The origins of Breton and oral tradition

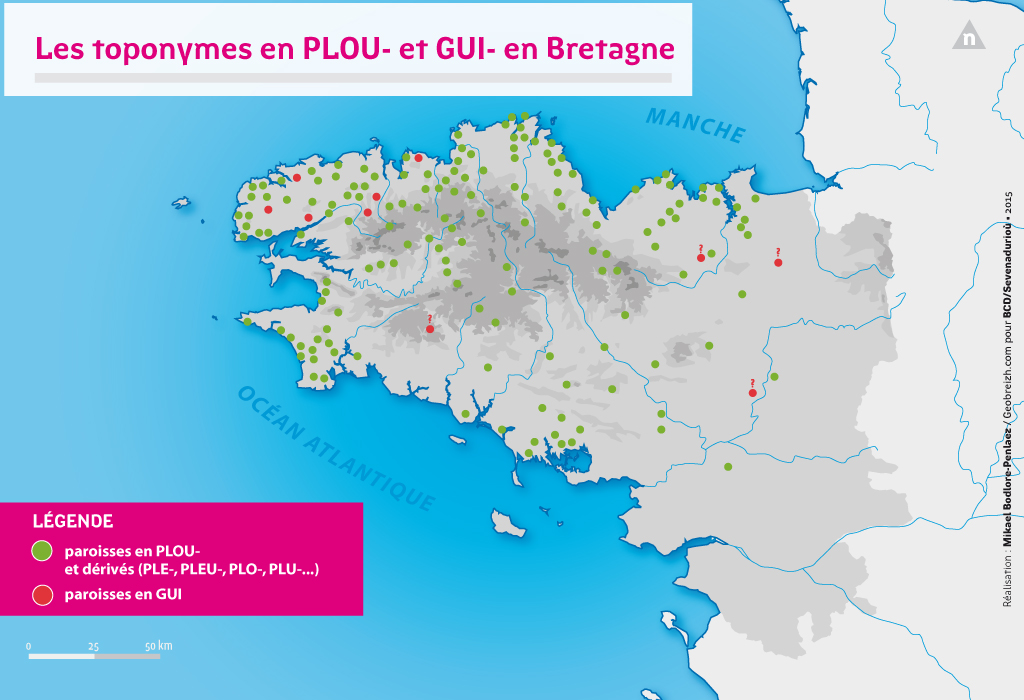

There is no information on the language(s) used in Armorica before the first protohistoric Celticization and the linguistic acculturation processes that followed, other than that a type of Gaulish was spoken at the time. The subsequent roman conquest (approx. -51 to 300AD) did not result in the Latinisation of the entire population as solely the administrative elite used Latin. The gradual decline of the Roman presence during the Later Roman Empire led to the arrival of auxiliary troops from Great Britain in the fifth century. A subsequent larger wave of emigration followed, over about two centuries, of some from the Island of Britain fleeing, amongst others, the Irish Scots. Armorica thus became Brittany. This Brythonic contribution mingled, to different extents with Gaulish according to the regions and the Breton language was born. From the X to the XII centuries, a section of the civil and religious elite who had fled Brittany during the Viking raids brought back linguistic traits from the Oil languages.

Traces of old Breton can be found in two ways: most frequently as glosses, in words annotated across Latin manuscripts as well as through certain anthroponyms and toponyms that are still present to this day and inform us about the territorial organisation of Brittany (Plou-, loc-,lan-, etc). Up until the XV century, we believe that Breton was probably spoken across the entire population; however, Breton, culturally, was not a written language. Indeed, no written narrative texts have been found, and the glosses in the manuscripts indicate the secondary nature of the Breton language in these domains. Latin was predominantly, and enduringly the language of cultural exchanges in Europe, and French was also rapidly adopted by the influential Breton political elite such as the dukes.

