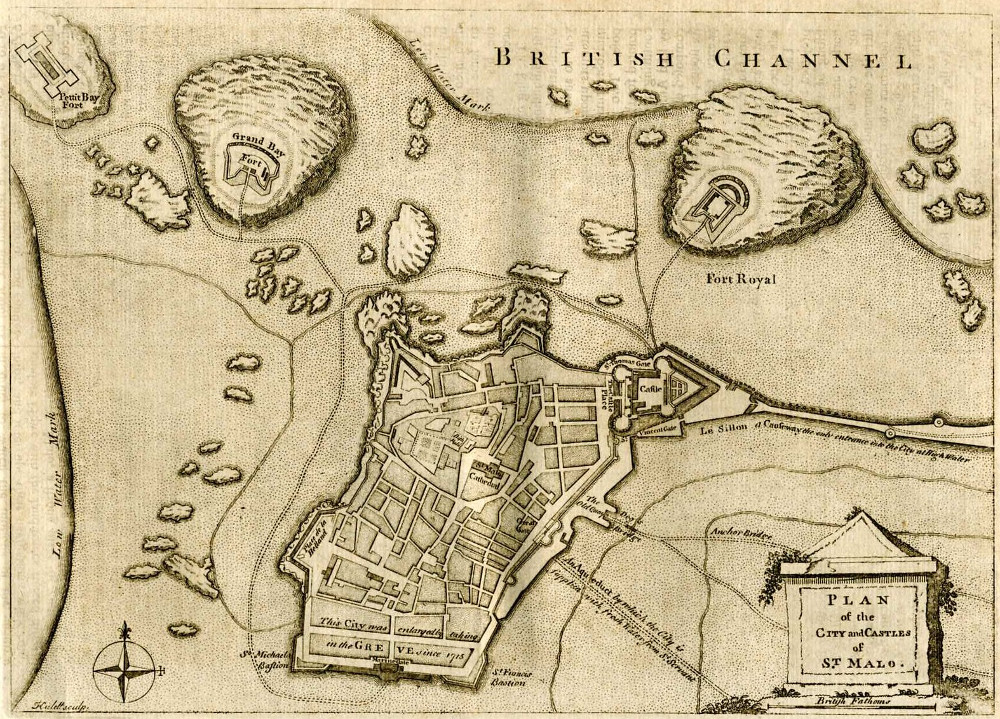

Faced with rising tensions, the inhabitants of Saint-Malo undertook the task of defending their economic interests which were under threat from the civil war. It was a fortified and episcopal town, home to a large diocese extending towards Ploërmel and was equally a sea-trading town. The bourgeoisie soon became a social force. In 1585, the inhabitants elected a Council of twelve conservatives, the core of the future republic of Saint-Malo. When Henry III was assassinated in 1589, the inhabitants of Saint-Malo refused to acknowledge the new King, Henry IV, and found themselves at odds with the royalist governor of Saint-Malo. When Henry IV was on his way to Saint-Malo, the governor of Fontaines announced his intention to open the city gates for him. The rupture was complete. The principle public figures of the town fabricated a plan to seize the castle where the governor resided. The castle protected the city of Saint-Malo by regulating the access into the city but it also served as a means of surveying and controlling it. The attack, during which the governor perished, was carried out during the night of the 11th to the 12th March 1590. It was the beginning of the republic of Saint-Malo.

From then on, the Council took all the necessary measures to govern itself independently, up until the accession of a Catholic king to the throne. The Council elected the magistrate Jean Picot of the Gicquelay as the “leader and president of the Council in charge of the government of the town and castle” of Saint-Malo. Gradually, Saint-Malo established complete sovereignty with the governing Council defining its very own policies in sectors as diverse as defence, foreign relations, finance, police, justice and trade.

![Map of Saint-Malo harbour and of a stretch of the river Dinan [détail] - Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, CPL GE SH 18 PF 44 DIV 3 P 3 D RES Map of Saint-Malo harbour and of a stretch of the river Dinan [détail] - Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, CPL GE SH 18 PF 44 DIV 3 P 3 D RES](/becedia/sites/default/files/medias/dossiers-thematiques/la-republique-de-saint-malo/carte-rade.jpg)

Complete Independence

As early on as the end of March 1590, even a veritable autonomous foreign policy had been devised. Trade with the kings’ followers was prohibited. Conversely, the cities of Morlaix, Lannion, Saint-Brieuc and Roscoff were visited by a deputy from Saint-Malo, tasked with informing them of the political change and assuring them that relations would continue as usual. On an international level however, Saint-Malo strived to maintain good trading relations with England, the Dutch Republic and the Hanseatic League, informing them of the political change in Saint-Malo, but reassuring them that they wished to maintain free trade despite their religious differences.

Saint-Malo did not acknowledge Henry IV, neither did it acknowledge the authority of the Duke of Mercoeur and would never allow him into the city. In order to protect themselves from all attacks from the Duke of Mercoeur, the pragmatic inhabitants of Saint-Malo appointed a deputy to ask for the aid of the Duke of Mayenne, head of the League of France and of the King of Spain. They essentially remained independent by playing the competitive and ambitious powers of the era against each other.

Even though Saint-Malo gave priority to diplomacy and pragmatism, it also established a powerful military force which possessed one of the best fleets of the era. Saint-Malo therefore succeeded in protecting not only the security of the inhabitants but also the commercial interests of the powerful trading families who dominated the Council. Throughout the period, trade flourished which contrasted to the crisis that was widespread throughout the rest of Brittany. Saint-Malo became a real depot where ammunition, weapons, canvases, cheap jewellery and even oranges were stored! The supplies, which were so cruelly lacking in the rest of Brittany, conversely accumulated in the Republic.

The Edict of Reduction

On the 25th July 1593, Henry IV converted to Catholicism. Having sworn to govern itself autonomously during the interregnum of waiting for “God to give a Catholic king to France,” the autonomous Council lost its primary reason of existence. On April 1st1594, the town assembly appointed a delegation to discuss with the king, with the aim to reintegrating completely with the rest of France. The inhabitants of Saint-Malo and the king negotiated almost as equals. After months of negotiations, the king finally granted the majority of their demands, which culminated with the edict of Reduction, which he signed on the 4th October 1594. It was the end of the Republic of Saint-Malo. Throughout the League, the leaders of Saint-Malo took great in care in remaining masters of their own fate and developing their trade, by imposing a kind of trading market protected from the hazards of national politics. By remaining on the outskirts of the civil war, the Republic of Saint-Malo enabled the rise of a trading town.