It’s known as the Gwenn-ha-Du in Breton and the Bllan e Nair in Gallo, meaning White and Black in English. Some people believe it was held aloft victoriously after battles against the king of France. But at the risk of disappointing these romantic souls, it’s important to look at the facts. And the reality is there is nothing traditional about the Gwenn-ha-Du.

In fact it’s a pretty recent flag, created between 1923 and 1925. It was designed by a young architect from the town of Vitré called Morvan (Maurice) Marchal, who was an active member of the Emsav movement (pronounced Emzao), which campaigned for greater autonomy for the region, and even independence. Morvan Marchal was very committed to the cause. He joined a group of young artists known as the Seiz Breur (The Seven Brothers), many of whom were studying in Paris and were inspired by the idea of presenting a modern image of Brittany without straying too far from tradition. He was also the cofounder of the Groupe régionaliste Breton, a political movement that published the newspaper Breiz Atao ! (Brittany Forever!) which vowed “to reclaim the Breton fatherland”. With the same objective, Morvan Michel wanted to provide Brittany with a modern emblem, just as Finland, Catalonia and Ireland had done during the interwar period when the rise of nationalism across Europe had started to intensify.

Inspired by the United States

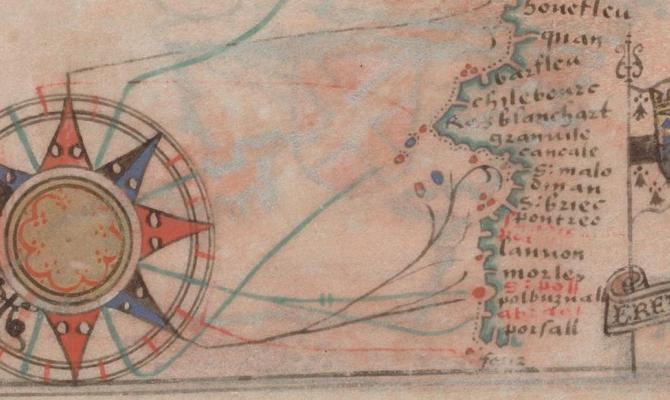

Morvan Marchal may have used Breton symbols that were characteristic of the Middle Ages (black and white, the ducal ermine), but its layout was inspired by the United States’ flag. To the left, the stars have been replaced by 11 ermine cantons. The four white stripes represent the four traditional dioceses of Lower Brittany: Léon, Cornouaille, Vannes and Trégor. The five black stripes represent the five traditional dioceses of Upper Brittany: Saint-Brieuc, Dol, Rennes, Saint-Malo and Nantes. In 1937, the Gwenn-ha-Du was chosen to represent Brittany as part of the Breton stand at the World Fair in Paris. However, the rise of Fascism in Europe did not spare the Breton region. Breton movements with affinities to Nazism, like the Parti national Breton, began to use the Gwenn-ha-Du. By the end of the Second Word War, it had become a reviled symbol used by collaborators.

Stadium splendour!

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the flag was revived once more, and that may well be down to the beautiful game. On 26th May 1965, Rennes was playing Sedan for the French Cup in Paris. Rennes won and there were celebrations across Brittany, but also on the streets of Paris where victorious supporters unfurled their flags. From then on, the Gwenn-ha-Du has been a constant presence in sports stadiums, as well as on the streets. In 1972 it featured alongside the red flags of the famous Joint français strike in St Brieuc. It also became omnipresent at every social and cultural event. Diwan, l’Amoco Cadiz, Plogoff… No protest was complete without the black and white banner. In the 1990s the aptly-named Raga Breizh, a student union linked to Brittany’s universities, gave it a new multicolour design. And certain Nantes football club supporters even redesigned it using the club’s colours, yellow and green.

Today, the Breton flag features on every license plate in Brittany. It may be young, but its future looks bright.

Translation: Tilly O’Neill