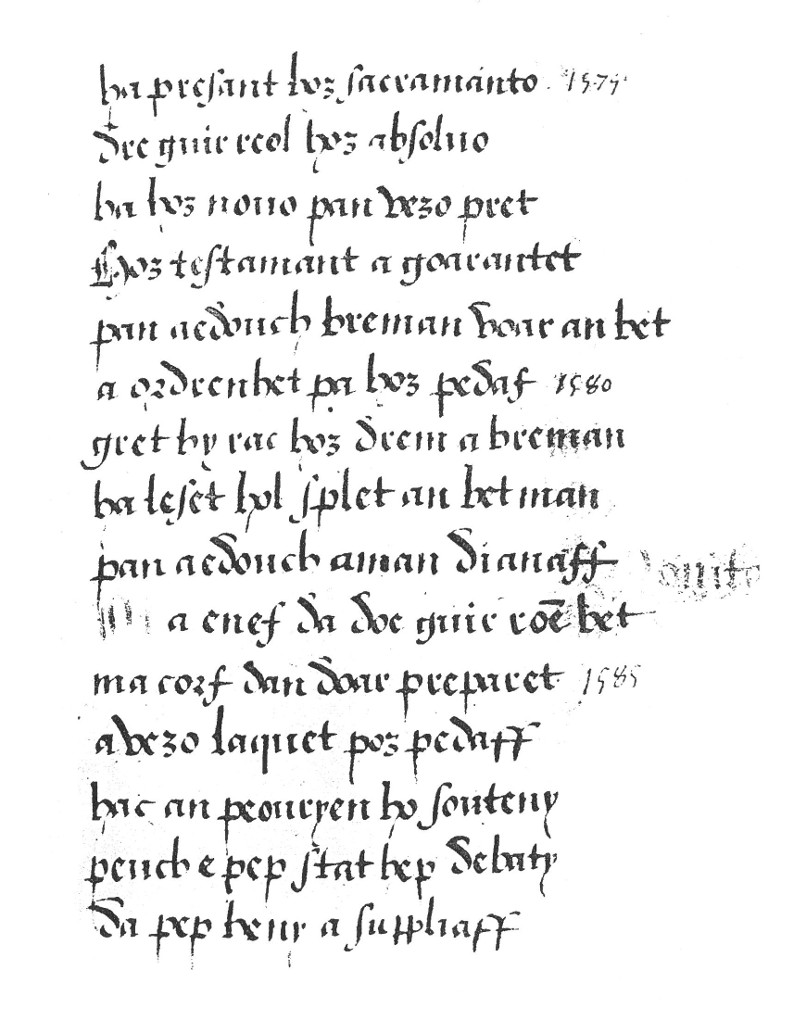

A written language: XV – XIX century

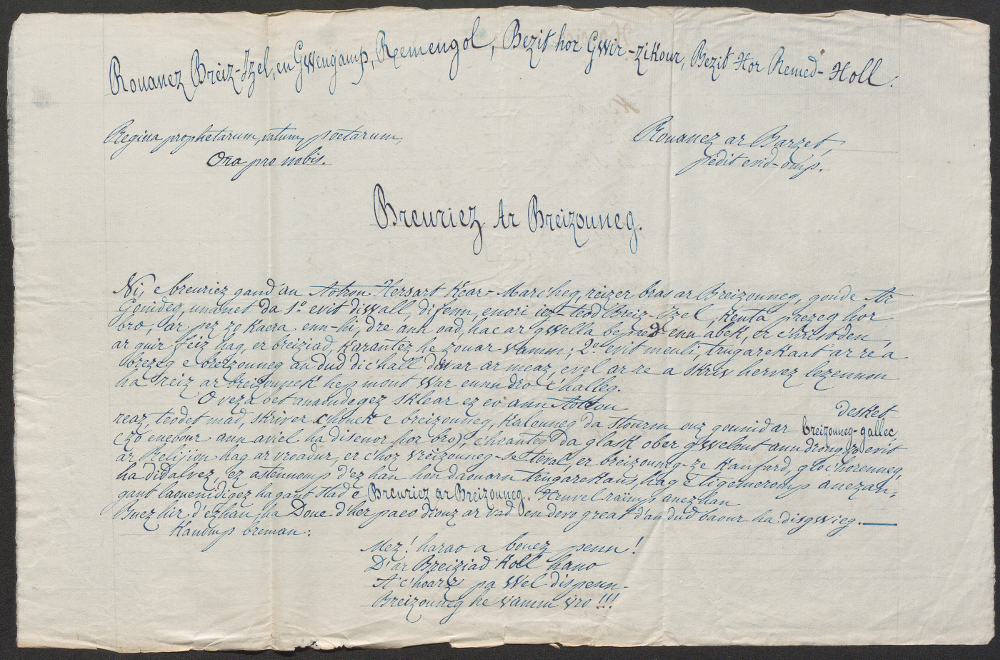

Breton language written practices emanated from religious purposes during the XV century in the form of remarkably complex verse structured mysteries and mystical poems that were inspired by the values and models conveyed by the church. Moreover, these texts reveal the sociolinguistic revolution of the time showing a cultural aspiration amongst a segment of the population that was gaining power: the urban bourgeoisie, particularly those living in ports who saw their economic power increase. Indeed, as they had not been trained in Latin or French, they turned to the catholic clergy (Mendicant Orders) to produce a Breton language literature.

Puis, lorsque cette bourgeoisie urbaine accède au français et au latin comme la noblesse urbaine dont le statut l’attire, cette pratique spécifique cesse progressivement. À partir des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, une nouvelle couche sociale voit son poids économique et son pouvoir social et politique croître : une aristocratie-paysanne (julots) alliée à la noblesse rurale. Ses aspirations culturelles se développent au croisement de sa formation classique dans les collèges jésuites (français, latin) et de sa volonté de médiation avec la population rurale bretonnante dont elle provient. C’est donc encore majoritairement le clergé catholique et ses relais biculturels qui tiennent les rênes de ce breton cultivé, même si quelques nobles ruraux cultivent un breton mondain à distance de ce cadre religieux et alors qu’apparaissent les premiers travaux lexicographiques. Les classes basses de la population – les plus nombreuses – parlent breton, sont très majoritairement analphabètes, mais ont accès à une partie de cette culture religieuse en breton par l’oral.

Subsequently, Breton written language practices progressively ceased as the urban bourgeoisie accessed French and Latin like the urban nobles whose status they wished to attain. From the XVII and XVIII centuries the economic, and social political power of a new social group increased: The rural aristocracy (named julots) who had strong ties and were associated with the rural nobility. The rural aristocrats aspired for cultural growth and were at the intersection of two worlds, being educated classically in the Jesuit colleges (French, Latin) but nonetheless, continuing to interact in Breton with the rural population from which they originated. Thus, primarily the catholic clergy and their bicultural representatives played the lead in this cultivated use of Breton even though some rural nobles also participated in this but outside the religious context and connotations thus, resulting in the first Breton lexicographical works. The lower strata of the population – the largest – spoke Breton but were predominantly illiterate and could only access some of the Breton-written religious culture orally.

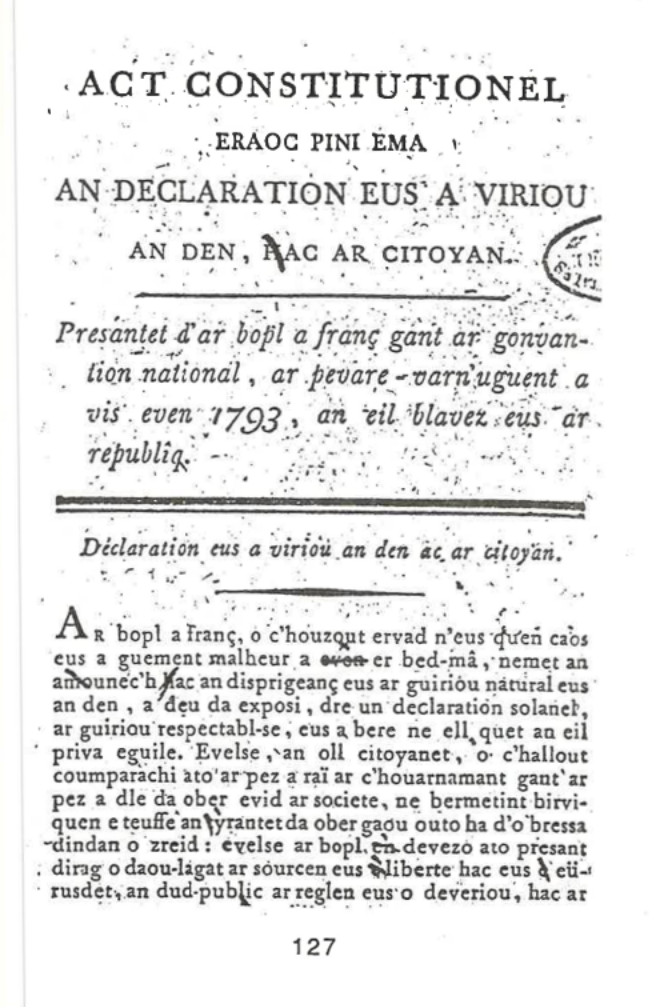

The French Revolution: The making of diglossia.

The context of the French revolution fluctuated between the promulgation of French citizenship, a desire for national unification and challenging the political enemies who had previously detained the power over culture and education. The Revolution marked a loss of opportunity to establish a Breton language culture that was not solely attached to religion. As soon as 1789 and in the following years, official revolutionary texts were translated into Breton, using the language as a political tool. However, the language was also controversial, and those opposed to the Breton language promptly took hold of the situation. The translation of texts in Breton mainly resulted from the intermediary rural faction of society who was bilingual. However, the radicalisation of the Revolution from 1791 produced the opposite effect to the previous movement and this intermediate faction of society became isolated from all political roles, thus slowly weakening the possible promulgation of the French revolutionary spirit through the medium of written Breton. Moreover, the closure of the Jesuit colleges restricted some of these young people from any intellectual training. Furthermore, opposition to the clergy's dominance in culture and education no longer involves the use of the citizens’ own language but rather a project of universal education and linguistic national unity to the detriment of regional languages.

By the end of the Revolution, some of the rural nobilities were no longer cultivated in Breton or even spoke it but had Latin and French classical training. The language function divide between French and Breton and the extinction of the previous bicultural social strata laid the grounds of the diglossia that was to come. This gradual language shift occurred in the XIX century with oral language practices (daily use and oral literature) continuing without significant changes until WWI. After some turmoil, cultural language written practices through Breton by the clergy became prominent again although French language practices became increasingly more common amongst the rural elites. Furthermore, a well-thought-through activist section who had acquired the language started to emerge amongst a tiny segment of the population who were attached to the language for various political reasons.

The XX Century: towards the end of heredity language practices.

During the XIX century, knowledge of French increased amongst the working classes due to the generalisation of formal education (in French), the increasing participation in the electoral and military institutions, the appeal of working in the civil service, etc. During the two world wars, the French language started to be used in the pulpit and for formal interactions. This diglossic situation tended to associate Breton to parity relationships (with close relations) and French for disparate relationships (with people we do not know). Moreover, these language practices were associated with social representations and sometimes considered as stigmatising:

- Rural versus urban

- Farmers versus town dwellers

- Old versus modern

- Private versus public

- Oral versus written

- Local versus universal.

During the 1950s-1970s, Breton-speaking adults ceased to transmit Breton to their children. The halt in the traditional family Breton language practice was due to the cumulative effect of these social representations, the development of formal education in rural secondary schools (boarding), the aspiration towards higher education, urbanisation and the rejection of traditional society, the significant growth of the media in France, etc. Furthermore, religious activities halted as a common community social practice, and the 1963 liturgic reform favoured the French language at the expense of Breton.

200 years of demands and activism

From the first third of the XIX century, like a mirror effect, the fall in the social use of Breton, on the one hand, led to a rise in demands in favour of Breton, on the other hand. These demands became significantly more prominent from the XX century and started to be endorsed by the state institutions in the XXI century. These include issues such as:

-

Language transmission: acquisition in school, intensive language courses, but also the media and, more recently, the reclaiming of the private sphere by encouraging family language practices, nurseries and holiday camps to use Breton.

-

Legitimisation: status planning (officiality, Chart in favour of minority languages) and corpus planning (linguistic normalisation, lexicographic works, literature and editing, translation prizes).

-

Visibility (signage and providing bilingual information, Breton as a symbolic token as well as for marketing purposes to promote businesses or Bretonhood (outside of solely western Brittany…).

The current situation is complex: Bretons declare to be overwhelmingly sympathetic towards Breton (heritage), but Breton speakers are often old (through grassroots hereditary practices) and numerically falling but demands in favour of the language are nonetheless increasing (new practices, at times ideological, at times symbolic).